Measles cases are skyrocketing worldwide. Despite being declared ‘measles free’ since 2014, more than 28 cases of measles have been recorded in Australia this year, including recent alerts in Sydney and South Australia.

This is more than the number of cases recorded in 2023 all together. Is this just a reality of more overseas-acquired cases following increases in overseas travel, or is Australia’s measles-free status at risk?

Professor Margie Danchin, group leader of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute’s Vaccine Uptake Group, shares seven things pharmacists need to know about measles.

About our expert

|

1. Childhood vaccination rates are falling

Pre-pandemic, measles, mumps rubella (MMR) vaccination coverage in children at 2 years of age sat between 92–93% – both locally and nationally, said Prof Danchin.

However, coverage has now slipped below 90% in many areas, particularly in the North Coast region of New South Wales, where the childhood vaccination rate at 2 years of age was 86.7% in 2023, said Prof Danchin.

‘To prevent outbreaks of measles, we need coverage of about 95% for two doses,’ she said. ‘In regions where coverage drops well below that rate, there’s not enough community immunity to prevent an outbreak.’

2. We don’t know why vaccination rates are dropping

Low measles vaccination rates can be found at both ends of the socio-economic spectrum due to acceptance and access barriers.

It’s been over a quarter of a century since the widely refuted publication of the report linking the MMR vaccine to autism in the Lancet. While belief in this link has receded in public consciousness, it’s still present in some pockets in the community, including among higher socio-economic groups.

‘We’ve done research that found up to 10% of parents still believe that the MMR vaccine can cause autism,’ she said.

Among lower socio-economic groups, a range of practical barriers can get in the way of vaccination.

‘You need two doses of MMR, one at 12 months and one at 18 months,’ said Prof Danchin.

‘For some families vaccination is not a priority, or they may have forgotten their child is due for their vaccination.

‘They may also not be able to get to the GP due to a number of access barriers such as work, difficulty arranging care for other children, or the cost of transport.’

However, Prof Danchin cautions against assumptions. ‘It’s dangerous to assume we understand why MMR coverage might have fallen.’

3. Australia will experience a measles outbreak that could prove fatal for some

Of all the vaccine preventable diseases, measles is the most infectious. To put it into perspective, the reproductive number (R0) for COVID-19 was between 1–2, whereas the number of secondary cases from a primary case of measles is 12–18, said Prof Danchin.

‘To prevent outbreaks of measles, we need coverage of about 95% for two doses.’

Professor margie danchin

With the borders now open, international travel resumed, and a dramatic increase in measles cases globally – the biggest outbreak risk is the importation of measles cases from travellers into Australia.

‘Outbreaks are coming, we will see them this year,’ she said. ‘We know coverage is low in many regions, so it’s only a matter of time.’

Along with being highly infectious, measles also has a significant morbidity rate in children under 5 years and older adults. About 1 in a 1000 people or 0.1% will die from measles.

‘It can cause inflammation of the brain, seizures, and respiratory complications such as pneumonia,’ said Prof Danchin.

If pregnant women contract measles, babies can be born prematurely or have low birth weight. However, because MMR is a live vaccine, it cannot be administered in pregnancy.

‘Women contemplating pregnancy, travel, or both need to think about their MMR status before they get pregnant,’ she said.

4. Catch-up vaccination is for adults, too

Post 1996, when people were able to readily access two free doses of the MMR vaccine, there was less natural exposure to measles in the community.

‘A lot of adults haven’t had two doses after that time, so they are not immune to measles,’ said Prof Danchin.

‘These patients could get serological tests to see if they are immune to measles but it’s far better to get an MMR vaccine if they believe they haven’t had both doses.’

Pharmacists can also provide catch-vaccinations to children aged 5 years and over– particularly to those who missed out during COVID-19.

‘If the 18-month MMR dose is missed, a single catch-up vaccination can be administered at any time,’ she said.

Because pharmacists are so accessible, they are an important vaccinating workforce for helping parents overcome practical barriers to vaccination.

‘Pharmacists can say, “I’m open late, you can bring your children in after work tomorrow night”,’ said Prof Danchin.

5. Pharmacists should focus on travel vaccination

As Australians gear up to travel overseas during the European summer, where there’s been a 30-fold increase in measles cases, the importance of vaccination should be emphasised. But it’s not just Europe that travellers need to worry about – measles cases have been recorded across the Asia Pacific region, said Prof Danchin.

‘Outbreaks are coming, we will see them this year.We know coverage is low in many regions, so it’s only a matter of time.’

Professor margie danchin

‘If pharmacists are aware an adult is travelling, they should ask about polio, measles, and whooping cough vaccination,’ she said.

‘Parents might also come in for some travel medicine or talk about travel, and pharmacists can say “please make sure your children have their measles vaccine if you’re going overseas”.’

