Pharmacies play a vital role in supporting communities during natural disasters, but just how well prepared are pharmacists and staff for a devastating event?

Emmanuel Pasura MPS, the pharmacist-in-charge at remote Mallacoota Pharmacy, worked non-stop for weeks after day turned to night on New Year’s Eve morning and a raging fire roared towards the town, forcing thousands to the beach and boats where they saw in 2020.

‘Just a few weeks before the fire I started ordering increased quantities of medicines like Ventolin (salbutamol) and antibiotics – just in case,’ he said.

With ash, thick smoke and poor air quality adding to asthma risks in the vulnerable, he had run out of puffers within an hour of opening the pharmacy the previous day.

It was the start of a nightmare logistical effort to get supplies of salbutamol, masks and other essential medicines into the tiny town on the eastern-most tip of Victoria. During the annual Christmas holiday season the population swells dramatically to about 5,000 people.

Thousands of evacuated tourists and locals camped on the beach and in boats that night to outrun the flames that razed up to 300 homes and felled bushland that closed the only road out for at least a month.

Raj Gupta, the only pharmacist in the tiny NSW South Coast town of Malua Bay, was forced into emergency accommodation in Batemans Bay, the Shoalhaven area hard-hit by the relentless fires that destroyed swathes in and around nearby towns.

Mr Gupta continued dispensing in the dimness of his power-less pharmacy to keep local residents in necessary medicines while the 3-day supply rule remained in effect in NSW up to 7 January.

‘There’s been no power, there’s been no communication [so] we can’t take payments, but that’s not much of a concern. People will come back and pay. They are very honourable people,’ Mr Gupta told SBS at the time.

His and other heroic efforts by pharmacists in the worst-hit areas of NSW, Victoria and Kangaroo Island off South Australia – where supplies eventually were brought in by helicopter, police barge, navy vessel, cargo ship, ferry and even jet skis – were examples, according to PSA National President Associate Professor Chris Freeman, of ‘pharmacists going above and beyond for their communities’.

His and other heroic efforts by pharmacists in the worst-hit areas of NSW, Victoria and Kangaroo Island off South Australia – where supplies eventually were brought in by helicopter, police barge, navy vessel, cargo ship, ferry and even jet skis – were examples, according to PSA National President Associate Professor Chris Freeman, of ‘pharmacists going above and beyond for their communities’.

But were pharmacists prepared for a disaster that has changed the federal government rhetoric on climate change?

Were disaster plans adequate to meet a permanent shift in fire risk that now threatens the survival of many species of birds and animals, urban catchments, water security and the permanence of infrastructure?

Australia is no stranger to sudden natural disasters. Bushfires, cyclones, floods – 300 millimetres of rain fell in just hours around the Gold Coast during a 1-in-100-year thunderstorm while fires still burned elsewhere last month – a community somewhere in Australia has been affected.

Yet, according to Queensland University of Technology (QUT) researcher Dr Elizabeth McCourt, pharmacists are 1.7 times more likely to have experienced a natural disaster than they were to have received previous education or training for a disaster.

‘That, to me, is quite shocking,’ said Dr McCourt, a hospital pharmacist whose research focuses on the preparedness of pharmacists for disasters and emergencies.

‘It shows just how scarce training, information and resources are for pharmacists in this area.’

Responding to disasters – FIP disaster guidelinesThe Responding to disasters: Guidelines for pharmacy document produced in 2016 by the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) break down emergency management into different phases, designated generally PPRR:

The guidelines pose questions that should be considered at the national, regional and individual pharmacy levels during each of the above four phases and are not intended to answer all the questions. Instead they aim to raise awareness of what pre-planning pharmacists should consider. For more information visit: |

An essential service

Consider this: if the above statistic was cited for SES members, firefighters, energy and communications technicians, or paramedics it would likely prompt an inquiry, just as the mega-fires, the first of which in NSW was ignited by a lightning strike in October, have prompted two state inquiries and a mooted Royal Commission.

After all, those roles are all categorised as ‘essential services’ during natural disasters. But so, too, are pharmacists.

‘A lot of people would be familiar with language such as “unless you’re an essential service, stay off the roads”. Well, community pharmacies are considered to be essential services,’ explained Paul Willis, the General Manager of Cate’s Chemists group in Townsville.

