Some people who are infected with COVID-19 do not recover quickly. They live with the aftermath – long COVID – a multi-system condition that we must start learning how to manage, including pharmacists.

Long COVID, also known as post-COVID syndrome, describes lingering symptoms after the first acute infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Symptoms of the initial infection are now well understood: commonly fever and cough, sometimes sore throat, shortness of breath, fatigue, general aches and pains, headaches and either a runny or stuffy nose.1

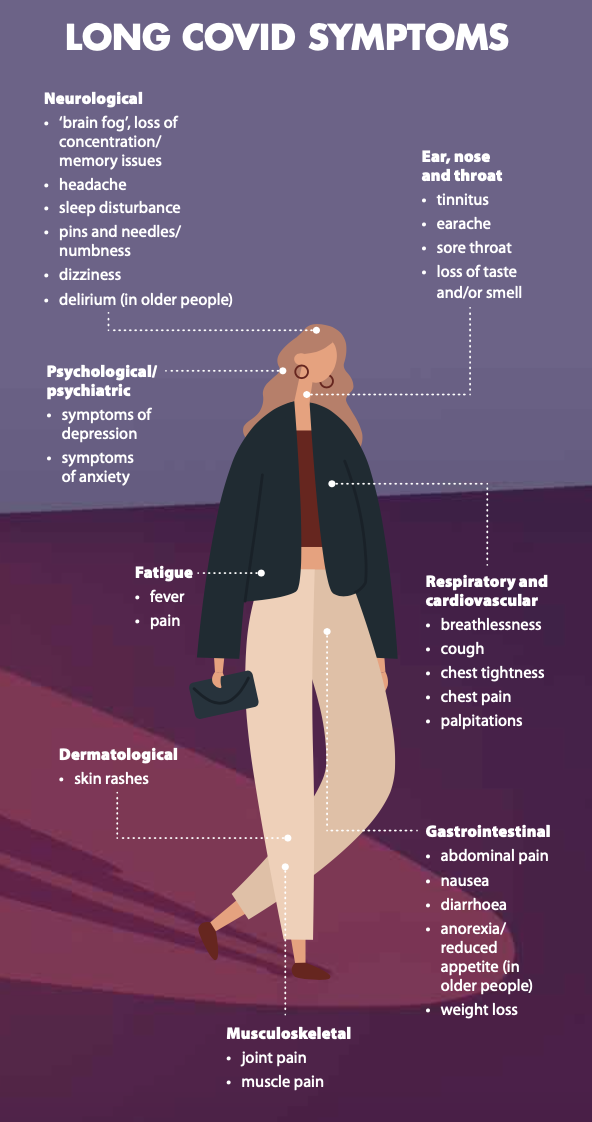

But long COVID has more than a dozen quite different symptoms lasting weeks or months after the infection has ended.2 Guidance on management of long COVID symptoms is in its infancy as patients navigate symptom management for however long symptoms persist. Some hospitals in Australia are starting to set up clinics that deal with long COVID patients. Primary healthcare providers, such as community pharmacists, can play a key role in identification and management of the constellation of symptoms that may present in patients with long COVID.

The World Health Organization recently developed a clinical case definition of post-COVID, with the understanding that it may change as new evidence emerges. The WHO definition states: ‘Post COVID-19 condition occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset of COVID-19 with symptoms and that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis … Symptoms may be new onset following initial recovery from an acute COVID-19 episode or persist from the initial illness.’3

Research to date offers a range of time frames to define long COVID. Most frequently it refers to symptoms continuing for more than 4 weeks. One recent study indicated that up to 30% of seriously ill patients reported at least one symptom, most commonly fatigue, persisting after 6 months.4 Ongoing symptoms can be more common in people who had more severe illness from COVID-19, for example in those who needed treatment in hospital.

Research to date

Recent Australian research5 looked at almost 3,000 people diagnosed in New South Wales between January and May 2020. The study, published in Lancet Regional Health earlier this year, indicates 80% of people infected with COVID-19 recover within 30 days, and symptoms in 96% had resolved at 120 days.

Lead author and University of New South Wales (UNSW) researcher Professor Bette Liu told Australian Pharmacist that the dominant symptoms in the cohort were fatigue and cough. She said most of the existing data refer to infections before the advent of the Delta variant and its devastating outbreaks in NSW and Victoria. Her group has plans to research long COVID after infection with the Delta strain.

