The Urinary Tract Infection Pharmacy Pilot – Queensland (UTIPP-Q) linked increased access to healthcare with reduced rates of hospitalisation while factoring in antimicrobial stewardship. Its success is a stepping stone towards wider pharmacist prescribing.

UTIs are a common healthcare issue that can lead to wider consequences, said Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Professor Lisa Nissen FPS, who led the 18-month pilot and presented a session on its outcomes at PSA22.

‘There is a significant rate of hospitalisation for people presenting with UTIs – often because the symptoms come on fairly quickly,’ she said.

‘They can happen after hours, [with] people having difficulty getting medical services, access to general practice or any kind of care.’

This was a key driver behind Queensland Health’s move to trial treatment for uncomplicated UTIs in community pharmacies. QUT won the government tender to provide training to community pharmacists.

‘Making things available in the community for people lessens the burden on part of the system,’ Prof Nissen said. ‘They were interested in knowing where pharmacists could play a role.’

UTIPP-Q treatment guidelines

When patients presented to a participating pharmacy with symptoms of a UTI, pharmacists completed a screening process that excluded several groups, including men, patients with allergies, or those with a history of catheter use or kidney stones.

Pregnant patients or people outside the 18–65 year age range were also excluded, along with people who had symptoms of thrush or a sexually transmitted infection, as well as those with symptoms of a complicated UTI.

Eligible patients were treated in accordance with the PSA Treatment guideline for pharmacists: cystitis using a stepped approach.

‘First-line treatment is a 3-day course of trimethoprim, then stepping into nitrofurantoin if that’s not effective or they can’t use trimethoprim – and then [cefalexin],’ Prof Nissen said.

Most patients (92.6%) were treated with trimethoprim, demonstrating that the pilot adhered to antimicrobial stewardship.

‘It’s about using the most appropriate treatment where possible for the shortest period of time, targeting the most appropriate organism,’ she said.

‘If it wasn’t working [we were] referring people on to another practitioner for further review.’

A steady service

There were 820 pharmacies enrolled in the pilot, but not all of them engaged in the service.

‘There were [several] pharmacies that didn’t do any, a number that did 0–20, some that did a moderate number and a few that did a lot,’ Prof Nissen said.

‘The pharmacies that did a number of UTI services over the course of the pilot, at the most would have done one script a day.’

Some recent media coverage of UTIPP–Q described pharmacists as ‘out of control with our antibiotic prescribing’ and ‘using it for pecuniary interests’.

But PSA strongly rejected criticism of pharmacists’ ability to provide the service.

‘Pharmacists are registered health professionals with the same ethical and moral obligations as doctors,’ said PSA National President Dr Fei Sim.

‘Community pharmacies are not “unsupervised retail settings” – they are primary healthcare destinations, as well as the most accessible healthcare setting in Australia.

‘Pharmacists undergo a minimum of 5-years’ training, as well as additional education and training for this very trial, so that they can provide the best possible care to their patients.’

Follow-up care

GP groups have also claimed that patients were lost in follow-up, despite pilot protocol requiring pharmacists to make three attempts to follow-up within 7 days of starting treatment.

‘Out of 6,751 people, we managed to get follow-up for 2,409 people (36%), which from a research point of view gives us a good cohort of folks to understand what happened afterwards,’ Prof Nissen said.

‘We can launch learnings from these pilots to grow what we do in the profession.’

professor Lisa Nissen fPS

There was no discernible difference between those who were reached for follow-up and those who weren’t, with no missing groups identified in terms of age, location or symptom presentation.

What the researchers could discern from follow-up patients is that dysuria, urinary frequency and urinary urgency were the most common symptoms.

‘That met the protocol for what we expected people would have in empiric treatment for UTIs [because] we weren’t doing urine testing,’ Prof Nissen added.

Most patients (87%) reported a resolution of symptoms following treatment. Some whose symptoms had not resolved needed to seek follow-up care (7.6%). But Prof Nissen said a 10% failure rate on a 3-day course of trimethoprim was standard.

There were also four people who presented to emergency departments (ED), which included only two patients with unresolved symptoms, one with an allergy and a patient with appendicitis.

‘We had clinicians review the admissions of people who presented to ED … [who] looked at the treatment from the pharmacist for the presenting symptoms related to the protocol, and if [it] was appropriate or not,’ Prof Nissen said.

‘Particularly with the appendicitis case, they had the view that the appendicitis was unrelated to the UTI presentation.’

Looking forward

Despite concern from doctors about the extension of the pilot, Prof Nissen said the Queensland Government’s decision to make it a part of ongoing practice is a crucial vote of confidence in pharmacists.