‘That message is often misunderstood. It doesn’t say emergency services – it’s essential services. And it’s important we train our pharmacy staff to respond to that message appropriately.’

Lessons learned

Mr Willis and his pharmacist wife Cate Whalan know about preparing for, and responding to, natural disasters.

The duo and their staff not only helped the Townsville community through severe tropical cyclone Yasi in 2011, but in February 2019 supplied medicines throughout disastrous flooding that brought the region to a standstill.

‘Community pharmacy is an essential part of the public health system during a disaster or an emergency. They’re very well positioned and accessible to the community,’ Mr Willis said.

‘There’s a lot of fear and apprehension during situations like this so pharmacies provide an element of normalcy, too – if an important part of the health system is operating normally, that provides psychological reassurance to patients.’

Another QUT researcher, Dr Kaitlyn Watson, added: ‘Research shows patients leave their homes without their medicines, without their ID and without money, typically.’

A registered pharmacist whose research focuses on the legislation and roles aspects of pharmacists in disasters, Ms Watson said pharmacists she’s interviewed ‘decided they had a duty of care to their community to stay open and gave out emergency supplies to patients at the cost to their business, not the patient’.

Added Mr Willis: ‘You can make arrangements for people to come back and pay next week but it’s chaotic and it ends up being more work to chase up.’

Preparation and planning

‘In disaster management there’s this thing called “all hazards preparedness” –

if you’re preparing for one type of disaster, it should help you prepare for another,’ Dr McCourt said.

‘Many of the core concepts will be the same, like: Who do we talk to? Who do we call? What’s the chain of command? How do we get more stock in? Where’s our relocation point?’ she explained.

This will also help pharmacies take out appropriate insurance cover in advance.

‘We weren’t covered for the flooding,’ said Jessica Burrey, owner of the Emerald Plaza Pharmacy in Emerald, a regional town in central Queensland.

In 2010, a flood washed mud from the nearby Nogoa River through more than 1,000 homes and damaged 95% of the town’s businesses. ‘At the time I was an employee pharmacist, but from a business perspective it was a big lesson.’

Another early preparation step involves connecting with your primary health network (PHN) and local disaster management group, added Mr Willis.

‘In our area they offer great training activities and do rehearsals, such as little war games and scenarios. They’ve also got access to a lot of training resources and can force us all to think through the consequences of some of these events,’ he said.

Such a group can help identify occupational health and safety issues, such as road reconnaissance and appropriate high-visibility disaster attire for staff.

‘A lot of traditional pharmacy uniforms – the nylons, the polyesters, skirts and court shoes – are completely inappropriate in a disaster situation,’ Mr Willis said.

By developing contingency plans with Primary Health Networks in advance, uncertainty and inefficiencies in the middle of the disaster can be prevented.

‘Linking in with local GPs and hospital pharmacy departments is really important,’ Dr McCourt said.

‘It’s important to ask them, “What’s your plan? What if this happens? Who can we send resources to? How are we even going to communicate with you in a disaster aftermath?” Those things need to be figured out in advance rather than on the fly.’

Emergency supply provisions

It’s particularly critical to establish how to communicate with prescribers to obtain a verbal prescription. Outside recent temporary provisions [until the end of March] that allow full supplies of medicines, usually up to a month’s worth, without a prescription in NSW,1 Victoria,2 the Australian Capital Territory3 and Kangaroo Island,4 current legislation only permits pharmacists who are elsewhere in Australia to supply patients with 3-day emergency provisions.5

All temporary emergency provision medicines are also available at PBS prices from 13 January until 31 March, following intervention by the federal Health Minister Greg Hunt.6

‘Our research is showing when a disaster occurs three days is not actually long enough to handle the impact on the community services,’ Dr Watson said.

In scenes repeated in many other towns, 130 kilometres north of Eden, NSW, the team at Narooma Pharmacy, part of the Capital Chemist Group, set up a makeshift pharmacy at the evacuation centre at the Narooma Leisure Centre.

Managing Partner Danielle Campbell MPS and her colleagues loaded a ute with pharmacy supplies including nappies, masks, asthma relievers and other medicines. At the evacuation centre, the team set up a table and was joined by a local GP who wrote prescriptions while Ms Campbell dispensed them, writing labels by hand.