‘[There are] not currently grounds to believe that the percentage of people diagnosed with long COVID after infection with the Delta strain will be greater than those diagnosed in 2020,’ Professor Liu says. ‘Although some studies suggest Delta could be more severe, so there is potential for more longer-term effects.’

A meta-analysis published in Nature Scientific Reports6 estimated the prevalence of 55 long-term effects of COVID-19 infection in more than 49,000 patients. Included studies defined long COVID as ranging from 14–110 days post-viral infection. An estimated 80% of infected patients developed one or more long-term symptoms. The five most common symptoms were fatigue (58%), headache (44%), attention disorder (27%), hair loss (25%), and dyspnea (24%).

Management of all these effects, the authors wrote, requires further understanding to design individualised interventions in post-COVID-19 clinics with multiple specialties.

‘From the clinical point of view, physicians should be aware of the symptoms, signs, and biomarkers present in patients previously affected by COVID-19 to promptly assess, identify and halt long COVID-19 progression, minimise the risk of chronic effects [and] help re-establish pre-COVID-19 health.’ The authors also drew attention to the parallel outcomes of other coronaviruses: ‘The results … are in line with the current scientific knowledge on other coronaviruses, such as those producing SARS and MERS, both sharing characteristics with COVID-19, including post symptoms.’

British immunologist Professor Danny Altmann has said evidence from multiple countries suggests that a significant number of people who contract COVID are at risk of developing longer-term illness. ‘[The] rule of thumb [is] that any case of COVID, whether it’s asymptomatic, mild, severe, or hospitalised, incurs a 10–20% risk of developing long COVID, and we haven’t seen any exceptions. There’s been quite a large standard deviation on LC [long COVID] estimates between studies,’ Professor Altmann, chair of immunology at Imperial College London, told AP.

‘That’s easy to understand when you consider both that studies are counting different symptom sets at varying time intervals from acute infection, and also that the equation has impact of people newly coming into the LC pool and some recovering. However, as the various meta-analyses show, there’s also striking convergence between observations in cohorts across the globe, whether in Wuhan or Scandinavia.’

Professor Altmann says it’s too soon to know if there are differences in long COVID after Delta. ‘It might be expected to be more a disease of young people, considering that demographics of the Delta wave are almost inverted relative to the first wave: fewer cases in the protected elderly and a huge burden in teens and 20s,’ he said. ‘Also, Delta does look a rather different infection, including some differential immunology.’

ADAPT study

Professor Gail Matthews, Head of Infectious Diseases at St Vincent’s Hospital and Head of the Therapeutic Vaccine and Research Program at the Kirby Institute at UNSW, is one of the chief investigators of the ADAPT study at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney.

It has been recruiting and following patients post-COVID since April 2020.7

ADAPT is a prospective cohort study that followed up all adults diagnosed with COVID-19 at St Vincent’s Hospital to characterise the effects of infection during the 12 months after diagnosis, by initial severity of COVID-19.

‘Duration of symptoms is often prolonged with a relapsing-remitting pattern to it,’ Prof Matthews tells AP.

‘In ADAPT, we showed that a similar proportion were still symptomatic at 8 months as at 3 months.’

In this cohort of 78 patients, the most common symptoms were fatigue, shortness of breath, chest heaviness or tightness, palpitations and brain fog.

‘By far the most common symptom is persistent, often severe fatigue,’ Prof Matthews says. ‘No single definitive treatment for long COVID exists, so symptom management and psychological support are valuable.

‘It is too early to understand whether long COVID will be different or more common after Delta infection,’ she says. ‘The ADAPT study is currently recruiting patients infected in the Delta wave and will look at this. To date, the only factors increasing the likelihood of long COVID are severity of initial illness and female sex.’

A glimmer of good news can be found in research by the Melbourne-based Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI), which found that long COVID-19 symptoms rarely persisted beyond 12 weeks in children and adolescents, unlike adults, with the Delta variant not significantly changing the risk for young people.8 However the authors, led by MCRI Professor Nigel Curtis, say more studies are needed to investigate the risk and impact of long COVID in young people to guide vaccine policy decisions.

