td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28888

[post_author] => 10042

[post_date] => 2025-04-11 12:00:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-11 02:00:11

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_28205" align="alignright" width="182"] This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

Mr and Mrs Soe come into your pharmacy pushing young Edwin in his pram. Edwin is due for his 6-month vaccinations and has an appointment at his GP coming up this week. The Soe family want to get ‘the best pain and fever medicine they can, because after Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations he was quite upset and had a little bit of a fever afterwards (38.1 ºC)’.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Active immunisation uses vaccines to stimulate the immune system.1 In turn, after the administration of vaccines that contain one or more immunogens, the immune system can react to a toxin or pathogen more effectively, helping prevent or reduce the severity of disease.1 Vaccines may induce antibody production by B lymphocytes, that can bind specifically to a toxin or pathogen.1 They may also boost numbers of killer cells such as CD8+ T cells to kill infected cells, or they may increase CD4+ T cells to help more efficiently ‘clear out’ infected cells.1

Regardless of each vaccine’s mechanism of action, immunity after active immunisation generally lasts for months to many years.2 How long the immune response lasts depends on the nature of the vaccine, the type of immune response (antibody or T-cell) and host factors.1 Because of this, inducing the desired immune response may require a series of vaccine doses.2

The Australian Immunisation Handbook provides clinical guidelines about using vaccines safely and effectively. It outlines the vaccines recommended for children and adults following an evidence-based approach.2 The National Immunisation Program schedule provides a guide to the recommended vaccines and their schedule (See Table 1).2

Edwin’s parents explain that he has kept up to date with all his vaccines so far and has no other health concerns. His 6-month vaccinations are being given in 3 days’ time. Looking at the vaccination schedule, you note that the upcoming vaccination will include diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP); hepatitis B; polio and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). All these vaccinations are now available in one combined product.3 You also note that for Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations, he likely received two injections as opposed to the one, with pneumococcal also required at that time.2

Reactions to vaccinations are common,2 and may include redness, swelling and soreness at the injection site, and sometimes a low-grade fever (38–38.5 °C).4 These reactions are usually mild and self-limiting.2