‘The key findings [reinforced] that it was safe and appropriate, and pharmacists did use the protocols and make good choices,’ she said.

The UTIPP-Q led to recognition of pharmacists’ expertise in recommending medicines using different models of prescribing, and has supported the necessary regulatory changes to ensure greater access to treatment in pharmacies.

Prof Nissen said that if scope of practice and competencies are reviewed, there could be great opportunities for pharmacists to provide services and take accountability for their care.

‘We can launch learnings from these pilots to grow what we do in the profession,’ she said.

Vaccination is the perfect example of what was once a niche pharmacy practice becoming mainstream after its effectiveness was demonstrated.

‘Now students graduate able to vaccinate, and during the pandemic we used students as vaccinators under the supervision of pharmacists,’ Prof Nissen said. ‘Eventually, over time, these things roll into just being practice.’

Prof Nissen explained how pharmacy services can be further leveraged to expand practice, such as building on vaccinations to provide injectable medicines.

‘We uplift on the understanding of the background medicine, but we use the skill to administer what we’ve learned from doing vaccination to crack on with something else,’ she said. ‘It’s building and growing on things that we’re doing each time.’

As the pilot lead for UTIPP–Q, Prof Nissen said she felt like a ‘human shield’ constantly under fire. But she believes it was ‘absolutely the right thing’.

‘It is the crack in the wall that we have to run right through, because we have the skills. If we are not where medicines are, who will be?’ she asked.

‘Get on board [with] any pilot. The government wants you, patients need you. Just do it.’

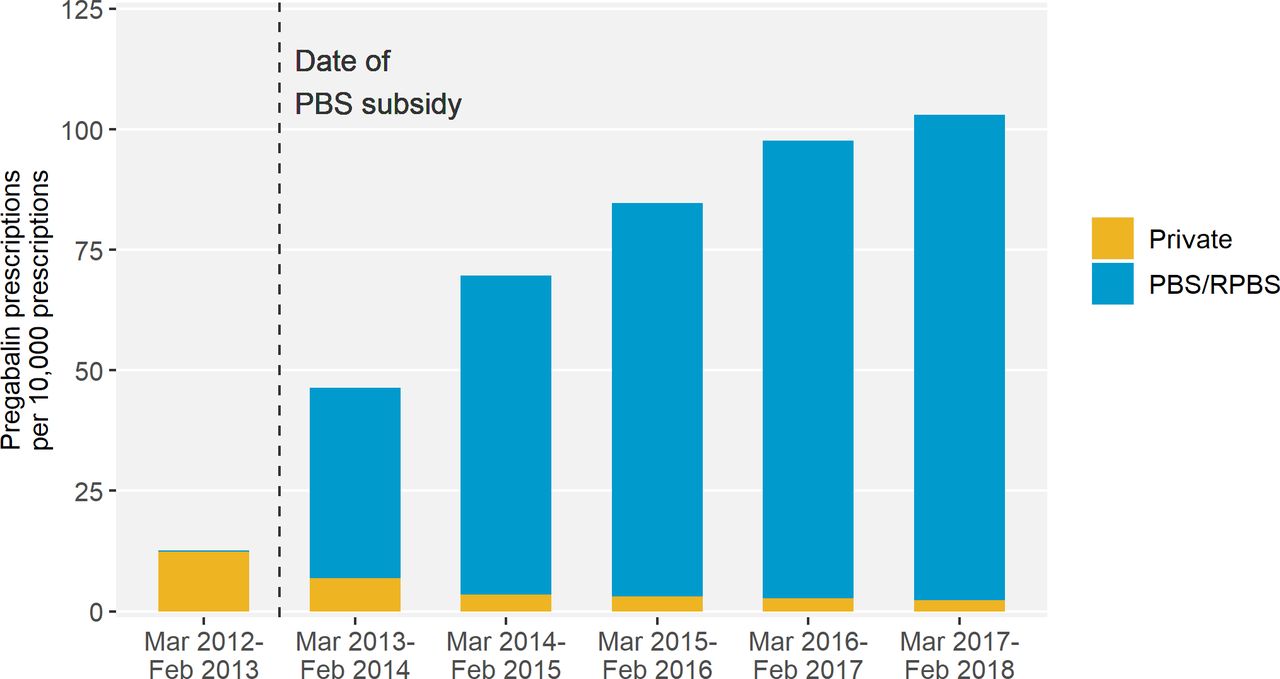

Source – Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012–2018: a cross-sectional study[/caption]

Source – Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012–2018: a cross-sectional study[/caption]

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]