Coronavirus (COVID-19) information for pharmacistsFor PSA’s latest information, updates and advice on the novel coronavirus outbreak, click here.

Pharmacists, the most accessible healthcare professionals, are often the first point of contact for unwell individuals. They should be involved in drafting pandemic preparedness plans.

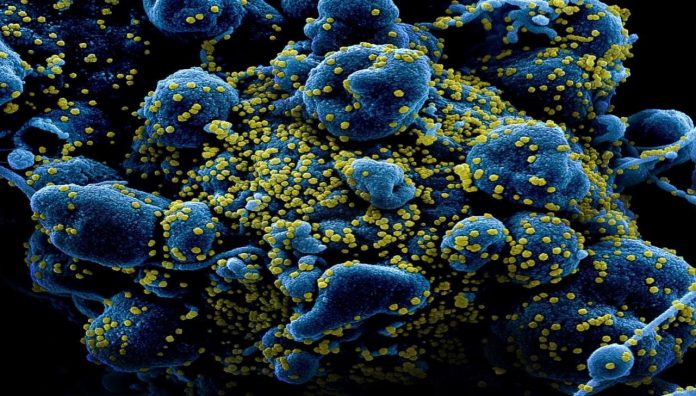

Coronaviruses are usually associated with the common cold, a self-limiting viral infection; however, they are increasingly the cause of more severe, disabling and deadly infections. Notably, they were responsible for the 2003 outbreak of SARS-CoV (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus), the 2012 MERS-CoV (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus) and now COVID-19, caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2).

The COVID-19 virus was first reported in Wuhan, China, on 31 December, 2019. By 24 March there were nearly 400,000 cases and more than 16,000 deaths. More than 170 countries had reported confirmed cases.1,2 Less than one-third had yet recovered in those 3 months.

In Australia, more than 5,844 cases had now been confirmed, with 42 deaths.

On 18 February 2020, the Commonwealth released the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19),3 weeks before the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on 11 March.

The Federal COVID-19 Plan provided national advice and guidance, facilitating a consistent approach across all states and territories. Prior to this plan, concerns were raised about the inconsistent guidance given across Australia on how to best manage the virus. While pharmacists were not involved in the drafting of the plan, it did identify that pharmacists were important stakeholders, stating that in addition to the Australian Government Department of Health and state and territory health departments, ‘Nongovernment parties, such as GPs, nurses and pharmacists will also be involved in responding to a pandemic’.

How will pharmacists, on the front line of primary care,4 support a coordinated, efficient and rapid response to reduce coronavirus-related hospitalisation and mortality? We know from research that pharmacists’ perceived preparedness for a public health emergency of international concern is generally not as high when compared to doctors and nurses.5 There have also been concerns from the pharmacy profession about the lack of inclusion of pharmacists in pandemic preparedness coordinated by Government. But despite perceived preparedness, pharmacists play a key role in epidemic and pandemic responses.6

In early February, the International Pharmaceutical Federation released Coronavirus 2019-nCoV outbreak: information and interim guidelines for pharmacists and the pharmacy workforce,7 providing information and guidance on the roles and responsibilities of pharmacists working across the sectors – community, hospital and public health – to reduce the spread of novel coronavirus. Many important aspects were covered, including preventative measures, pharmacy as an information source, appropriate referral and isolation. There is a case for the role of the pharmacist to be expanded to improve the pandemic public health response.

Screening

People with acute respiratory symptoms routinely present to pharmacies seeking treatments, both prescribed (e.g. antibiotics and antiviral) and over the counter (e.g. nasal decongestants, antipyretics and pain relievers). Pharmacists can thus identify and screen individuals for potential COVID-19. Where an individual with respiratory symptoms has travelled to China, Iran, South Korea or Italy (including transit) or had close or casual contact with a potentially infected individual, the pharmacist should suspect COVID-19.8 The pharmacist should provide the individual with a single-use face mask (or surgical mask, face shield) and advise them to self-isolate and seek prompt medical assessment, by calling ahead to their GP. GPs will call the local hospital emergency department where appropriate. Walk-in centres have been set up to assess and test individuals with respiratory symptoms. In Australia, the current test is swabs from the back of the nose and throat or fluid from the lungs. As cases increase, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is a priority. On 8 March, the Australian Government announced community pharmacies were eligible to access the Government surgical mask supply for the use of staff with no available commercial supply. Masks are available through Primary Health Networks. Government-supplied masks are not to be sold as retail stock.9

Pharmacy staff need to be extra vigilant during this pandemic. Those with significant contact with individuals presenting with fever or respiratory symptoms can employ workplace social distancing (1.5–2 metres) and use masks. Recent data suggests that approximately 30% of COVID-19 cases are asymptomatic.