At press time over 208,000 confirmed and probable cases had been recorded since infections began in Australia.9 From the UNSW research published so far, 8,320 people, representing about 4% of the total, would still have symptoms after 120 days.

Will, 24, lives with long COVID after infection in 2020 in America

The initial illness was incredibly frightening – the feeling of straining against your own body, trying to expand your lungs against this invisible force, struggling to breathe. But it was, in medical terms, a mild case. I wasn’t hospitalised. I was never in ICU and I was officially cleared after a couple of weeks. What a lot of people don’t realise is that even a mild case of COVID can turn into long COVID, which can severely impact your life for far longer than you would imagine. Long COVID is real. It’s random and characterised by periods of remission interspersed with intense symptom flare-ups. Months after my diagnosis I still couldn’t walk around the block without getting light-headed and needing to lie down, struggling to breathe. I was 23 and had just come off the back of 4 years of Division 1 college athletics, training 2–3 times a day, 6 days a week. Now I had such debilitating fatigue that I sometimes could not get out of bed. These days, a relapse can be brought on by something as simple as walking the dog. The physical impacts are lessening over time. I can now go through long stretches where I am mostly OK, but I’m still nowhere near normal. It’s the invisible impacts that mentally wear you down: the shame of having to tell people that you’re still not better yet; the frustration you feel with your own body; and the constant fear that at any moment the symptoms can come back. It doesn’t matter how young or fit you are. And it doesn’t matter how indestructible you feel. COVID can still hit you. And you don’t have to be on a ventilator to have your life turned upside down.’ * Will told his (edited) story at the Victorian Government daily media briefing on COVID-19 on 5 October |

More local long COVID research

Last month federal Health Minister Greg Hunt announced $900,000 in funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council Ideas Grant scheme to investigate the uptake and transport of the SARS- CoV-2 virus.

Led by Professor Frederic Meunier10 at the University of Queensland the grant is to understand the long-term consequences of potential virus interactions with brain cells and find ways to block infection.

Meanwhile, another UNSW psychology researcher and expert in HIV neuropsychology, Dr Lucette Cysique, has created an international taskforce of more than 120 members and developed neurocognitive testing recommendations12 that may help assess long COVID patients and which are being trialled in the ADAPT study. Recommended tests and questionnaires aimed at harmonising the assessment of patients were published recently11 in the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society and aim to explore whether abnormalities in the immune response to COVID-19 are driving the new syndrome.

Katherine Higgins MPSSouth Perth pharmacist Katherine Higgins MPS has a brother, aged 39, living with the debilitating symptoms of long COVID symptoms in London where daily cases of coronavirus have averaged up to 40,000 in recent months. Once employed by a leading global hedge fund, he had no co-morbidities when he caught COVID-19 in April 2020. His ‘symptoms were very mild’ but after several weeks ‘he began to experience a few residual respiratory symptoms like shortness of breath, exercise intolerance’, Ms Higgins relates. Fatigue, brain fog and some tinnitus in his ears were his main long COVID symptoms initially, and there was nowhere really to go, as health authorities scrambled to treat acute cases. Last month, Ms Higgins’ brother contemplated the probability of giving up his work in the hedge fund business. This was after researching his own pathways to health following suggestions for graded exercise and cognitive therapy from a long COVID clinic provided no relief from his Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, shortness of breath, fatigue, chronic brain fog, dizziness, vertigo and peripheral neuropathy. ‘For most of the chronic conditions we know of, we have a treatment or a plan or an idea of remission. These people don’t. They’re totally isolated,’ she says. As a health professional Ms Higgins advises her brother on drug interactions and adverse effects, but sees her greatest challenge as supporting his mental health. |

Monash University study

Last month, the first Australian study to examine the long-term impacts of COVID-19 – specifically in people who were in intensive care – was published in the journal Critical Care.12

Of the 212 critically ill patients studied in 30 Australian hospitals between March and October 2020, 43 died and more than 70% reported persistent symptoms 6 months after hospitalisation including fatigue, shortness of breath, low strength, headaches and loss of smell and taste.