The mental and emotional toll

Be warned of likely witness trauma unfolding during a natural disaster. In many cases, patients will have lost homes, pets and sometimes even family members.

Two fathers and sons died in historic Cobargo, NSW, and on Kangaroo Island in the recent bushfires. At Culburra Beach, east of Nowra, Culburra Pharmacy owner David Heffernan MPS had the devastating task of balancing professional obligations with personal tragedy. A friend, who tried to save another friend’s apple orchard from the fires, died after a cardiac arrest.

Canberra pharmacist Kayla Lee MPS, who developed the innovative program Pharmafriend, said mental health first aid is a must for pharmacists.

‘While it’s not a requirement for pharmacist registration at this point in time, it’s a two-day course that gives you skills to be able to deal with crisis management,’ she said.

‘Personally, I’ve applied the skills learned in mental health first aid much more frequently than my regular first aid training.’

Don’t forget to take stock of your own mental health, Dr McCourt said, as you won’t know how you’ll react until the situation unfolds.

‘And be honest with yourself. We’ve all experienced a time when we are so tired, so stressed, so run down and we just think “I’m really not safe to practice right now”,’ she said.

‘You’re going to be working without air-conditioning, you might not have running water, you’re going to have people coming in who you’re very worried about, they’re going to be telling you awful stories of things that have happened to them; it’s really hard to continue practicing safely in that environment.’

Pharmacists affected by the fires can contact Pharmacist Support Services on 1300 244 910.

Disaster roles for pharmacists

Before the events of September 11, 2001 and the twin towers of the World Trade Centre collapsed, accepted roles for pharmacists generally focused on contributions to logistics and supply chain management.

But pharmacists are capable of so much more, as is evident in their actions during the recent Australian bushfires.

As devastating as these recent bushfires have been for communities and Australia, it is great to see pharmacists being recognised for their contributions to the response and recovery efforts, said Dr Watson, from Edmonton, Canada, where she is now based.

‘My heart goes out to all those pharmacists and colleagues working in these challenging circumstances and to those pharmacists and their families that have suffered personal losses as well.’

She urged pharmacists working in bushfire-affected regions to look after themselves as well as continuing the great work they are doing for the community by providing essential pharmacy services.

It has been heartwarming to see pharmacists be supported in their response efforts with the temporary changes made to emergency supply rules and PBS medicines, Dr Watson said.

‘I hope these changes become integrated into legislation across the states and territories, ready for whatever and wherever the next disaster might be.’

Pharmacists are the most widely distributed healthcare practitioner in the community, available on the frontline in disasters to provide essential ongoing healthcare.

With the new temporary emergency supply arrangements, pharmacists are able to assess and prescribe ongoing medicine needs for patients, providing up to a month’s supply – freeing up emergency departments and other healthcare services to treat higher-acuity injuries from the bushfires.

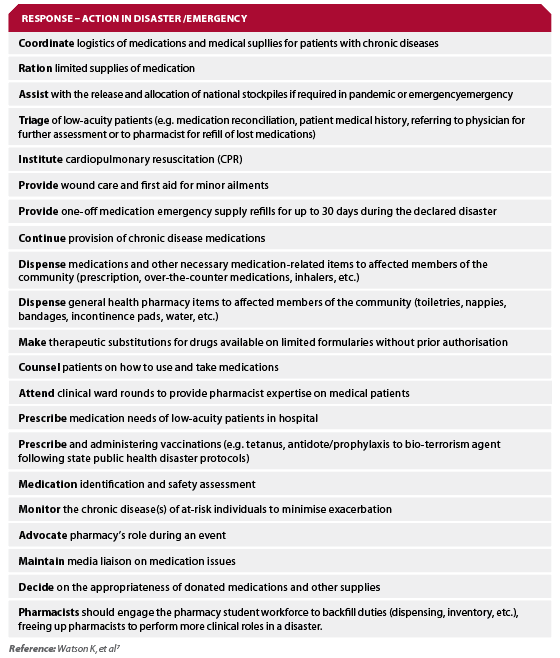

However, there are 43 roles in total that pharmacists could and should be undertaking throughout all phases of a disaster, as highlighted in Dr Watson and colleagues’s latest prescient research, published online on Boxing Day 2019.

