Growing in scale, how can pharmacists make sense of the increasing complexities associated with compounding?

Once the domain of tinctures, mixtures and creams, compounding has evolved to include everything from lozenges to skin patches and sterile injectable medicines.

It is a necessary option for patients whose needs cannot be met with existing commercial products, which may be more Australians than usual, given that more than 400 medicines are currently out of stock or unavailable.1

Compounding is growing in both scale and complexity. In 2002, there were about 12 specialist compounding pharmacies in Australia. By 2017, there were more than 500.2

With greater scale and complexity comes increased risk. And this is something regulators are becoming increasingly concerned about.

A prominent example of this is the recent media coverage of compounded semaglutide, which alleged high-volume distribution of a compounded version of injectable semaglutide. Among the allegations were claims of non-sterile production of an injected therapeutic agent, and grossly inadequate cold chain, as well as various fraud allegations.3–7

While this case may be an extreme example, and may involve criminal behaviour, it points to examples of quality and safety concerns where risks are not effectively managed.

The federal government announced last month that from 1 October new regulations will remove glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), many of which claim to be replicas of Ozempic or Mounjaro, from the pharmacy compounding exemption.8

A 22 May media release from federal Health Minister Mark Butler stated: ‘At least 20,000 Australian patients are injecting these compounded replica weight loss products. The majority are using this for weight loss management.’8

According to Victorian Pharmacy Authority (VPA) Chair David McConville MPS, ‘the majority of compounding pharmacies meet the relevant requirements and provide an important service to the community’.

However, risk management is one of the most misunderstood aspects of the Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook (APF) guidance, says PSA Senior Professional Practice Pharmacist Carolyn Allen MPS.

The APF specifies that a systematic risk assessment must be conducted and documented for each compounding request, including repeat prescriptions.

Mr McConville says pharmacists should always approach compounding ‘with risk management front of mind’.

‘Where in doubt, or in the absence of documented and established evidence for safety, efficacy, and stability, pharmacists should make the decision not to compound,’ he says.

‘Much of the non-compliance the VPA sees is a result of pharmacists lacking awareness of their legal and professional obligations, especially in novel or emerging areas.’ For example,

pharmacists’ legal obligations regarding compounding of nicotine for vaping

have recently changed.

What does a systematic risk assessment look like?

As described in the APF, risks can be broadly categorised as patient-related, formulation-related, personnel-related, premises-related, and regulation-related.

