A joint survey by PSA, the Pharmacy Guild and the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia conducted over April–May 2021 found that medicine shortages are having a dire impact on patients and pharmacists.

Almost all (98%) pharmacists surveyed said they had experienced a medicine shortage in the previous 7 days, with an average of 30 medicines in low supply.

An average of 5 hours of pharmacist time and 4.5 hours of non-pharmacist time per week was dedicated to solving medicine supply issues.

Of the 136 medicines identified to be in short supply, 71% were reported on the Therapeutic Goods Administration’s (TGA) medicine shortage reports database. However, 86% of pharmacists indicated that the situation had not improved over a 12-month period.

Caroline Diamantis MPS, a community pharmacist and PSA Board Director based in the inner-west Sydney suburb of Balmain, said pharmacists have been scrambling to find medicines for urgent cases and were keeping waiting lists for others.

‘A lot of them are life-saving medications that keep [patients] living a normal healthy life,’ she said. ‘You can’t help but feel empathetic and try to explain that we’re not responsible.’

Ms Diamantis is frustrated that the onus is once again on pharmacists to adapt their workflow to manage the situation.

‘If stock dribbles in, we have new processes in place and staff members are assigned to go through waiting lists to contact patients,’ she said.

Brisbane-based pharmacist Tamara Smith MPS, said continuation of therapy is the most important thing for patients, so her team is ‘banding together to find solutions’.

‘We’re calling patients’ regular GPs to discuss potential changes to therapy or other local pharmacies to see who might have stock to continue their current therapy,’ she said. ‘But [for] some patients we just aren’t able to find a solution in time for their next dose.’

Semaglutide stress

For both pharmacists, the shortage of semaglutide injections (Ozempic) has been the toughest to manage.

Explaining to weight-loss patients that the medicine is prioritised for patients with diabetes is often an uncomfortable conversation, Ms Diamantis said.

‘We’ve been asked by the government to prioritise people with diabetes, but then we have to [relay] that message to [weight-loss patients] who consider their obesity impactful on their health and wellbeing.’

In some cases, pharmacists have to find alternative solutions.

‘We have to call GPs to try and swap them to a different medication, or refer them back to their endocrinologist,’ Ms Smith said.

Before Ozempic came onto the market, most of Ms Smith’s patients were on their previous medicine long term, making the idea of another switch even more stressful.

When the pharmacy didn’t have Ozempic in stock for over a month, one of her dose administration aid (DAA) patients was particularly concerned about ceasing therapy.

‘It was the only [therapy] the patient had been stabilised on, so they were concerned their diabetes would again become uncontrolled without access to Ozempic,’ she said.

Ms Smith reassured the patient that she was able to help and reached out to the prescriber.

‘The GP changed their therapy to [dulaglutide], which was available at the time. With the patient unable to travel elsewhere to source medication, we’ve kept stock levels on [dulaglutide] for that patient, so we’re in the safe zone over the next few months,’ she said. ‘The patient was really appreciative.’

Antibiotics and over-the-counter medicines

Some commonly prescribed antibiotics that don’t have ready alternatives are regularly out of stock, Ms Diamantis said, including metronidazole and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid.

‘These are urgent cases where people have an acute infection and they require treatment immediately. It’s not a waiting list scenario.’

For one patient who was prescribed amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875mg/125 mg, Ms Diamantis worked with the prescriber to alter the dosage.

With that strength of the medicine out of stock, the patient was instead prescribed an increased dose of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 500mg/125 mg.

‘This patient, who had a severe bronchial infection, was desperately in need of something stronger than amoxicillin,’ she said. ‘It wasn’t an exact match, but the patient was able to get both of those ingredients into their system.’

With many everyday over-the-counter medicines also out of stock, Ms Smith looks for alternative medicines in supply.

‘If stock dribbles in, we have new processes in place and staff members are assigned to go through waiting lists to contact patients.’

caroline diamantis MPS

‘A lot of the cold and flu phenylephrine products are unavailable. Decongestant nasal sprays are [also] hard to source from many suppliers,’ she said.

‘So, we try to find another appropriate therapy such as pseudoephedrine, which at the moment is a little bit easier to source.’

Before supplying alternative medicines, Ms Smith ensures they are appropriate for the patient. If not, patients are referred to another pharmacy or to their GP.

Working with GPs

In Ms Diamantis’ experience, GPs are not aware of medicines that are out of stock unless patients or pharmacists inform them.

Most doctors will work with pharmacists to find a solution.

‘Both of us will be on MIMS looking up an [appropriate] alternative,’ she said.

‘There have been times where specific contraceptive pills have been unavailable, and the doctors are happy for us to help them look for a substitute.’

When Ms Smith has to go through ‘gatekeeper upon gatekeeper’ to reach a prescriber, and the patient is unable to make an appointment within a suitable timeframe, she makes it clear to the medical practice that if she can’t reach the prescriber, it will be the patient who is impacted.