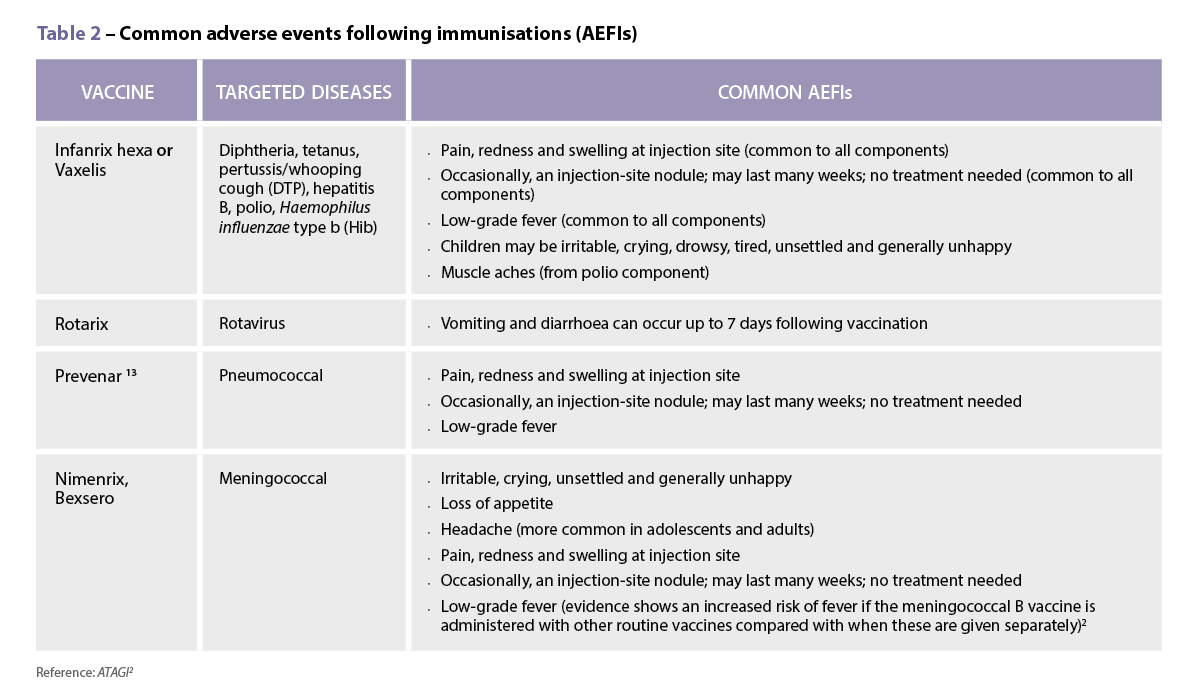

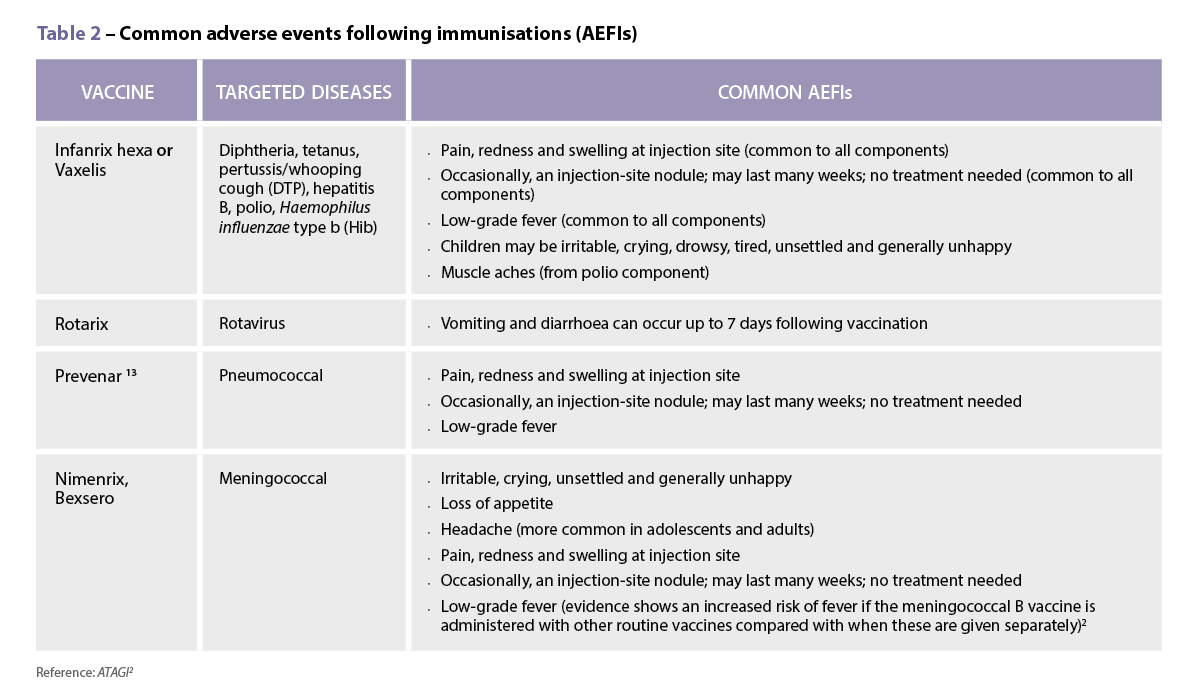

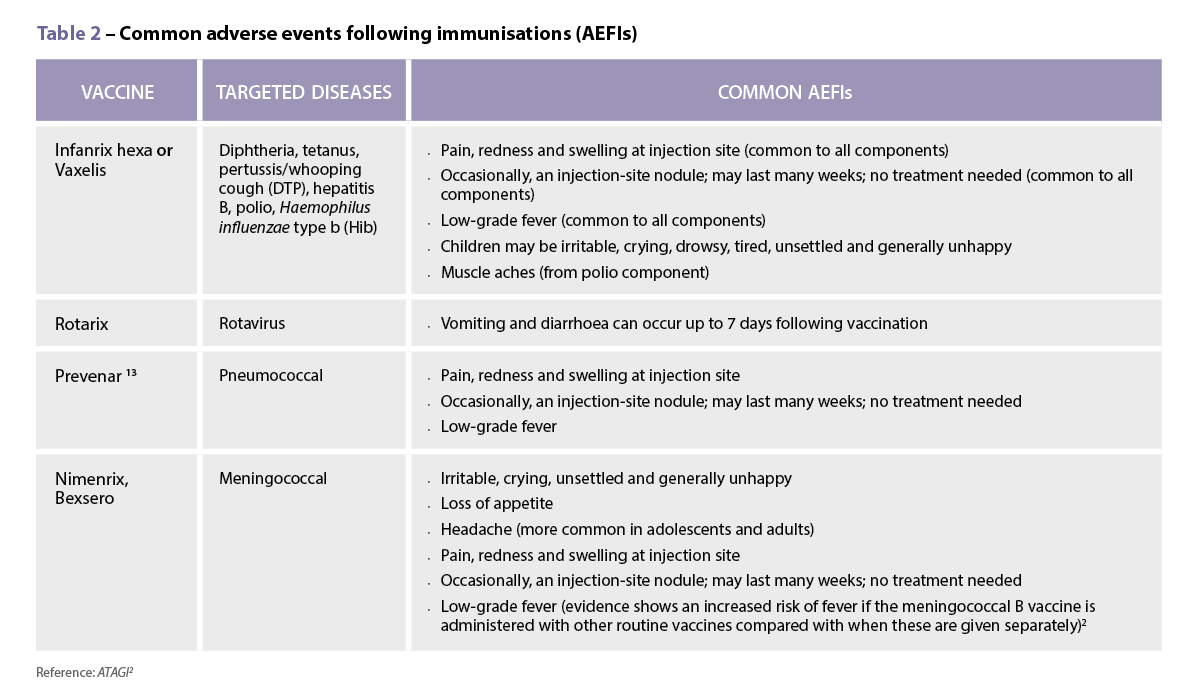

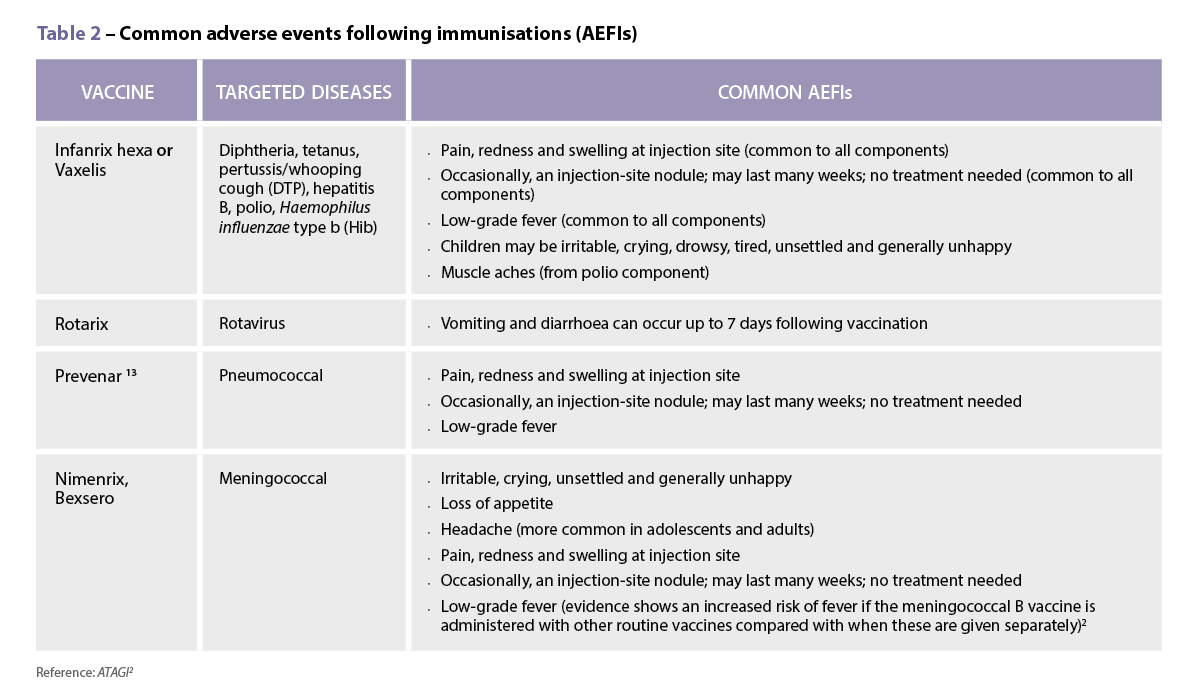

It is likely that Edwin’s low-grade fever and discomfort described by his parents after his 4-month injections were in line with the known common adverse effects associated with childhood vaccinations (see Table 2 ).2

According to the Australian Immunisation Handbook, it is not generally recommended to give a child prophylactic doses of paracetamol or ibuprofen prior to, or at the time of most vaccinations.2 In fact, there is some evidence that interfering with the body’s natural immune response may lower the effectiveness of vaccines.5 In a randomised controlled trial published in the Lancet, researchers demonstrated that antibody response was significantly reduced in the group of healthy infants that received prophylactic paracetamol at the time of both the primary and booster vaccinations for DPT, Haemophilus influenzae and pneumococcal.5

The study concluded that ‘although febrile reactions significantly decreased, prophylactic administration of antipyretic drugs at the time of vaccination should not be routinely recommended, since antibody responses to several vaccine antigens were reduced’.5

In contrast to this advice, however, the immunisation guidelines now recommend a dose of paracetamol 30 minutes prior to the administration of a meningococcal B vaccine.2 The vaccination schedule for healthy infants at low risk of disease recommends MenACWY vaccination at 12 months of age.2 For infants at higher risk of disease, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, they are recommended to also have the meningococcal B vaccine at 2, 4, 6 (with specified risk conditions) and 12 months also. These vaccines have been shown to be associated with the AEFIs listed in Table 2.2

Due to these adverse effects, the Australian Immunisation Handbook suggests that an appropriate 15 mg/kg/dose of paracetamol should be administered 30 minutes prior to – or as soon as possible after – meningococcal B vaccination and can be followed by two more doses of paracetamol given 6 hours apart, regardless of whether the child has a fever.2

The Australian Immunisation Handbook mentions several strategies to use following vaccination. Immediate aftercare includes strategies such as distracting the infant by immediately changing the infant’s position, such as picking them up and placing them over the parent or caregiver’s shoulder and asking the adult to move around.2

The administration of analgesics or antipyretics following vaccination is rarely required if a child is eating, drinking, playing and happy.13 However, the handbook has recently been updated to include the use of either paracetamol or ibuprofen if a fever of >38.5 oC occurs with associated pain symptoms, or if there is moderate pain at the injection site.2 This pain may be noticed if the infant is unsettled, and cries when the injection site is touched. These can be useful counselling points for parents or caregivers.

It is important to be aware of some of the common issues that arise with using these medicines.6 These include choosing the most appropriate agent to use; understanding the directions for use, including dose and dose-interval; and measuring the correct dose.6 There are also some common myths that parents and caregivers have surrounding the treatment of pain and fever in children that are discussed below.

Ibuprofen or paracetamol are considered first-line agents for pain with or without fever in children.7 For post-vaccination pain/fever in an infant 3 months and older, either agent would be appropriate.7,8

There are some instances where one agent may, however, be preferred over the other. For example, for a child whose pain may be more inflammatory in nature – such as teething, sprain or post-vaccination pain – an anti-inflammatory agent such as ibuprofen may be considered an appropriate choice.7,8

In an infant younger than 3 months of age, paracetamol would be the agent of choice, as ibuprofen is only recommended for use in children aged 3 months and older.

It is important to note that any infant younger than 3 months of age with fever should be referred to a general practitioner (GP).8

There are many caregivers who have been advised at certain times to administer both ibuprofen and paracetamol concurrently or to alternate doses.9,10 This practice is usually not recommended, particularly for mild pain or mild pain associated with fever. Given that many caregivers can struggle with accurately dosing even one medication, recommending using two agents at the same time is not advised,9,11 as complicating things with two agents could compound dose errors.