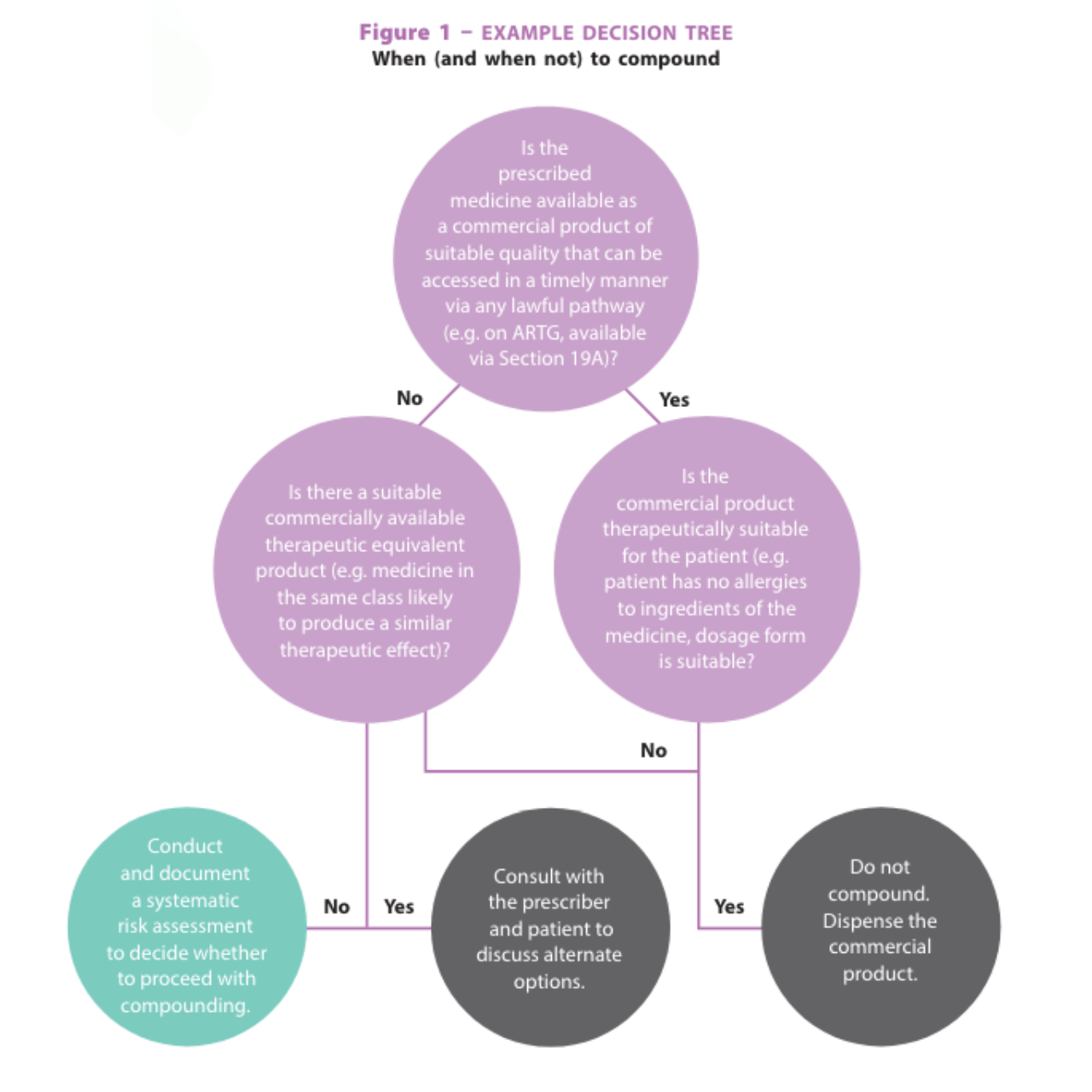

A systematic risk assessment must assess the risks related to each of the factors in these categories relevant to a particular compounding request. A risk assessment tool, such as the APF Decision support and risk assessment tool can help to assess the risks and determine whether compounding should proceed (see Figure 1). For example, the pharmacist must assess whether they have the appropriate containment equipment (e.g. a powder hood) for compounding a hazardous medicine. If they do not have the appropriate equipment, they must not compound the medicine.

Instead, they must refer the patient to a compounding pharmacy equipped for compounding the hazardous medicine.

In another example, if a non-sterile preservative-free aqueous formulation

is requested, the pharmacist must assess whether the formulation can be refrigerated.

If the formulation cannot be stored refrigerated (e.g. refrigeration causes precipitation of the active ingredient), it must be supplied in single-dose containers.

If the pharmacist cannot supply in single dose containers, they must not compound the medicine. Instead, they must refer the patient to a compounding pharmacy that can supply the medicine in single-dose containers.

New guidance to manage risks

New guidance to manage risks

The updated APF (APF26 print and APF digital) has overhauled advice for compounded medicines in a number of areas to help manage risks to patients.

In particular, the updated APF contains more explicit information about quality assurance requirements. This includes detailed guidance about expiry dates with expiry date tables which set out the information in a clear and accessible format (see Table 1, p23).9

‘The recommendations for expiry dates for various types of products have been based on the criteria contained in the US Pharmacopeia (USP), with adaptations for the Australian regulatory environment,’ says Emeritus Professor Lloyd Sansom AO FPS, the long-time

chair of the APF Editorial Board.

APF: your first stop for compounding guidanceThe Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook (APF) should be every pharmacist’s first port of call for aauthoritative guidance on compounding, whether seeking information on a coal tar cream or preparing injectable medicines. The latest edition, both APF26 print and APF digital, contains the most important update on compounding seen for many years. What has changed? New and updated guidance on:

Why make these changes? ‘A number of factors have prompted an expansion of the APF compounding guidelines,’ says Emeritus Professor Lloyd Sansom AO FPS. ‘There has been an increase in the number of pharmacies offering compounding services and compounding sterile medicines, the US Pharmacopeia has issued updated guidelines, the Pharmacy Board is reviewing its compounding guidelines and shortages ‘As for every new edition of the APF, the opportunity is taken to examine the current environment and to ensure pharmacists are aware of their responsibilities in regard to compounding, particularly complex compounding.’ |

Compounding sterile medicines

The updated APF includes a new chapter dedicated to guidance on preparing sterile medicines.