Children under 12 months (but over 6 months) of age travelling to an area where measles is circulating can receive one dose of the MMR vaccine to ensure some protection against the virus.

However, the child will still require two doses of the MMR vaccine at 12 and 18 months of age for a sufficient immune response.

6. Parents of neurodivergent children are more concerned about needle phobia than autism risks

In recent research, Prof Danchin and team asked both parents of children with autism and neurotypical children about the MMR vaccine.

Among parents of children with autism, the main barriers were behavioural difficulties and needle phobia, rather than fears the vaccine would exacerbate autism or cause autism in siblings.

To boost vaccination rates in this group, children with severe needle phobia can be referred to specialist immunisation clinics that offer an array of distraction techniques and conscious sedation. These services are available in every state and territory.

‘Nitrous oxide can be given to kids at immunisation drop-in clinics,’ she said. ‘Or children can be admitted to medical units for both oral medication and nitrous oxide for sedation.’

This is particularly pertinent in some children with autism, who need sedation due to severe anxiety or behavioural difficulties.

7. Answers on low vaccine uptake are coming

To understand the drivers of lower vaccination rates, Prof Danchin and team are conducting an Australia-wide project with the NCIRS and the University of Sydney, with results expected mid-year.

The research will endeavour to understand access and acceptance factors by state and region, with the intention to track them over time.

‘It’s important to know what communities have low coverage and where we need to boost vaccination rates,’ said Prof Danchin. ‘But to do that, we need to know why there’s low coverage, and develop solutions tailored to those areas.

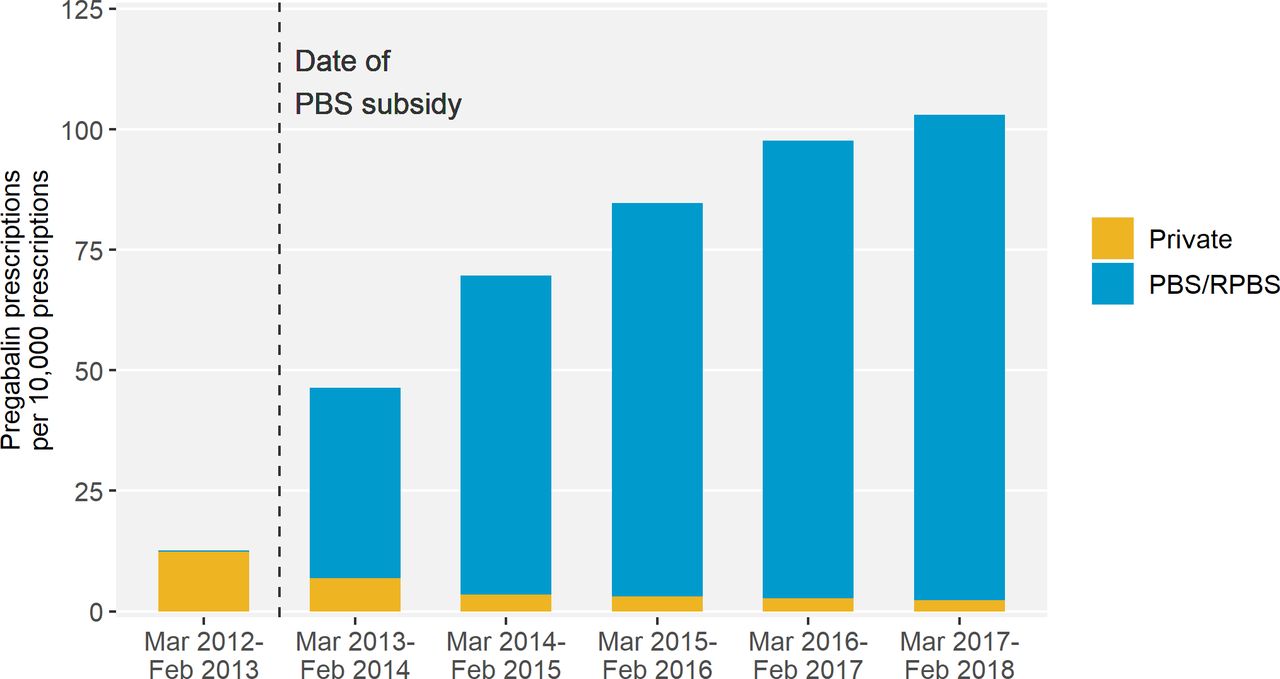

Source – Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012–2018: a cross-sectional study[/caption]

Source – Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012–2018: a cross-sectional study[/caption]

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]

Prof Danchin is a consultant paediatrician at the Royal Children’s Hospital and Clinician Scientist, University of Melbourne.

Prof Danchin is a consultant paediatrician at the Royal Children’s Hospital and Clinician Scientist, University of Melbourne.