Two studies have looked at Australian and/or New Zealand caregivers’ skills in being able to determine an appropriate dose of liquid over-the-counter medicines for their child.9,11

Unfortunately, both of these studies highlighted serious flaws in caregivers’ abilities to recommend an appropriate weight-based dose of paracetamol or ibuprofen for their child. Paracetamol should be dosed at 15 mg/kg every 4–6 hours with a maximum of four doses in a 24-hour period.2 Ibuprofen is dosed at 5–10 mg/kg every 6–8 hours with a maximum of three doses in 24 hours recommended.2

One study found almost 1 in 2 caregivers selected an incorrect dose of a liquid medicine (either paracetamol or ibuprofen) in a ‘mock fever scenario’ involving their child, despite the original packaging being available for them to look at.11 More than 4% of the caregivers choosing paracetamol stated they would readminister the medication within 3 hours of the last dose, despite packaging indicating a 4–6-hour dose interval. Almost one-third of the caregivers who selected ibuprofen chose an incorrect dose interval of less than 6 hours.11

Poor knowledge surrounding the dose interval for children’s ibuprofen doses was also found in another study in which two-thirds of caregivers incorrectly believed ibuprofen could be administered up to 4 times a day, instead of the maximum of 3 doses in a 24-hour period when used for a non-prescription dose.10

In the first study, 1 in 6 (16%) caregivers measured a dose that was outside a 10% error margin of the intended dose they stated for their child.11 Another study found similar levels of liquid dosing accuracy, with 1 in 4 (24%) of doses deviating from what parents/caregivers had stated they would give.8 Of these deviations, 13% of doses deviated by more than 20% from the intended dose.9 This study also revealed that caregivers using medicine cups were more likely to measure an inaccurate dose in comparison to using a syringe.9 These findings further support that taking time to show parents/caregivers how to measure accurate doses and use accurate measuring devices is warranted.

Both parents and healthcare providers may have concerns about using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen due to a perceived risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects. However, research consistently shows that when used short term as directed, over-the-counter doses of ibuprofen have a similar tolerability profile in paediatric pain and fever.12,13 Both drugs are associated with a low risk of gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events in patients without contraindications or precautions.12,13

A common misconception is that ibuprofen must be taken with food to minimise GI adverse effects. However, the evidence suggests that for over-the-counter doses of ibuprofen, there is no need to take doses with food, as they are well-tolerated regardless of when the dose is given, and food may even slightly delay gastric absorption. This is true even for children’s dosing.12

Finally, many people believe that an appropriate way to manage fever in children is to place the child in a cold or tepid bath or sponge them in cold water.6 Unfortunately, this practice can in fact make children very uncomfortable and cause them to shiver, which in turn can drive temperatures higher.6 Rather, guidelines recommend dressing children in enough clothing, so they are not too hot or cold. If they are shivering, it is recommended to add another layer of clothing or a blanket until they stop. A face washer or sponge soaked in warm water may be used to also keep them comfortable.6

Routine childhood vaccinations can sometimes be associated with mild adverse effects. Understanding how non-pharmacological strategies and medicines are used to treat pain or fever episodes in this patient cohort is essential in the delivery of evidence-based care by pharmacists. Pharmacists can further support parents and caregivers by addressing misconceptions related to medicines administration around the time of vaccination.

Case scenario continuedYou explain to the Soe family that should Edwin develop a mild fever after vaccination, they should keep him hydrated and encourage rest.8 If the fever is making Edwin distressed, then medicine can be given.2 After your consultation with the Soe family, they decide not to dose Edwin prior to his 6-month vaccinations but stay alert for any distress following his shots. They have decided to purchase some ibuprofen this time and explain that, if they do end up using it, they will check his weight first and follow the directions, ensuring to wait at least 6 hours between doses if he needs more than one dose. |

Professor Rebekah Moles FPS, BPharm, DipHospPharm, PhD is a pharmacist and Professor at the Sydney Pharmacy School (University of Sydney).

Vaccine administration should be in accordance with relevant legislation, the Australian Immunisation Handbook, and state-based conditions specific to the vaccine.

[post_title] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [post_excerpt] => Routine childhood vaccinations can sometimes be associated with mild adverse effects. Understanding how non-pharmacological strategies and medicines are used to treat pain or fever episodes in this patient cohort is essential. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => pain-fever-childhood-vaccinations [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-04-11 11:39:54 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-11 01:39:54 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28888 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [title] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/pain-fever-childhood-vaccinations/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 29117 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29071

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-09 14:04:46

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-09 04:04:46

[post_content] => Around 11% of errors reported to PDL are patient identification errors. While not the main source of dispensing error, it’s still significant – and has grown substantially in recent years.

Patient identification is seemingly straightforward. So why does it often go so wrong?

At the Medication Safety and Efficiency Conference held in Sydney from 2–3 April, experts including Jess Hadley, community pharmacist and Professional Officer at PDL, and Peter Guthrey, Senior Pharmacist – Strategic Policy at PSA, highlighted how routine scenarios often mask high-risk situations and shared practical strategies to address them.

What does ‘patient identification’ mean?

The Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care defines patient identification as matching the right patient to the right treatment, procedure and therapy, Ms Hadley said.

[caption id="attachment_29084" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Jess Hadley, community pharmacist and Professional Officer at PDL[/caption]

‘In incidents reported to PDL, it’s usually the direct supply where that might go wrong,’ she told the conference. ‘But we're seeing more and more that it can also be in the documentation.’

That means matching patients with the right record and documentation when care, medication, therapy and other services are provided; and when clinical handover, transfer or discharge documentation is generated.

Patients are predominantly identified in dispensing systems through their:

Jess Hadley, community pharmacist and Professional Officer at PDL[/caption]

‘In incidents reported to PDL, it’s usually the direct supply where that might go wrong,’ she told the conference. ‘But we're seeing more and more that it can also be in the documentation.’

That means matching patients with the right record and documentation when care, medication, therapy and other services are provided; and when clinical handover, transfer or discharge documentation is generated.

Patients are predominantly identified in dispensing systems through their:

Peter Guthrey, Senior Pharmacist – Strategic Policy at PSA[/caption]

Pharmacists today might serve 100–150 patients over an 8-hour shift. And scripts come via many channels, including by email or scanned tokens.

‘A patient may come to the counter and ask that we access their prescriptions through an active scripts list, or they might get us to scan an electronic token from their phone,’ he said.

‘People [also] send electronic tokens to us or prescriptions through third-party apps such as MedAdvisor, which will put this into a digital queue in the pharmacy.’

Pharmacies may also provide medicines to a health facility, such as a residential aged care facility, or send medication to a depot location for supply – including compounded medicines to the patient’s primary pharmacy.

And this is only the patient identification workflows for dispensing prescriptions. There are also other aspects of clinical care – such as administration of medicines, including vaccines and staged supply pharmacotherapy.

‘Sometimes, you actually need to [ask for three identifiers] multiple times,’ Mr Guthrey said. ‘And because we've gone from having a physical prescription, which contains those identifiers, to different things coming in different ways – we need to be more alert to identification challenges.’

Peter Guthrey, Senior Pharmacist – Strategic Policy at PSA[/caption]

Pharmacists today might serve 100–150 patients over an 8-hour shift. And scripts come via many channels, including by email or scanned tokens.

‘A patient may come to the counter and ask that we access their prescriptions through an active scripts list, or they might get us to scan an electronic token from their phone,’ he said.

‘People [also] send electronic tokens to us or prescriptions through third-party apps such as MedAdvisor, which will put this into a digital queue in the pharmacy.’

Pharmacies may also provide medicines to a health facility, such as a residential aged care facility, or send medication to a depot location for supply – including compounded medicines to the patient’s primary pharmacy.

And this is only the patient identification workflows for dispensing prescriptions. There are also other aspects of clinical care – such as administration of medicines, including vaccines and staged supply pharmacotherapy.

‘Sometimes, you actually need to [ask for three identifiers] multiple times,’ Mr Guthrey said. ‘And because we've gone from having a physical prescription, which contains those identifiers, to different things coming in different ways – we need to be more alert to identification challenges.’

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29051

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-07 12:48:30

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-07 02:48:30

[post_content] => Expansive changes have been made to the Therapeutic Guidelines on antibiotics, encompassing over 1,400 drug recommendations.

The first stage targets infections managed in primary care, including patient information and a dosage calculator for aminoglycosides.

A key change impacting pharmacists, GPs and patients is that trimethoprim is no longer the first-line treatment of acute cystitis in non-pregnant adults due to resistance in Escherichia coli (E. coli).

The new treatment guidance for UTI in adults includes:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29029

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-02 12:03:57

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-02 01:03:57

[post_content] => From the United States to Europe, India and Southeast Asia – measles cases have been exploding worldwide.

