The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care Commission’s AURA 2023: Fifth Australian report on antimicrobial use and resistance in human health found that after a sharp reduction in 2020-21, antimicrobial prescribing has again surged.

To mark World AMR Awareness Week (18–24 November 2023) Australian Pharmacist sat down with the Commission’s Senior Medical Advisor Professor John Turnidge AO for a Q&A session on new patterns of antimicrobial resistance and what pharmacists can do to help.

AP: What are the key trends in antibiotic use highlighted in the report?

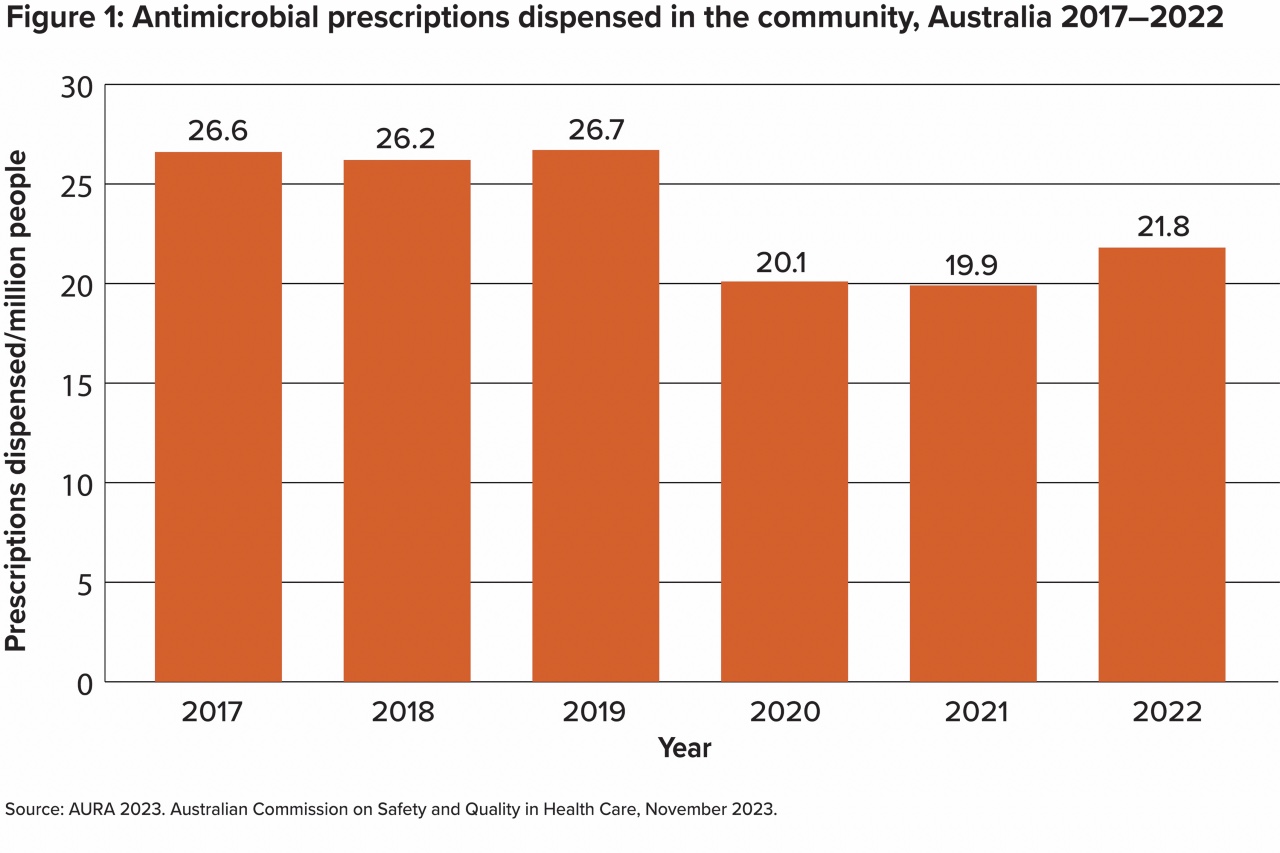

Prof. Turnidge: The most interesting trend was the rapid decline in antimicrobial Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) dispensings in 2020 and 2021.

COVID-19 lockdown measures, border closures, reduced access to GPs and the sudden drop in the number of circulating respiratory tract infections all played a role in that reduction.