Lead author Professor Carol Hodgson, an acute and critical care researcher at Monash University’s School of Public Health, has said around 40% could not perform their usual duties. With long and serious ongoing effects, more than a third of the group had new problems with mobility, more than 30% reported pain and cognitive impairment. Another 20% reported depression. She says the patient cohort had very little disability before contracting COVID-19.13

Ongoing problems with functioning could include physical functions such as the inability to walk for a kilometre, like beforehand, or stand for 30 minutes. ‘Or another one would be somebody who can no longer learn a new task … or they feel they’ve been so emotionally affected by their illness that it’s … a disability,’ Prof Hodgson says.13

United Kingdom experience

‘Long COVID is a new illness, which we are learning more about every day,’ state the educational materials for healthcare professionals by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), which has issued official ‘living’ guidance on best practice for ‘recognising, investigating and rehabilitating patients with long COVID’.13

One of its recommendations for self-management and supported self-management of patients in primary care and community settings suggests that it is ‘not known if over-the-counter vitamins and supplements are helpful, harmful or have no effect in the treatment of new or ongoing symptoms of COVID-19’.14

Another recommendation, in the ‘investigations and referral’ section, suggests urgent referral for people with ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 or post COVID syndrome for psychiatric assessment if they have severe psychiatric symptoms or are at risk of self-harm.

In June this year, the £100 million Long COVID Plan 21/22 was announced. It starts with this updated definition: The term ‘Long COVID’ includes both ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 (5–12 weeks after onset) and Post-COVID-19 Syndrome (12 weeks or more).

It has built on the five-point plan of October 2020 which funded research, established the NHS England Long COVID Taskforce and also offered specialist help at clinics across England where respiratory consultants, physiotherapists, other specialists and general practitioners helped assess, diagnose and treat those reporting symptoms of breathlessness, chronic fatigue, ‘brain fog’, anxiety and stress months after contracting the acute infection, whether or not they had been hospitalised or had a previous positive test. The long COVID clinics were to complement existing primary, community and rehabilitation care.

Kim Hanrahan, 49, from Newport, Melbourne, lives with long COVID

‘Last July [2020] my husband and I contracted COVID. Although Dave had asthma, he only [had] mild symptoms. A few days later I started to go downhill rapidly. By Day 11, I [was] bedridden, unable to sleep, with body aches and pains that not even strong pain relief could mask. I couldn’t finish a sentence without difficulty breathing. It was during my daily COVID call with DHHS [the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services] that I was unable to talk properly. I was advised to call an ambulance. I was taken to Footscray Hospital’s emergency department. I was put on oxygen and given fluids, steroids and medication. I went into ICU for 6 days, so lucky not to be on a ventilator. My lungs had collapsed, and I required a constant flow of oxygen. After a week in ICU, I spent a week isolated in a hospital room, as my blood oxygen was still very low. My husband was solely looking after [their twin boys, aged 9] in isolation, which took a toll on all of them. When I got home, I was still unwell and had to isolate. Recovery was slow. A couple of months after leaving hospital, unexpectedly, my hair started falling out. This temporary hair loss was due to the trauma on my body. Fourteen months later, I feel I have aged 10 years. My fitness has been severely impacted. I have brain fog at times and fatigue. I feel a lesser version of myself, which makes me sad for my boys. If I had got the Delta variant before vaccines were introduced, I truly don’t know if I would be standing here.’ * Kim Hanrahan told her (edited) story, at the Victorian Government daily media briefing on COVID-19 on 5 October. |

The role for primary care

As both a pharmacist and a sibling helping to support her brother’s mental health, Katherine Higgins sees her role as largely pastoral. ‘But what next?’ she asks.

‘This [current limbo] is next,’ she believes, for the hordes of Australian people who may shortly be in the same situation as her brother.

‘How do we help people when they come into the pharmacy with it?’ she asks. ‘We don’t know the long-term effects, and you can only hope that with the volume and number of people affected globally that something will come of it.’

Similarly, Kim Hanrahan, did have her own pharmacist who was great on delivery of medicines during her acute infection phase, but lacked answers once her long COVID emerged. Desperate for relief from her anxiety, fatigue and brain fog, Ms Hanrahan eventually asked all her own questions and dosed herself with pharmacy-bought vitamins B and D and magnesium to help her sleep.