In Texas, a measles outbreak with more than 500 cases is ravaging the state – leading to the death of an unvaccinated 6-year-old child. In our own backyard, an outbreak is fast developing in Western Australia – with 10 confirmed cases, and counting. Almost 40 measles cases have been confirmed across Australia this year.

The measles mumps rubella (MMR) vaccination rate in Texas among kindergarten-aged children is 94.3% – slightly below the World Health Organization’s 95% target.

Australia’s vaccination rate for all 5-year-olds is lower, sitting at 93.76%

[caption id="attachment_29037" align="alignright" width="267"] Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

So are we headed for Texas territory? Australian Pharmacist sat down with Professor Margie Danchin, group leader of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute’s (MCRI) Vaccine Uptake Group, to find out.

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

So are we headed for Texas territory? Australian Pharmacist sat down with Professor Margie Danchin, group leader of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute’s (MCRI) Vaccine Uptake Group, to find out.

Is Australia at risk of losing control over measles spread?

To really stop measles transmission, a herd immunity threshold between 93–95% coverage is required. But many areas of the country are well below this figure.

This includes the Noosa Hinterland and the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales – where coverage (two doses of the MMR vaccine) only sits between 70–75%, said Prof Danchin.

‘Measles can spread pretty quickly in a low-coverage population,’ she said. ‘There will be local transmission from secondary cases because there just isn't that coverage there to stop it spreading.’

In a population with 70–75% overage, one case could infect approximately 5–8 people, and then each one of those people can infect another 5–8 people. ‘In low-coverage areas, cases need to be quickly isolated to stop transmission occurring, otherwise it can take off like a wildfire – which is exactly what's happened in the US.’

What’s driving the surge in measles cases?

A range of factors, Prof Danchin said. Take the current outbreak in Texas for example.

‘Geopolitics and the views of the current administration about vaccines being a personal choice is having some impact already,’ she said. ‘But it wouldn't be the whole story.’

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine coverage rates for children have decreased globally due to a complex mix of access and acceptance factors – leaving gaps in coverage that can fuel an outbreak.

In Australia, access barriers are the key driver for partially vaccinated children under 5 years, as identified by the MCRI, University of Sydney and National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance’s (NCIRS) Vaccination Insights Project.

‘We measured nationally the main drivers of low vaccine coverage in Australia among partially and totally un-vaccinated children,’ Prof Danchin said.

‘And the strongest drivers for partially vaccinated kids were practical barriers – including not being able to get an appointment with the GP, or not being able to afford the costs associated with vaccination.’

Because many GPs don’t bulk bill anymore, parents are forced to pay gap payments, along with taking time off work, needing to find childcare for other children and possibly transport costs.

‘It's usually practice nurses who administer the vaccines in general practice, and they might not work full time, or only work once a week,’ she said.

In regions such as the Northern Rivers, hesitancy is likely the driving factor, Prof Danchin said.

‘There's a lot more mistrust in vaccines, providers and institutions post-COVID-19. Because the vaccines were under such intense scrutiny, vaccine safety concerns were really amplified in the media,’ she said.

‘At least 10% of the population still have a concern that the MMR vaccine can cause autism, despite 25 years of research that conclusively disproves the link.’

How can pharmacists promote the importance of vaccination?

By clearly communicating the benefits of vaccines while acknowledging the risks of vaccine-related adverse events.

‘We've got to be careful that we don't oversell vaccine safety,’ Prof Danchin said. ‘We need to be clear that tall vaccines have common and expected side effects, and that serious side effects are very rare.’

Given MMR is a live vaccine, patients can expect side effects around 1 week after receiving the vaccine. This can include a fever, coryza and a rash

But the key is communicating the risk-benefit to patients. ‘One in five people who get measles will have to go to hospital, one in 20 will get pneumonia and one in 1,000 will get inflammation of the brain or encephalitis – so the risks associated with contracting measles are high, especially among the most vulnerable such as babies under 1 year or children who have lowered immune systems,’ she said. ‘It is our responsibility to protect everyone in the community, especially those who cant be vaccinated with live vaccines.’

A communication strategy based on respect, listening and motivational interviewing can also help pharmacists understand where a person sits on the vaccine hesitancy spectrum.

‘For example, we need to assess if the parent is a true refuser or are they a bit of a fence sitter?’ Prof Danchin said. ‘Do they just want to partially vaccinate or do they want to vaccinate fully, but just have some questions?’

The next step is to listen to their concerns and validate them, then ask permission to share information and point them to trustworthy sources.

‘If they're not ready, invite them to come back,’ she said. ‘It’s not coercive and should bring people down from that heightened space of wanting to argue or defend themselves to genuinely being more receptive to the information.’

Pharmacists cal also refer to this resource, developed by a team of researchers and clinicians for parents and providers to help everyone have more non-judgmental conversations.

Who is eligible for a catch-up dose?

Anyone who is partially vaccinated. This also includes adults who were born between 1966 and 1992, with the two-dose schedule of the MMR vaccine only being introduced in Australia in 1992.

If patients are unsure about their or their children’s vaccination status, pharmacists can check the Australian Immunisation Register or advise patients to do so.

Different jurisdictions allow pharmacists to administer the MMR vaccine to children of various ages, so pharmacists should check the regulation in their state or territory before offering a catch-up vaccination.

Patients can receive a funded MMR vaccine under the NIP until 19 years of age, Prof Danchin said.

‘We recommend they get a second dose, because one dose of the MMR vaccine only provides about 91–93% protection,’ Prof Danchin said.

‘While people who've had one dose are more likely to get less severe measles, they can still get quite sick.’

How important is vaccination prior to travel?

Ahead of the Easter holiday break, NSW Minister for Health Ryan Park has called on people planning to travel overseas this April to ensure they and their family are fully protected against measles, with large outbreaks currently in many countries including Vietnam and other parts of Southeast Asia.

‘Measles is one of the most infectious diseases there is, and we are concerned about it spreading quickly in under-vaccinated communities,’ he said. ‘Anyone who is not immune is at risk of developing the disease if they are exposed.’

It’s particularly pertinent that both adults and children who are planning to travel are up to date with their two MMR vaccine doses.

‘Pharmacists should ask, “Are your kids up to date? Are you up to date?” And highlight the fact that you can get a catch-up dose, as one dose doesn't give you high enough protection,’ Prof Danchin said.

Pharmacists can advise parents that children under the eligible vaccination age can also receive protection prior to travelling.

‘Infants aged 6–11 months can be offered a free additional dose of the MMR vaccine in Victoria and NSW so they have at least some protection from measles if they're traveling through airports and on planes,’ she said. ‘But they still have to get their 12 and 18 month doses.’

Those who can’t get vaccinated, such as pregnant people or patients who are immunocompromised, can receive human immunoglobulin up to 6 days after an exposure.

‘And those who are not up to date with their MMR vaccine can get a dose within 4 days of an exposure,’ Prof Danchin added.

[post_title] => Is Australia heading for a massive measles outbreak?

[post_excerpt] => There have been two deaths in the southwest US due to measles. Western Australia is facing a fresh outbreak. Are we next?

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => is-australia-heading-for-a-massive-measles-outbreak

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-04-02 15:10:44

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-02 04:10:44

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29029

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Is Australia heading for a massive measles outbreak?

[title] => Is Australia heading for a massive measles outbreak?

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/is-australia-heading-for-a-massive-measles-outbreak/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 29034

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29014

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-31 14:40:50

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-31 03:40:50

[post_content] => Pregabalin is being used far beyond its approved indications. With rising concerns over safety, the focus is shifting to careful, individualised deprescribing strategies.

Gabapentinoids, such as pregabalin and gabapentin, were registered by the Therapeutics Goods Administration (TGA) in the early 2000s for epileptic seizures and neuropathic pain.

But it was when pregabalin (Lyrica) was listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in 2013 for refractory neuropathic pain unable to be controlled by other drugs, that prescribing of the drug really took off.

By the 2018–19 financial year, pregabalin became the sixth most prescribed subsidised drug in Australia, with over 3.5 million PBS subsidised prescriptions issued.

The highest rate of prescribing of pregabalin is for women over 80 years of age, with one in 10 taking the medicine. Yet this cohort of patients is also at high risk due to their susceptibility to adverse effects.