Face masks

The outbreak of coronavirus has increased demand for face masks, by up to 100- fold, severely depleting the global supply.10 A single-use face mask is fitted across the nose providing a physical, protective barrier around the wearer’s nose and mouth to interrupt the spread of respiratory droplets from the wearer, as well as from infected people and, in theory, should reduce community transmission of infectious microorganisms.11

Mask use effectiveness is controversial and its role is limited. Face masks are associated with low adherence and may provide a false sense of security. Individuals not used to wearing a mask will likely touch their faces more frequently and increase chances of self-inoculation.

Disposable respirators (e.g. P2, N95) are designed to protect wearers from infectious aerosols. Respirators can filter out approximately 94% of particles less than 5 microns in size. A meta-analysis of six case-control studies, identified that respirator use during the 2003 SARS epidemic in China, Singapore and Vietnam reduced the risk of infection.12

Prices of respirators have skyrocketed. The wholesale price of Livingstone Pty Ltd P2 masks recently increased from $2.50 to $38.50 per unit. Current advice from the WHO and the Australian Government states that healthy individuals need not wear a face mask unless directly caring for a person with suspected COVID-19.13

The Government has released masks and respirators from the national stockpile; however, concerns grow of insufficient numbers for health professionals. Individuals who have respiratory symptoms should wear a face mask to reduce spread. Further information on when and how to use face masks can be found at www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/when-and-how-to-use-masks

In the current pandemic, there are concerning reports of people purchasing and stockpiling face masks in bulk. The pharmacy profession’s response to pandemics needs to include mechanisms to ensure evidence-based distribution without placing individuals in need being unable to purchase face masks due to stockpiling. The PSA has called for a national coordination of face mask distribution to include community pharmacies.

Handwashing

A small study (N =26) published in 2015 showed, on average, that individuals touch their face 23 times per hour.14 In general, frequent handwashing remains the greatest protection against infections and reducing transmission. Evidence shows that COVID-19 spreads between people in close contact (within 2 metres) via respiratory droplets and aerosols, produced when an infected person sneezes or coughs. It is also spread via fomites (any surface the virus has landed on) that is then touched and passed from the hands to the nose, mouth or eyes. The virus can survive more than 72 hours after contact with a surface.15

Handwashing remains the cornerstone of infection control for this coronavirus.16 Studies show that both routine hand hygiene with either soap or running water and alcohol-based hand rubs (containing between 60% and 80% v/v ethanol or equivalent) is effective in reducing virus transmission. Pharmacists should counsel individuals on the importance of regular hand hygiene.

Promote uptake of flu vaccination

Health authorities are predicting both the influenza virus and COVID-19 will co-circulate during the Australian winter months. Both are respiratory infections with overlapping symptoms. The Commonwealth considers influenza vaccination uptake and the timing of both non National Immunisation Program (NIP) and NIP vaccines to be a measure to support and contain recovery associated with COVID-19. To improve influenza vaccination uptake, NSW and Queensland regulations were recently modified so pharmacists could administer the vaccine to children aged ≥10 years, bringing them into line with Western Australia, Victoria and Tasmania.17 Pharmacists should recommend annual influenza vaccination for everyone aged ≥6 months.

The influenza vaccine arrived in pharmacies in early March 2020. NIP influenza vaccines will be available to the public 4–6 weeks later. As vaccination timing is important for the containment and recovery of COVID-19, the following advice can be given by pharmacists:

- People should have the influenza vaccine before the onset of each influenza season. In most areas of Australia peak influenza season is from June – September.

- The greatest protection against influenza occurs within the first 3–4 months following vaccination; however, protection is generally expected to last the whole flu season.

- People caring for young, older or vulnerable people (e.g. pharmacists, aged care workers, childcare workers), should be vaccinated immediately.

- Those eligible for the NIP vaccine should wait until April, but can choose.

- People aged ≥65, should almost definitely wait until April. Fluad Quad® contains adjuvants, boosting immunogenicity in people ≥65 years.

- If unvaccinated while influenza viruses circulate, there is benefit in the vaccine, irrespective of time left in the season.

- Revaccination later in the same year is not routinely recommended; however, for some individuals it may be appropriate (e.g. travel or pregnancy).9

All flu vaccines available in 2020 are quadrivalent influenza vaccines (QIVs) and are 0.5 mL doses for all ages (see Table 1).