They identified the roles that a panel of 15 experts from international and Australian non-governmental organisations, government, pharmacy, military, public health, and disaster management agencies have deemed pharmacists are capable of undertaking during any disaster.7

Dr Watson presented to the World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine (WADEM) Congress in Brisbane in May last year that the 43 roles identified by the expert panel were broken into the four phases of disaster management – prevention, preparedness, response and recovery (PPRR).7 The majority of these roles are in the response phase. (See Box 1.)

Until now, pharmacists have operated pharmacy disaster management responses with limited formal guidelines to follow, and separately to the coordinated health response.

To undertake these roles effectively, pharmacists should work within the coordinated disaster management and public welfare team structure, Dr Watson stated.

‘It is imperative that primary healthcare (including pharmacists and GPs) are integrated into disaster health teams and [are]part of the coordinated response before a disaster strikes.’

‘It is important that we offer trainings and resources to all pharmacists to be prepared for disasters – including offering trainings for more disaster-specific specialised pharmacist roles and providing avenues for pharmacists and their colleagues for debriefing/ongoing support during the recovery phase which can go on for weeks to years,’ Dr Watson says.

‘My colleagues and I are happy to consult and assist in the development of trainings and continuing professional development (CPD) material.’

‘Together, pharmacy professional bodies and policymakers can provide better integration of pharmacists’ roles in disaster management teams, whether assisting in the community or on deployment,’ Dr Watson says.

BOX 1– Consensus on 21 roles pharmacists could undertake in the response phase of a disaster

Resources for pharmacistsThese resources, training modules and support services can help pharmacists deal with greater-than-usual mental health presentations in the aftermath of a disaster.

|

References

- NSW Government Health Department. Advice for pharmacists supplying medicines to patients in areas affected by NSW Bushfires – 13 January 2020. At: www.health.nsw.gov.au/environment/air/Pages/community-pharmacists.aspx

- Victoria State Government. Advice for pharmacists supplying medicines to patients in areas affected by Victorian Bushfires. 2020. At: www2.health.vic.gov.au/public-health/drugs-and-poisons/supplying-patients-affected-by-bushfires

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. ACT joins NSW and Victoria in improving access to medicines for people affected by bushfires. 2020. At: www.psa.org.au/act-joins-nsw/

- Steven Marshall, Premier of South Australia. Prescription pressure lifted in emergencies. 2020. At: www.premier.sa.gov.au/news/media-releases/news/prescription-pressure-lifted-in-emergencies

- PBS News. Advice for approved pharmacists supplying PBS medicines. 2019. At: www.pbs.gov.au/info/news/2019/11/advice-for-approved-pharmacists-supplying-pbs-medicines

- Greg Hunt, Minister for Health. Ensuring continued access to affordable PBS medicines for those impacted by the bushfires. 2020. At: www.greghunt.com.au/ensuring-continued-access-to-affordable-pbs-medicines-for-those-impacted-by-the-bushfires/

- Watson KE, Singleton JA, Tippett V, et al. Defining pharmacists’ roles in disasters: a delphi study. PLoS ONE 2019;14(12):e0227132.

- Watson KE, Singleton JA, Tippett V et al. The verdict is in: pharmacists do have a role in disasters and it is not just logistics. Prehosp Disaster Med 2019;34(Suppl 1):s63.

- Ochi S, Hodgson S, Landeg O et al. Disaster-driven evacuation and medication loss: a systematic literature review. PLOS Current Disasters 2014;6.

- Jenkins JL, Hsu EB, Sauer LM, Hsieh YH, Kirsch TD. Prevalence of Unmet Health Care needs and description of health care-seeking behavior among displaced people after the 2007 California wildfires. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2009 Jun;3(2 Suppl):S24–8.

- Tomio J, Sato H, Mizumura H. Interruption of medication among outpatients with chronic conditions after a flood. Prehosp Disaster Med 2010;25:42–50.

- Krousel-Wood MA, Islam T, Muntner P et al. Medication adherence in older clinic patients with hypertension after Hurricane Katrina: Implications for clinical practice and disaster management. Am J Med Sci 2008;336(2):99–104.

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more