There was a significant drop in prescribing of antibiotics for respiratory tract infections in 2020-21. However, there has been an uptick in antibiotic prescribing in 2022 – with a 10% increase over the previous 2 years.

Antibiotic prescribing is yet to reach the levels of 2019. We’ve never had a national campaign to help prevent a relapse in antibiotic prescribing – it would be helpful to ensure both prescribers and patients understand that antibiotics should only be used in very specific circumstances.

2022 highlights

Hospitals, the community and aged care

|

AP: Which bugs are increasingly resistant to antibiotics?

Prof. Turnidge: It’s the common garden bugs such as Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (N. gonorrhoeae) that worry us the most.

Multidrug resistance to E coli, which is the leading cause of septicemia, has become increasingly common. There has also been resistance detected to our reserve antibiotics.

There’s also been a shift in Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains. Over the last few decades, the community strains have become dominant and the hospital strains have faded into the background.

Now, if people get MRSA in hospital, it might very well be from a strain they were already carrying.

At least 20% of golden staph are now MRSA, which further complicates things.

The ideal staph treatments are complicated, expensive and usually intravenous. The more these classes of antibiotics are used, the greater the risk of increasing resistance to those treatments.

One thing we know about antimicrobial resistance is that it’s inevitable. If we use antibiotics, we will lose them. The key strategy is to reduce and restrain antibiotic use.

AP: What can pharmacists do to support further improvement in antibiotic use in primary care?

Prof. Turnidge: There has been a gradual increase in private prescriptions for antibiotics. While this may be partly designed as a cost-saving measure, it’s actually a perverse incentive.

When we started the AURA surveillance 7 years ago, there was a treasure trove of data from the PBS giving us direct understanding of what was happening in the community which we can’t afford to lose.

Community pharmacists could ensure dosages on antibiotics on scripts align with Therapeutic Guidelines.

Community pharmacists could ensure dosages on antibiotics on scripts align with Therapeutic Guidelines.

But an important first step is to establish a formal dialogue between GPs and pharmacists through local area health networks. They need to be able to sit around the same table and say, ‘These are the issues. How can we tackle antimicrobial stewardship together?

AP: What needs to happen in the diagnostic space?

Prof. Turnidge: Instant diagnostics would have a big impact on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. Patients need to be able to turn up to the doctor with a sore throat and work out whether they have a bacterial or viral infection on the spot.

If it turns out the patient has a virus, isn’t prescribed antibiotics and just receives symptomatic treatment – that would be transformative.

AP: Why is aged care an area of concern and how can pharmacists promote antimicrobial stewardship?

Prof. Turnidge: Residential Aged Care Facilities are recognised as a major reservoir for antimicrobial misuse and multi-resistant bugs.

Because residents are often in and out of hospital, they’ve also likely had multiple exposures to antibiotics in the past.

It’s important to get people used to the idea that you do not treat asymptomatic bacteriuria. Once people are over 70 years of age, a significant proportion will carry bugs in their urine. While a dipstick test may indicate a positive Urinary Tract Infection (UTI), they often have no symptoms whatsoever.

All the evidence suggests that when patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria are treated with an antibiotic, they can relapse with a symptomatic UTI.

The Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission and the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care are working on models to regularise the use of antimicrobials in the aged care sector. That will mean that pharmacists are more prominent in aged care units than they have been in the past.

For now, pharmacists embedded in RACFs should engage in deep and meaningful conversations with nurses about inappropriate antibiotic prescribing.

Historically, we understand it’s nurses who often make decisions around antibiotic prescribing for positive dipstick tests, for example. Pharmacists can help to address those types of mythologies that are causing more harm than good.

AP: How can hospital pharmacists help to ensure appropriate prescribing for surgical prophylaxis?

Prof. Turnidge: The evidence base for surgical prophylaxis is restricted to a certain number of surgeries, including joint replacements, large bowel operations or major cardiac surgeries.

While the choice of antibiotics is usually correct, the timing can be wrong. One dose is sufficient in most cases, and the longest duration should be 24 hours.

However, what often happens is the surgeon decides to lengthen the duration of therapy ‘just in case’.

Pharmacists in antibiotic stewardship roles should help to ensure antibiotic prophylaxis is restricted to the surgeries where it does have an impact, and embed the mantra of the ‘right dose, right drug, right duration’.

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]