TABLE 1 – Registered vaccines for the 2020 influenza season8

| TRADE NAME | MANUFACTURER | REGISTERED AGE GROUP |

| QUADRIVALENT VACCINES (ALL INACTIVATED) | ||

| FluQuadri | Sanofi | ≥6 months |

| Vaxigrip Tetra | Sanofi | ≥6 months |

| Fluarix Tetra | GSK | ≥6 months |

| Afluria Quad | Seqirus | ≥5 years |

| Influvac Tetra | Mylan | ≥3 years |

| Fluad Quad | Seqirus | ≥65 years |

Alert but not alarmed

This is the sixth global pandemic in just over 100 years. For most, it is the first to impact daily life. Countries, including Australia, have shut borders to non-citizens and non-residents. Air travel worldwide has all but halted and domestic travel deemed not necessary has also stopped. Many airlines have grounded most of their fleets. This has significantly impacted Australian universities, most of which have or are moving to online course offerings to help enable physical distancing. Each day brings cancellations or postponements of major international events, conferences and cultural festivals, including the Tokyo Olympic Games. In Australia, working from home is becoming the norm as states have shut borders, schools close and RACFs head towards lockdown.

Australians, and people globally, have been in panic mode for weeks. While the mortality rate (1–3%) is comparably low relative to previous pandemics, COVID-19 is one of the most highly infectious. Panic is impacting community pharmacy sales with panic buying of alcohol wipes, sanitisers, toilet paper and face masks nationwide. Stockpiling of medicines has begun, with an increase in patient requests for multiple repeats of medicines, and regulation 49 prescriptions. One reason is fear that Australia will go into lockdown to reduce the spread of the virus, and people will not be able to shop for essentials.

Pharmacists have a role to play in educating the public about COVID-19 in an evidence-based manner. They should reiterate that people should be alert but not alarmed, and reassure individuals that everything is being done to ensure medicines are available.

Resources

The Australian Government has published a range of information resources available both for health professionals and the public on COVID-19 (see Table 2). Information, advice and resources are constantly updated reflecting the latest policy and evidence-based recommendations together with a Coronavirus Health Information Line on 1800 020 080. Pharmacists must be up to date with the latest information and advice, and can call this number seeking more specific information on COVID-19.

TABLE 2 – COVID-19 information resources

| Federal Department of Health Coronavirus (COVID-19) health alert | www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert |

| Federal Department of Health Coronavirus (COVID-19) resources | www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-resources |

| Coronavirus (COVID-19) resources for health professionals | www.health.gov.au/resources/collections/coronavirus-covid-19-resources-for-health-professionals-including-pathology-providers-and-healthcare-managers |

| Coronavirus (COVID-19) information on surgical masks | www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-information-on-the-use-of-surgical-masks |

| WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak | www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 |

| WHO Guidelines on hand hygiene in health care | www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144013/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK144013.pdf |

| Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) information for pharmacists | www.psa.org.au/coronavirus/ |

Promoting vaccination uptake and mass immunisation

Medical research laboratories around the world are working to develop a vaccine against the novel coronavirus. It is anticipated one will be ready for clinical testing by June 2020. Appropriately trained and approved pharmacists across Australia can administer certain vaccines. Many community pharmacies across the country have dedicated treatment rooms, set up for the safe administration of vaccines. Pharmacists can play a role in mitigating the spread of the infectious disease by increasing vaccination uptake. They can also be used in mobile vaccination stations. However, legislation prevents pharmacists playing an immediate role once the vaccine is available. Jurisdictional regulation across all states and territories would need modification for pharmacists to administer a COVID-19 vaccine.

In 2018, as part of a state-wide public health response against meningococcal disease, Tasmanian pharmacists administered meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) vaccines to individuals aged 10–20 years. A total of 66,398 children and young adults were vaccinated with MenACWY during the 11-week response. Pharmacist vaccinators played a key role in increasing vaccination uptake within the narrow time frame. The integration of pharmacists into the public health response highlights their willingness and importance as part of a broader team in a pandemic to improve health outcomes.

Modifying regulations to allow pharmacists to vaccinate (without prescription) in epidemics and pandemics enables proactive rather than reactive preparation when responding to an emerging crisis. A United States study published after the H1N1 pandemic identified that community pharmacies were convenient locations to receive pandemic influenza vaccinations.18

In the event of a pandemic, healthcare resources will be quickly strained. To improve public health outcomes, a coordinated and resourced inter-professional response is required.19 GPs will screen and refer individuals, and patients will access acute care, tying up hospital emergency departments and beds. The role of the community pharmacist in these circumstances should go beyond dispensing medicines, education provision, screening and referral.