Originally developed as anti-epileptic drugs, it was discovered that gabapentinoids work for some types of neuropathic pain by dampening down nerve transmission, said credentialed pharmacist and pain educator Dr Peter Tenni MPS.

[caption id="attachment_29018" align="alignright" width="335"] Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

‘But over the years, they have been used for all sorts of nerve-related pain, some of which is not neuropathic,’ he said.

Because gabapentinoids are broad-acting drugs, they have other effects – such as reducing anxiety, leading to approval for use in the United Kingdom for this indication.

‘If you have a drug that reduces anxiety, you will feel better – so a lot of people have a subjective improvement,’ Dr Tenni said. ‘But when you ask them about their pain, it’s no better.’

The topic of reduction or cessation frequently elicits a strong reaction from patients.

‘Patients will say, “Oh no, don’t touch the Lyrica. It's working so well for me” – even when they haven’t seen an improvement in their pain,’ he said. ‘The big issue in the last 5–10 years has been dependence on these drugs.’

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

‘But over the years, they have been used for all sorts of nerve-related pain, some of which is not neuropathic,’ he said.

Because gabapentinoids are broad-acting drugs, they have other effects – such as reducing anxiety, leading to approval for use in the United Kingdom for this indication.

‘If you have a drug that reduces anxiety, you will feel better – so a lot of people have a subjective improvement,’ Dr Tenni said. ‘But when you ask them about their pain, it’s no better.’

The topic of reduction or cessation frequently elicits a strong reaction from patients.

‘Patients will say, “Oh no, don’t touch the Lyrica. It's working so well for me” – even when they haven’t seen an improvement in their pain,’ he said. ‘The big issue in the last 5–10 years has been dependence on these drugs.’

What nerve pain conditions does pregabalin actually help?

Only two types of neuropathic pain: diabetic neuropathy and post-herpetic neuralgia have strong evidence for effectiveness, said Dr Tenni.

‘There's also some evidence for fibromyalgia, which is not truly a neuropathic pain,’ he added.

The use of pregabalin for other indications such as non-specific back pain, sciatica or even back pain with neurological features is not evidence based.

‘There's no evidence that pregabalin is any better than placebo for these indications,’ Dr Tenni said.

In fact, around two out of every three prescriptions of pregabalin are for non-valid indications, most commonly for back pain and nerve sensitisation due to chronic pain, Dr Tenni said.

‘Although people feel better, and therefore may be able to tolerate their pain better, it's not actually treating the underlying problems.’

Gabapentinoids also come with a host of unpleasant adverse effects, including:

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

‘So it’s more difficult in terms of withdrawal symptoms to drop from 25 mg to 0 mg than it is to drop from 600 mg to 300 mg.’

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

‘So it’s more difficult in terms of withdrawal symptoms to drop from 25 mg to 0 mg than it is to drop from 600 mg to 300 mg.’

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28888

[post_author] => 10042

[post_date] => 2025-04-11 12:00:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-11 02:00:11

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_28205" align="alignright" width="182"] This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

Mr and Mrs Soe come into your pharmacy pushing young Edwin in his pram. Edwin is due for his 6-month vaccinations and has an appointment at his GP coming up this week. The Soe family want to get ‘the best pain and fever medicine they can, because after Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations he was quite upset and had a little bit of a fever afterwards (38.1 ºC)’.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Active immunisation uses vaccines to stimulate the immune system.1 In turn, after the administration of vaccines that contain one or more immunogens, the immune system can react to a toxin or pathogen more effectively, helping prevent or reduce the severity of disease.1 Vaccines may induce antibody production by B lymphocytes, that can bind specifically to a toxin or pathogen.1 They may also boost numbers of killer cells such as CD8+ T cells to kill infected cells, or they may increase CD4+ T cells to help more efficiently ‘clear out’ infected cells.1

Regardless of each vaccine’s mechanism of action, immunity after active immunisation generally lasts for months to many years.2 How long the immune response lasts depends on the nature of the vaccine, the type of immune response (antibody or T-cell) and host factors.1 Because of this, inducing the desired immune response may require a series of vaccine doses.2

The Australian Immunisation Handbook provides clinical guidelines about using vaccines safely and effectively. It outlines the vaccines recommended for children and adults following an evidence-based approach.2 The National Immunisation Program schedule provides a guide to the recommended vaccines and their schedule (See Table 1).2

Edwin’s parents explain that he has kept up to date with all his vaccines so far and has no other health concerns. His 6-month vaccinations are being given in 3 days’ time. Looking at the vaccination schedule, you note that the upcoming vaccination will include diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP); hepatitis B; polio and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). All these vaccinations are now available in one combined product.3 You also note that for Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations, he likely received two injections as opposed to the one, with pneumococcal also required at that time.2

Reactions to vaccinations are common,2 and may include redness, swelling and soreness at the injection site, and sometimes a low-grade fever (38–38.5 °C).4 These reactions are usually mild and self-limiting.2

It is likely that Edwin’s low-grade fever and discomfort described by his parents after his 4-month injections were in line with the known common adverse effects associated with childhood vaccinations (see Table 2 ).2

According to the Australian Immunisation Handbook, it is not generally recommended to give a child prophylactic doses of paracetamol or ibuprofen prior to, or at the time of most vaccinations.2 In fact, there is some evidence that interfering with the body’s natural immune response may lower the effectiveness of vaccines.5 In a randomised controlled trial published in the Lancet, researchers demonstrated that antibody response was significantly reduced in the group of healthy infants that received prophylactic paracetamol at the time of both the primary and booster vaccinations for DPT, Haemophilus influenzae and pneumococcal.5

The study concluded that ‘although febrile reactions significantly decreased, prophylactic administration of antipyretic drugs at the time of vaccination should not be routinely recommended, since antibody responses to several vaccine antigens were reduced’.5

In contrast to this advice, however, the immunisation guidelines now recommend a dose of paracetamol 30 minutes prior to the administration of a meningococcal B vaccine.2 The vaccination schedule for healthy infants at low risk of disease recommends MenACWY vaccination at 12 months of age.2 For infants at higher risk of disease, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, they are recommended to also have the meningococcal B vaccine at 2, 4, 6 (with specified risk conditions) and 12 months also. These vaccines have been shown to be associated with the AEFIs listed in Table 2.2

Due to these adverse effects, the Australian Immunisation Handbook suggests that an appropriate 15 mg/kg/dose of paracetamol should be administered 30 minutes prior to – or as soon as possible after – meningococcal B vaccination and can be followed by two more doses of paracetamol given 6 hours apart, regardless of whether the child has a fever.2

The Australian Immunisation Handbook mentions several strategies to use following vaccination. Immediate aftercare includes strategies such as distracting the infant by immediately changing the infant’s position, such as picking them up and placing them over the parent or caregiver’s shoulder and asking the adult to move around.2

The administration of analgesics or antipyretics following vaccination is rarely required if a child is eating, drinking, playing and happy.13 However, the handbook has recently been updated to include the use of either paracetamol or ibuprofen if a fever of >38.5 oC occurs with associated pain symptoms, or if there is moderate pain at the injection site.2 This pain may be noticed if the infant is unsettled, and cries when the injection site is touched. These can be useful counselling points for parents or caregivers.

It is important to be aware of some of the common issues that arise with using these medicines.6 These include choosing the most appropriate agent to use; understanding the directions for use, including dose and dose-interval; and measuring the correct dose.6 There are also some common myths that parents and caregivers have surrounding the treatment of pain and fever in children that are discussed below.

Ibuprofen or paracetamol are considered first-line agents for pain with or without fever in children.7 For post-vaccination pain/fever in an infant 3 months and older, either agent would be appropriate.7,8

There are some instances where one agent may, however, be preferred over the other. For example, for a child whose pain may be more inflammatory in nature – such as teething, sprain or post-vaccination pain – an anti-inflammatory agent such as ibuprofen may be considered an appropriate choice.7,8

In an infant younger than 3 months of age, paracetamol would be the agent of choice, as ibuprofen is only recommended for use in children aged 3 months and older.

It is important to note that any infant younger than 3 months of age with fever should be referred to a general practitioner (GP).8

There are many caregivers who have been advised at certain times to administer both ibuprofen and paracetamol concurrently or to alternate doses.9,10 This practice is usually not recommended, particularly for mild pain or mild pain associated with fever. Given that many caregivers can struggle with accurately dosing even one medication, recommending using two agents at the same time is not advised,9,11 as complicating things with two agents could compound dose errors.