Sterile medicines ‘carry a greater risk of adverse outcomes from contamination,’ Emeritus Prof Sansom says, and the compounding, manipulation or repackaging of sterile medicines is classified as complex compounding.

Mr McConville says this is ‘an area of heightened focus’ for the VPA ‘due to recent concerns about the safety of some compounded sterile medicines’.

‘Pharmacies in Victoria undertaking sterile compounding are subject to additional requirements and scrutiny due to the significant public health and safety

risks associated with compounding sterile medicines,’ he says. ‘Pharmacies undertaking sterile compounding must have cleanrooms and equipment which meet relevant standards, are subject to a mandatory expert risk assessment every 3 years to mitigate any associated risks and should expect more frequent inspections by the VPA.’

For pharmacists involved in simple or complex compounding, Mr McConville says there are a few aspects to consider from a compliance perspective. These include ensuring cleanliness and hygiene; not compounding in anticipation of receiving a prescription; ensuring pharmacists and support staff are adequately trained and supervised; and

undertaking routine risk assessments in accordance with Australian Pharmacy Board guidelines and the APF.

Emeritus Prof Sansom says pharmacists should consult the APF for simple and complex compounding alike. ‘Pharmacists undertaking any compounding are recommended to review whether the processes and documentation they use comply with the professional standards and recommendations in APF,’ he says.

Emeritus Prof Sansom says pharmacists should consult the APF for simple and complex compounding alike. ‘Pharmacists undertaking any compounding are recommended to review whether the processes and documentation they use comply with the professional standards and recommendations in APF,’ he says.

Reference for the modern pharmacist

Compounding has been part of pharmacy practice since the profession first began, and pharmacists have long been celebrated for their ability to create medicines for those in need.

In 1899, a South Australian newspaper praised local ‘chemist and druggist’ Mr H. Glover for his preparation of prescriptions: ‘[He] is much sought after … His stock is fresh and pure, and Mr Glover carefully and accurately compounds physicians’ prescriptions. The suffering public should take the first opportunity of meeting him.’10

Emeritus Prof Sansom says today compounding remains just as relevant.

‘The demand for compounding services will continue, but it needs to be undertaken in a framework of best practice by pharmacists who have the required competencies, equipment and facilities,’ he says.

Luckily for today’s pharmacists, unlike Mr Glover, in the APF they have a comprehensive and up-to-date compounding reference to guide them.

References

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Medicine shortage reports database. 2024. At: apps.tga.gov.au/Prod/msi/search?shortagetype=All

- Weekes L, Razman I. Prescription of compounded ophthalmic medications – a pharmacy perspective. Clin Exp Optom 2021;104(3):406–411.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Search warrant executed on South Yarra pharmacy. 2024. At: www.tga.gov.au/news/media-releases/search-warrant-executed-south-yarra-pharmacy.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Search warrant executed on Sydney residence in relation to substandard compounded semaglutide. 2024. At: www.tga.gov.au/news/media-releases/search-warrant-executed-sydney-residence-relation-substandard-compounded-semaglutide

- Worthington E. Melbourne compounding pharmacy raided as part of probe into alleged copycat Ozempic manufacturing. 2024. At: www.abc.net.au/news/2024-03-01/melbourne-compounding-pharmacy-raid-ozempic-weight-loss-drugs/103528992

- Worthington E, Robinson L, Wiggins N. ABC. Four Corners. The hunt for the Australian ‘coyboy’ pharmacist behind a replica Ozempic and Mounjaro scam. 2024. At: www.abc.net.au/news/2024-04-01/cowboy-pharmacist-behind-a-replica-ozempic-and-mounjaro-scam/103644794

- Worthington E. Patients report alarming side effects after injecting Ozempic and Mounjaro. 2024. At: www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-14/replica-ozempic-and-mounjaro-side-effects/103654198

- Sansom LN, ed. Australian pharmaceutical formulary and handbook. 2024. At: https://apf.psa.org.au

- Border Watch. H Glover chemist and druggist. 1899. At: nla.gov.au/nla.news-article81713454

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

National Medicines Symposium 2024 speakers (L to R): Steve Waller, Professor Jennifer Martin, Professor Libby Roughead, Tegan Taylor[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]

This CPD activity is sponsored by Reckitt. All content is the true, accurate and independent opinion of the speakers and the views expressed are entirely their own.[/caption]