As community pharmacies are often an unwell individual’s first point of healthcare system contact, pharmacists and staff are at risk of exposure. Consistent with international recommendations and guidance on pandemic influenzas, pharmacists and their staff should be among the first to be vaccinated against COVID-19.20 Pharmacy services are necessary during a public health emergency and to offer such services at capacity, the pharmacy workforce itself must be protected. If unwell, pharmacy staff should not work.

Pharmacist and pharmacy student preparedness

To effectively deal with any pandemic, pharmacists must be knowledgeable about disease prevention, transmission, symptoms and treatment. Australian pharmacy school curricula are evolving to prepare students for natural and infectious disasters.21 A targeted approach is needed for pharmacy students to develop required graduate attributes to enable competent care provision in challenging environments.

Conclusion

Pharmacists are the most accessible health professional and important stakeholders of the Australian health sector. On 19 March the Minister for Health Greg Hunt thanked pharmacists for around-the-clock work but required them to enforce a 1-month supply limit on certain prescription products and apply it to sales of other OTC medicines to a maximum of one unit per purchase. It followed the 11 March $2.4 billion federal Government health package that included payment for medicine home delivery services. Pharmacists served their communities above and beyond expectation during the 2020 bushfire crisis. They are called upon to do the same during this pandemic.

References

- Johns Hopkins University. Coronavirus COVID-19 global cases. 2020. At: arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

- COVID-19 coronovirus outbreak. 2020. At: www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries

- Australian Government Department of Health. Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19), 2020. At: www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian-health-sector-emergency-response-plan-for-novel-coronavirus-covid-19

- Tsuyuki RT, Beahm NP, Okada H, et al. Pharmacists as accessible primary health care providers: review of the evidence. In: SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA; 2018. At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29317929

- Rajiah K, Maharajan MK, Yin PY, et al. Zika outbreak emergency preparedness and response of Malaysian private healthcare professionals: are they ready? Microorganisms 2019;7(3):87. At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30893885

- McCourt E. Use of pharmacists in pandemic influenza planning in Australia. 2018. In World Hospital Congress, 10–12 October 2018, Brisbane, Qld. (Unpublished). At: eprints.qut.edu.au/122436/

- International Pharmaceutical Federation. Coronavirus 2019-nCoV outbreak: information and interim guidelines for pharmacists and the pharmacy workforce. 2020. At: fip.org/file/4423

- Victoria State Government. 2019-Coronavirus-disease (COVID-19). Victoria. 2020. www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/news-and-events/healthalerts/2019-Coronavirus-disease–COVID-19

- Australian Government Department of Health. Distribution of PPE through PHNs: Tranche 1, Surgical masks and P2/N95 respirators for general practice and community pharmacy. 2020. At: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/03/distribution-of-ppe-through-phns-tranche-1-surgical-masks-and-p2-n95-respirators-for-general-practice-and-community-pharmacy.pdf

- Demand for masks soars 100-fold, disrupting coronavirus fight. Reuters health information. 2020. At: de.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-who-masks/demand-for-masks-soars-100-fold-disrupting-coronavirus-fight-who-idUSKBN20121J

- MacIntyre CR, Cauchemez S, Dwyer DE, et al. Face mask use and control of respiratory virus transmission in households. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15(2):233– At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19193267

- Jefferson T, Foxlee R, Del Mar C, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses: systematic review. BMJ 2008;336(7635):77– 80. At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18042961

- World Health Organization 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: when and how to use masks. At: who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/when-and-how-to-use-masks

- Kwok YL, Gralton J, McLaws ML. Face touching: a frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control 2015;43(2):112– At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25637115

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. At: cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/prevention-treatment.html

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Eng J Med 2020. Epub 2020 Mar. At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32182409

- Queensland Government. Health (Drugs and Poisons) Regulation 1996; Drug therapy protocol – pharmacist vaccination program. In: Health Q, ed. Brisbane: Queensland Government; 2020. At: www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/443983/dtp-pharmacist-vaccination.pdf

- Miller S, Patel N, Vadala T, et al. Defining the pharmacist role in the pandemic outbreak of novel H1N1 influenza. J Am Pharm Assoc 2012;52(6):763– At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23229962

- Rubin SE, Schulman RM, Roszak AR, et al. Leveraging partnerships among community pharmacists, pharmacies, and health departments to improve pandemic influenza response. Biosecur bioterrorism 2014;12(2):76– At: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24697207

- Traynor K. Pharmacists matter in pandemic response. In: Oxford University Press; 2008. At: academic.oup.com/ajhp/article/65/19/1792/5128014

- Madden M, Morrissey H, Ball P. Pharmacy in challenging environments. Australian Journal of Pharmacy 2015;96(1146):60. At: researchoutput.csu.edu.au/en/publications/pharmacy-in-challenging-environments

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more