Two studies have looked at Australian and/or New Zealand caregivers’ skills in being able to determine an appropriate dose of liquid over-the-counter medicines for their child.9,11

Unfortunately, both of these studies highlighted serious flaws in caregivers’ abilities to recommend an appropriate weight-based dose of paracetamol or ibuprofen for their child. Paracetamol should be dosed at 15 mg/kg every 4–6 hours with a maximum of four doses in a 24-hour period.2 Ibuprofen is dosed at 5–10 mg/kg every 6–8 hours with a maximum of three doses in 24 hours recommended.2

One study found almost 1 in 2 caregivers selected an incorrect dose of a liquid medicine (either paracetamol or ibuprofen) in a ‘mock fever scenario’ involving their child, despite the original packaging being available for them to look at.11 More than 4% of the caregivers choosing paracetamol stated they would readminister the medication within 3 hours of the last dose, despite packaging indicating a 4–6-hour dose interval. Almost one-third of the caregivers who selected ibuprofen chose an incorrect dose interval of less than 6 hours.11

Poor knowledge surrounding the dose interval for children’s ibuprofen doses was also found in another study in which two-thirds of caregivers incorrectly believed ibuprofen could be administered up to 4 times a day, instead of the maximum of 3 doses in a 24-hour period when used for a non-prescription dose.10

In the first study, 1 in 6 (16%) caregivers measured a dose that was outside a 10% error margin of the intended dose they stated for their child.11 Another study found similar levels of liquid dosing accuracy, with 1 in 4 (24%) of doses deviating from what parents/caregivers had stated they would give.8 Of these deviations, 13% of doses deviated by more than 20% from the intended dose.9 This study also revealed that caregivers using medicine cups were more likely to measure an inaccurate dose in comparison to using a syringe.9 These findings further support that taking time to show parents/caregivers how to measure accurate doses and use accurate measuring devices is warranted.

Both parents and healthcare providers may have concerns about using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen due to a perceived risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects. However, research consistently shows that when used short term as directed, over-the-counter doses of ibuprofen have a similar tolerability profile in paediatric pain and fever.12,13 Both drugs are associated with a low risk of gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events in patients without contraindications or precautions.12,13

A common misconception is that ibuprofen must be taken with food to minimise GI adverse effects. However, the evidence suggests that for over-the-counter doses of ibuprofen, there is no need to take doses with food, as they are well-tolerated regardless of when the dose is given, and food may even slightly delay gastric absorption. This is true even for children’s dosing.12

Finally, many people believe that an appropriate way to manage fever in children is to place the child in a cold or tepid bath or sponge them in cold water.6 Unfortunately, this practice can in fact make children very uncomfortable and cause them to shiver, which in turn can drive temperatures higher.6 Rather, guidelines recommend dressing children in enough clothing, so they are not too hot or cold. If they are shivering, it is recommended to add another layer of clothing or a blanket until they stop. A face washer or sponge soaked in warm water may be used to also keep them comfortable.6

Routine childhood vaccinations can sometimes be associated with mild adverse effects. Understanding how non-pharmacological strategies and medicines are used to treat pain or fever episodes in this patient cohort is essential in the delivery of evidence-based care by pharmacists. Pharmacists can further support parents and caregivers by addressing misconceptions related to medicines administration around the time of vaccination.

Case scenario continuedYou explain to the Soe family that should Edwin develop a mild fever after vaccination, they should keep him hydrated and encourage rest.8 If the fever is making Edwin distressed, then medicine can be given.2 After your consultation with the Soe family, they decide not to dose Edwin prior to his 6-month vaccinations but stay alert for any distress following his shots. They have decided to purchase some ibuprofen this time and explain that, if they do end up using it, they will check his weight first and follow the directions, ensuring to wait at least 6 hours between doses if he needs more than one dose. |

Professor Rebekah Moles FPS, BPharm, DipHospPharm, PhD is a pharmacist and Professor at the Sydney Pharmacy School (University of Sydney).

Vaccine administration should be in accordance with relevant legislation, the Australian Immunisation Handbook, and state-based conditions specific to the vaccine.

[post_title] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [post_excerpt] => Routine childhood vaccinations can sometimes be associated with mild adverse effects. Understanding how non-pharmacological strategies and medicines are used to treat pain or fever episodes in this patient cohort is essential. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => pain-fever-childhood-vaccinations [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-04-11 11:39:54 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-11 01:39:54 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28888 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [title] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/pain-fever-childhood-vaccinations/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 29117 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29071

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-09 14:04:46

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-09 04:04:46

[post_content] => Around 11% of errors reported to PDL are patient identification errors. While not the main source of dispensing error, it’s still significant – and has grown substantially in recent years.

Patient identification is seemingly straightforward. So why does it often go so wrong?

At the Medication Safety and Efficiency Conference held in Sydney from 2–3 April, experts including Jess Hadley, community pharmacist and Professional Officer at PDL, and Peter Guthrey, Senior Pharmacist – Strategic Policy at PSA, highlighted how routine scenarios often mask high-risk situations and shared practical strategies to address them.

What does ‘patient identification’ mean?

The Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care defines patient identification as matching the right patient to the right treatment, procedure and therapy, Ms Hadley said.

[caption id="attachment_29084" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Jess Hadley, community pharmacist and Professional Officer at PDL[/caption]

‘In incidents reported to PDL, it’s usually the direct supply where that might go wrong,’ she told the conference. ‘But we're seeing more and more that it can also be in the documentation.’

That means matching patients with the right record and documentation when care, medication, therapy and other services are provided; and when clinical handover, transfer or discharge documentation is generated.

Patients are predominantly identified in dispensing systems through their:

Jess Hadley, community pharmacist and Professional Officer at PDL[/caption]

‘In incidents reported to PDL, it’s usually the direct supply where that might go wrong,’ she told the conference. ‘But we're seeing more and more that it can also be in the documentation.’

That means matching patients with the right record and documentation when care, medication, therapy and other services are provided; and when clinical handover, transfer or discharge documentation is generated.

Patients are predominantly identified in dispensing systems through their:

Peter Guthrey, Senior Pharmacist – Strategic Policy at PSA[/caption]

Pharmacists today might serve 100–150 patients over an 8-hour shift. And scripts come via many channels, including by email or scanned tokens.

‘A patient may come to the counter and ask that we access their prescriptions through an active scripts list, or they might get us to scan an electronic token from their phone,’ he said.

‘People [also] send electronic tokens to us or prescriptions through third-party apps such as MedAdvisor, which will put this into a digital queue in the pharmacy.’

Pharmacies may also provide medicines to a health facility, such as a residential aged care facility, or send medication to a depot location for supply – including compounded medicines to the patient’s primary pharmacy.

And this is only the patient identification workflows for dispensing prescriptions. There are also other aspects of clinical care – such as administration of medicines, including vaccines and staged supply pharmacotherapy.

‘Sometimes, you actually need to [ask for three identifiers] multiple times,’ Mr Guthrey said. ‘And because we've gone from having a physical prescription, which contains those identifiers, to different things coming in different ways – we need to be more alert to identification challenges.’

Peter Guthrey, Senior Pharmacist – Strategic Policy at PSA[/caption]

Pharmacists today might serve 100–150 patients over an 8-hour shift. And scripts come via many channels, including by email or scanned tokens.

‘A patient may come to the counter and ask that we access their prescriptions through an active scripts list, or they might get us to scan an electronic token from their phone,’ he said.

‘People [also] send electronic tokens to us or prescriptions through third-party apps such as MedAdvisor, which will put this into a digital queue in the pharmacy.’

Pharmacies may also provide medicines to a health facility, such as a residential aged care facility, or send medication to a depot location for supply – including compounded medicines to the patient’s primary pharmacy.

And this is only the patient identification workflows for dispensing prescriptions. There are also other aspects of clinical care – such as administration of medicines, including vaccines and staged supply pharmacotherapy.

‘Sometimes, you actually need to [ask for three identifiers] multiple times,’ Mr Guthrey said. ‘And because we've gone from having a physical prescription, which contains those identifiers, to different things coming in different ways – we need to be more alert to identification challenges.’

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29051

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-07 12:48:30

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-07 02:48:30

[post_content] => Expansive changes have been made to the Therapeutic Guidelines on antibiotics, encompassing over 1,400 drug recommendations.