Professor Hodgman says critically ill survivors of COVID-19 need to be directed quickly to general practitioners to be screened for new disability including physical, cognitive and psychological function. Any ongoing problems should be referred for further management including physiotherapy, speech therapy or a dietician in the case of swallowing difficulties or diet – just like rehabilitation.

‘And then the ones who have psychological problems with ongoing anxiety and depression, which is really common after COVID-19, might need referrals to psychologists,’ she says.13

Several Victorian hospitals now see patients in post-COVID clinics.

And last month, St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney was asked for approval for a new ‘Post-acute COVID clinic’ that would include long COVID patients, according to thoracic physician and UNSW researcher Associate Professor Anthony Byrne who has seen lung and cardiac impairment in his long COVID patients already. Pharmacists, he suggests, could help sleep-disturbed patients with advice on melatonin and services for mental health.

‘It’s a multi-system thing,’ he says of the significant long-term health ramifications of long COVID. GP and specialist referral ‘is key’ due to the respiratory and cardiovascular disease that may ensue. Shortness of breath, chronic cough and fatigue should all be referred for a specialist comprehensive assessment.

‘Because they we could say, “Is this a cognitive thing? Or is this a physical thing? Or are you fatigued because in fact you’ve got heart failure that’s unrecognised? Or are you fatigued because you’ve got severe sleep apnoea that’s unrecognised?”’

A/Prof Byrne said the proposed Post-acute COVID clinic would be staffed by respiratory and rehabilitation physicians to deal not only with pulmonary problems, but also noted muscular weaknesses, post-traumatic stress and psychological dysfunction. ‘It’s pretty much a multi- system disease’ and pharmacists, he says, could be of great help in identifying and referring patients.

While referral and supportive therapy are initial roles for pharmacists now, as knowledge grows on treatments, disease progression and recovery, this is likely to change.

Pharmacists across hospitals, community practice and general practice will need to stay across the emerging evidence to ensure support for patients in their challenging recovery phase.

Read AP‘s full interview with A/Prof Byrne here.

References

- Australian Government, Department of Health. COVID-19: identifying the symptoms. 2020. At: health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/10/coronavirus-covid- 19-identifying-the-symptoms_2.pdf

- Long-term effects of coronavirus (long COVID). 2021. At: https://bit.ly/3obq4tc

- World Health Organization. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus, 6 October 2021. At: www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1

- Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ ,et al. Sequelae in Adults at 6 Months After COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(2):e210830.

- Liu B, Jayasundara D, Pye V, et al. Whole of population-based cohort study of recovery time from COVID-19 in New South Wales Australia. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021;12:100193. Epub 2021 Jun 25.

- Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2021;11:161447.

- Darley DR, Dore GJ, Cysique L, et al. High rate of persistent symptoms up to 4 months after community and hospital-managed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Med J Aust 2021;214(6):279–80.

- Media release: Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI). 2021. Long COVID symptoms in children rarely persist beyond 12 weeks. At: www.scimex.org/newsfeed/long-covid-symptoms-in-children-rarely-persist- beyond-12-weeks99

- Australian Government Department of Health. Coronavirus (COVID-19) case numbers and statistics. [date of press 26/11] 2021. At: https://bitly/3wtpMld

- Ministers, Department of Health. Media. $239 million for Australian health and medical researchers. 2021. At: https://bit.ly/3EXIRid

- Nazaroff D. Long COVID ‘brain fog’: neurocognitive tests to harmonise global methods. UNSW Sydney Newsroom 2021. At: https://bit.ly/3H2XHpD

- Hodgson CL, Higgins AM, Bailey MJ, et al. The impact of COVID-19 critical illness on new disability, functional outcomes and return to work at 6 months: a prospective cohort study. Critical Care 2021. Epub 2021 Nov 8.

- Monash University. LENS. Not getting over it: the long, rocky road to recovery from COVID-19. 2021. At: https://bit.ly/3nqfcbK

- Post-COVID Syndrome (Long COVID). 2021. At: www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/post-covid-syndrome-long-covid/

- COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. At: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

‘I contracted COVID in March [2020], 3 days after returning home from Boston, where I had been studying. I’ve been battling long COVID ever since.

‘I contracted COVID in March [2020], 3 days after returning home from Boston, where I had been studying. I’ve been battling long COVID ever since.