‘That works most of the time,’ she said. ‘But I have had to fight for my patients at times.’

Other strategies for managing low stock

To ensure patients get access to their medicines, Ms Smith’s team tries to balance supplies of medicines going out of stock with monthly demand.

‘As soon as [patients] present with a script, we find out how much medication they’ve got left, whether they can see [the prescriber] before that medication runs out, and if not call the [prescriber] to find a solution.’

Ms Diamantis said spending more time sourcing medicines from suppliers has become a part of everyday workflow.

‘We use three suppliers, and we spend a significant part of every day logging into the ordering portals to determine who has what stock and what strength,’ she said.

Ms Diamantis also ensures patients who need their medicines most have access to them, including DAA patients.

To facilitate this, pharmacy assistants keep an eye on what medicines are in short supply with wholesalers.

‘Some of our generic suppliers forward us [lists] of potential short stocks,’ she said.

‘We look at those lists and try to calculate who’s on those medicines in the [DAA] program.’

What would help

The report made three key recommendations to improve the situation:

- the TGA’s medicine shortage reports database should accurately reflect the medicines available for purchase through wholesaler ordering portals

- the government should engage with pharmacy organisations to improve the management and coordination of medicine shortages

- medicine manufacturers should improve the quality of information communicated to pharmacists, prescribers and patients about medicine shortages.

Similar to when certain strengths of Estradot patches were in short supply 2 years ago, Ms Diamantis thinks arrangements should be put in place for pharmacists to substitute medicines.

‘It would be amazing if we could have autonomy to swap strengths,’ she said.

Late last year, for example, she only had access to atorvastatin 20 mg, so patients prescribed the higher strength (40 mg) were advised to double their dose.

‘I still legally had to request permission from the doctor to do that,’ she said. ‘If we had a standing rule allowing us to make these changes if it had the same clinical effect, it would [save] the hassle of contacting doctors and wasting everyone’s time.’

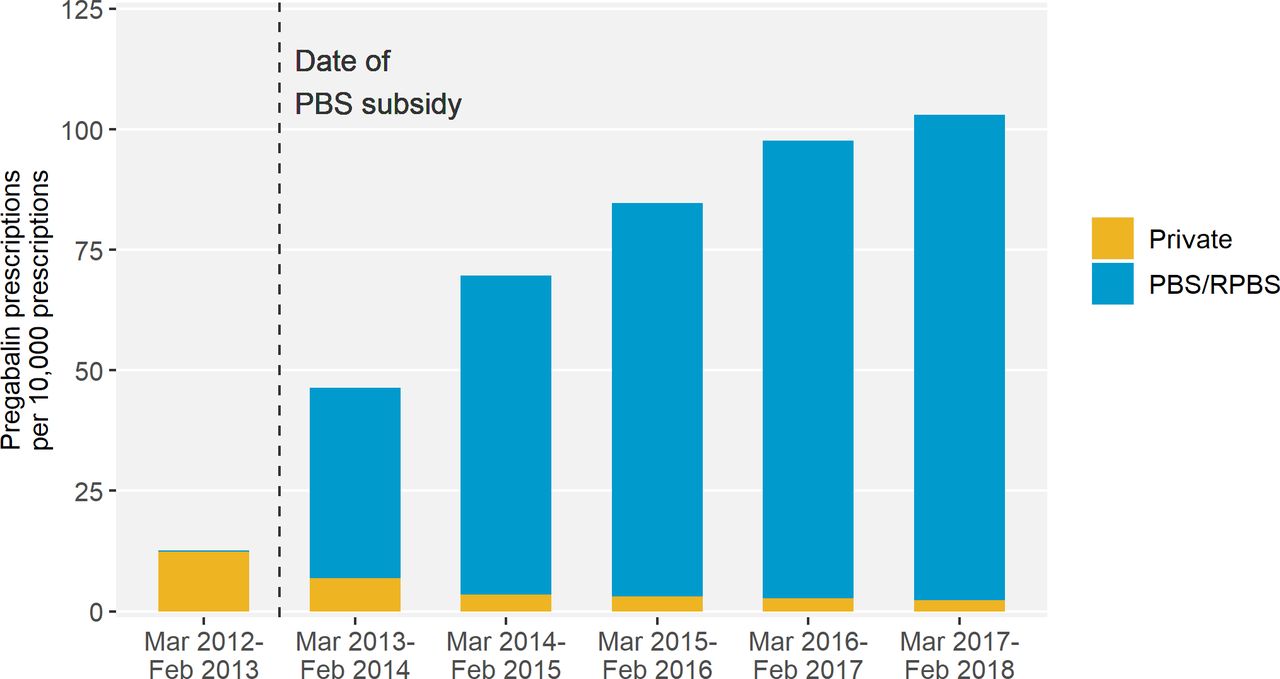

Source – Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012–2018: a cross-sectional study[/caption]

Source – Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012–2018: a cross-sectional study[/caption]

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]