The first stage targets infections managed in primary care, including patient information and a dosage calculator for aminoglycosides.

A key change impacting pharmacists, GPs and patients is that trimethoprim is no longer the first-line treatment of acute cystitis in non-pregnant adults due to resistance in Escherichia coli (E. coli).

The new treatment guidance for UTI in adults includes:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29029

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-02 12:03:57

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-02 01:03:57

[post_content] => From the United States to Europe, India and Southeast Asia – measles cases have been exploding worldwide.

In Texas, a measles outbreak with more than 500 cases is ravaging the state – leading to the death of an unvaccinated 6-year-old child. In our own backyard, an outbreak is fast developing in Western Australia – with 10 confirmed cases, and counting. Almost 40 measles cases have been confirmed across Australia this year.

The measles mumps rubella (MMR) vaccination rate in Texas among kindergarten-aged children is 94.3% – slightly below the World Health Organization’s 95% target.

Australia’s vaccination rate for all 5-year-olds is lower, sitting at 93.76%

[caption id="attachment_29037" align="alignright" width="267"] Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

So are we headed for Texas territory? Australian Pharmacist sat down with Professor Margie Danchin, group leader of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute’s (MCRI) Vaccine Uptake Group, to find out.

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

So are we headed for Texas territory? Australian Pharmacist sat down with Professor Margie Danchin, group leader of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute’s (MCRI) Vaccine Uptake Group, to find out.

Is Australia at risk of losing control over measles spread?

To really stop measles transmission, a herd immunity threshold between 93–95% coverage is required. But many areas of the country are well below this figure.

This includes the Noosa Hinterland and the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales – where coverage (two doses of the MMR vaccine) only sits between 70–75%, said Prof Danchin.

‘Measles can spread pretty quickly in a low-coverage population,’ she said. ‘There will be local transmission from secondary cases because there just isn't that coverage there to stop it spreading.’

In a population with 70–75% overage, one case could infect approximately 5–8 people, and then each one of those people can infect another 5–8 people. ‘In low-coverage areas, cases need to be quickly isolated to stop transmission occurring, otherwise it can take off like a wildfire – which is exactly what's happened in the US.’

What’s driving the surge in measles cases?

A range of factors, Prof Danchin said. Take the current outbreak in Texas for example.

‘Geopolitics and the views of the current administration about vaccines being a personal choice is having some impact already,’ she said. ‘But it wouldn't be the whole story.’

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine coverage rates for children have decreased globally due to a complex mix of access and acceptance factors – leaving gaps in coverage that can fuel an outbreak.

In Australia, access barriers are the key driver for partially vaccinated children under 5 years, as identified by the MCRI, University of Sydney and National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance’s (NCIRS) Vaccination Insights Project.

‘We measured nationally the main drivers of low vaccine coverage in Australia among partially and totally un-vaccinated children,’ Prof Danchin said.

‘And the strongest drivers for partially vaccinated kids were practical barriers – including not being able to get an appointment with the GP, or not being able to afford the costs associated with vaccination.’

Because many GPs don’t bulk bill anymore, parents are forced to pay gap payments, along with taking time off work, needing to find childcare for other children and possibly transport costs.

‘It's usually practice nurses who administer the vaccines in general practice, and they might not work full time, or only work once a week,’ she said.

In regions such as the Northern Rivers, hesitancy is likely the driving factor, Prof Danchin said.

‘There's a lot more mistrust in vaccines, providers and institutions post-COVID-19. Because the vaccines were under such intense scrutiny, vaccine safety concerns were really amplified in the media,’ she said.

‘At least 10% of the population still have a concern that the MMR vaccine can cause autism, despite 25 years of research that conclusively disproves the link.’

How can pharmacists promote the importance of vaccination?

By clearly communicating the benefits of vaccines while acknowledging the risks of vaccine-related adverse events.

‘We've got to be careful that we don't oversell vaccine safety,’ Prof Danchin said. ‘We need to be clear that tall vaccines have common and expected side effects, and that serious side effects are very rare.’

Given MMR is a live vaccine, patients can expect side effects around 1 week after receiving the vaccine. This can include a fever, coryza and a rash

But the key is communicating the risk-benefit to patients. ‘One in five people who get measles will have to go to hospital, one in 20 will get pneumonia and one in 1,000 will get inflammation of the brain or encephalitis – so the risks associated with contracting measles are high, especially among the most vulnerable such as babies under 1 year or children who have lowered immune systems,’ she said. ‘It is our responsibility to protect everyone in the community, especially those who cant be vaccinated with live vaccines.’

A communication strategy based on respect, listening and motivational interviewing can also help pharmacists understand where a person sits on the vaccine hesitancy spectrum.

‘For example, we need to assess if the parent is a true refuser or are they a bit of a fence sitter?’ Prof Danchin said. ‘Do they just want to partially vaccinate or do they want to vaccinate fully, but just have some questions?’

The next step is to listen to their concerns and validate them, then ask permission to share information and point them to trustworthy sources.

‘If they're not ready, invite them to come back,’ she said. ‘It’s not coercive and should bring people down from that heightened space of wanting to argue or defend themselves to genuinely being more receptive to the information.’

Pharmacists cal also refer to this resource, developed by a team of researchers and clinicians for parents and providers to help everyone have more non-judgmental conversations.

Who is eligible for a catch-up dose?

Anyone who is partially vaccinated. This also includes adults who were born between 1966 and 1992, with the two-dose schedule of the MMR vaccine only being introduced in Australia in 1992.

If patients are unsure about their or their children’s vaccination status, pharmacists can check the Australian Immunisation Register or advise patients to do so.

Different jurisdictions allow pharmacists to administer the MMR vaccine to children of various ages, so pharmacists should check the regulation in their state or territory before offering a catch-up vaccination.

Patients can receive a funded MMR vaccine under the NIP until 19 years of age, Prof Danchin said.

‘We recommend they get a second dose, because one dose of the MMR vaccine only provides about 91–93% protection,’ Prof Danchin said.

‘While people who've had one dose are more likely to get less severe measles, they can still get quite sick.’

How important is vaccination prior to travel?

Ahead of the Easter holiday break, NSW Minister for Health Ryan Park has called on people planning to travel overseas this April to ensure they and their family are fully protected against measles, with large outbreaks currently in many countries including Vietnam and other parts of Southeast Asia.

‘Measles is one of the most infectious diseases there is, and we are concerned about it spreading quickly in under-vaccinated communities,’ he said. ‘Anyone who is not immune is at risk of developing the disease if they are exposed.’

It’s particularly pertinent that both adults and children who are planning to travel are up to date with their two MMR vaccine doses.

‘Pharmacists should ask, “Are your kids up to date? Are you up to date?” And highlight the fact that you can get a catch-up dose, as one dose doesn't give you high enough protection,’ Prof Danchin said.

Pharmacists can advise parents that children under the eligible vaccination age can also receive protection prior to travelling.

‘Infants aged 6–11 months can be offered a free additional dose of the MMR vaccine in Victoria and NSW so they have at least some protection from measles if they're traveling through airports and on planes,’ she said. ‘But they still have to get their 12 and 18 month doses.’

Those who can’t get vaccinated, such as pregnant people or patients who are immunocompromised, can receive human immunoglobulin up to 6 days after an exposure.

‘And those who are not up to date with their MMR vaccine can get a dose within 4 days of an exposure,’ Prof Danchin added.

[post_title] => Is Australia heading for a massive measles outbreak?

[post_excerpt] => There have been two deaths in the southwest US due to measles. Western Australia is facing a fresh outbreak. Are we next?

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => is-australia-heading-for-a-massive-measles-outbreak

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-04-02 15:10:44

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-02 04:10:44

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29029

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Is Australia heading for a massive measles outbreak?

[title] => Is Australia heading for a massive measles outbreak?

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/is-australia-heading-for-a-massive-measles-outbreak/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 29034

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29014

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-31 14:40:50

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-31 03:40:50

[post_content] => Pregabalin is being used far beyond its approved indications. With rising concerns over safety, the focus is shifting to careful, individualised deprescribing strategies.

Gabapentinoids, such as pregabalin and gabapentin, were registered by the Therapeutics Goods Administration (TGA) in the early 2000s for epileptic seizures and neuropathic pain.

But it was when pregabalin (Lyrica) was listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in 2013 for refractory neuropathic pain unable to be controlled by other drugs, that prescribing of the drug really took off.

By the 2018–19 financial year, pregabalin became the sixth most prescribed subsidised drug in Australia, with over 3.5 million PBS subsidised prescriptions issued.

The highest rate of prescribing of pregabalin is for women over 80 years of age, with one in 10 taking the medicine. Yet this cohort of patients is also at high risk due to their susceptibility to adverse effects.

Originally developed as anti-epileptic drugs, it was discovered that gabapentinoids work for some types of neuropathic pain by dampening down nerve transmission, said credentialed pharmacist and pain educator Dr Peter Tenni MPS.

[caption id="attachment_29018" align="alignright" width="335"] Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

‘But over the years, they have been used for all sorts of nerve-related pain, some of which is not neuropathic,’ he said.

Because gabapentinoids are broad-acting drugs, they have other effects – such as reducing anxiety, leading to approval for use in the United Kingdom for this indication.

‘If you have a drug that reduces anxiety, you will feel better – so a lot of people have a subjective improvement,’ Dr Tenni said. ‘But when you ask them about their pain, it’s no better.’

The topic of reduction or cessation frequently elicits a strong reaction from patients.

‘Patients will say, “Oh no, don’t touch the Lyrica. It's working so well for me” – even when they haven’t seen an improvement in their pain,’ he said. ‘The big issue in the last 5–10 years has been dependence on these drugs.’

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

‘But over the years, they have been used for all sorts of nerve-related pain, some of which is not neuropathic,’ he said.

Because gabapentinoids are broad-acting drugs, they have other effects – such as reducing anxiety, leading to approval for use in the United Kingdom for this indication.

‘If you have a drug that reduces anxiety, you will feel better – so a lot of people have a subjective improvement,’ Dr Tenni said. ‘But when you ask them about their pain, it’s no better.’

The topic of reduction or cessation frequently elicits a strong reaction from patients.

‘Patients will say, “Oh no, don’t touch the Lyrica. It's working so well for me” – even when they haven’t seen an improvement in their pain,’ he said. ‘The big issue in the last 5–10 years has been dependence on these drugs.’

What nerve pain conditions does pregabalin actually help?

Only two types of neuropathic pain: diabetic neuropathy and post-herpetic neuralgia have strong evidence for effectiveness, said Dr Tenni.

‘There's also some evidence for fibromyalgia, which is not truly a neuropathic pain,’ he added.

The use of pregabalin for other indications such as non-specific back pain, sciatica or even back pain with neurological features is not evidence based.

‘There's no evidence that pregabalin is any better than placebo for these indications,’ Dr Tenni said.

In fact, around two out of every three prescriptions of pregabalin are for non-valid indications, most commonly for back pain and nerve sensitisation due to chronic pain, Dr Tenni said.

‘Although people feel better, and therefore may be able to tolerate their pain better, it's not actually treating the underlying problems.’

Gabapentinoids also come with a host of unpleasant adverse effects, including:

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

‘So it’s more difficult in terms of withdrawal symptoms to drop from 25 mg to 0 mg than it is to drop from 600 mg to 300 mg.’

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

‘So it’s more difficult in terms of withdrawal symptoms to drop from 25 mg to 0 mg than it is to drop from 600 mg to 300 mg.’

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28888

[post_author] => 10042

[post_date] => 2025-04-11 12:00:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-11 02:00:11

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_28205" align="alignright" width="182"] This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

Mr and Mrs Soe come into your pharmacy pushing young Edwin in his pram. Edwin is due for his 6-month vaccinations and has an appointment at his GP coming up this week. The Soe family want to get ‘the best pain and fever medicine they can, because after Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations he was quite upset and had a little bit of a fever afterwards (38.1 ºC)’.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Active immunisation uses vaccines to stimulate the immune system.1 In turn, after the administration of vaccines that contain one or more immunogens, the immune system can react to a toxin or pathogen more effectively, helping prevent or reduce the severity of disease.1 Vaccines may induce antibody production by B lymphocytes, that can bind specifically to a toxin or pathogen.1 They may also boost numbers of killer cells such as CD8+ T cells to kill infected cells, or they may increase CD4+ T cells to help more efficiently ‘clear out’ infected cells.1

Regardless of each vaccine’s mechanism of action, immunity after active immunisation generally lasts for months to many years.2 How long the immune response lasts depends on the nature of the vaccine, the type of immune response (antibody or T-cell) and host factors.1 Because of this, inducing the desired immune response may require a series of vaccine doses.2

The Australian Immunisation Handbook provides clinical guidelines about using vaccines safely and effectively. It outlines the vaccines recommended for children and adults following an evidence-based approach.2 The National Immunisation Program schedule provides a guide to the recommended vaccines and their schedule (See Table 1).2

Edwin’s parents explain that he has kept up to date with all his vaccines so far and has no other health concerns. His 6-month vaccinations are being given in 3 days’ time. Looking at the vaccination schedule, you note that the upcoming vaccination will include diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP); hepatitis B; polio and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). All these vaccinations are now available in one combined product.3 You also note that for Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations, he likely received two injections as opposed to the one, with pneumococcal also required at that time.2

Reactions to vaccinations are common,2 and may include redness, swelling and soreness at the injection site, and sometimes a low-grade fever (38–38.5 °C).4 These reactions are usually mild and self-limiting.2

It is likely that Edwin’s low-grade fever and discomfort described by his parents after his 4-month injections were in line with the known common adverse effects associated with childhood vaccinations (see Table 2 ).2

According to the Australian Immunisation Handbook, it is not generally recommended to give a child prophylactic doses of paracetamol or ibuprofen prior to, or at the time of most vaccinations.2 In fact, there is some evidence that interfering with the body’s natural immune response may lower the effectiveness of vaccines.5 In a randomised controlled trial published in the Lancet, researchers demonstrated that antibody response was significantly reduced in the group of healthy infants that received prophylactic paracetamol at the time of both the primary and booster vaccinations for DPT, Haemophilus influenzae and pneumococcal.5

The study concluded that ‘although febrile reactions significantly decreased, prophylactic administration of antipyretic drugs at the time of vaccination should not be routinely recommended, since antibody responses to several vaccine antigens were reduced’.5

In contrast to this advice, however, the immunisation guidelines now recommend a dose of paracetamol 30 minutes prior to the administration of a meningococcal B vaccine.2 The vaccination schedule for healthy infants at low risk of disease recommends MenACWY vaccination at 12 months of age.2 For infants at higher risk of disease, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, they are recommended to also have the meningococcal B vaccine at 2, 4, 6 (with specified risk conditions) and 12 months also. These vaccines have been shown to be associated with the AEFIs listed in Table 2.2

Due to these adverse effects, the Australian Immunisation Handbook suggests that an appropriate 15 mg/kg/dose of paracetamol should be administered 30 minutes prior to – or as soon as possible after – meningococcal B vaccination and can be followed by two more doses of paracetamol given 6 hours apart, regardless of whether the child has a fever.2

The Australian Immunisation Handbook mentions several strategies to use following vaccination. Immediate aftercare includes strategies such as distracting the infant by immediately changing the infant’s position, such as picking them up and placing them over the parent or caregiver’s shoulder and asking the adult to move around.2

The administration of analgesics or antipyretics following vaccination is rarely required if a child is eating, drinking, playing and happy.13 However, the handbook has recently been updated to include the use of either paracetamol or ibuprofen if a fever of >38.5 oC occurs with associated pain symptoms, or if there is moderate pain at the injection site.2 This pain may be noticed if the infant is unsettled, and cries when the injection site is touched. These can be useful counselling points for parents or caregivers.

It is important to be aware of some of the common issues that arise with using these medicines.6 These include choosing the most appropriate agent to use; understanding the directions for use, including dose and dose-interval; and measuring the correct dose.6 There are also some common myths that parents and caregivers have surrounding the treatment of pain and fever in children that are discussed below.

Ibuprofen or paracetamol are considered first-line agents for pain with or without fever in children.7 For post-vaccination pain/fever in an infant 3 months and older, either agent would be appropriate.7,8

There are some instances where one agent may, however, be preferred over the other. For example, for a child whose pain may be more inflammatory in nature – such as teething, sprain or post-vaccination pain – an anti-inflammatory agent such as ibuprofen may be considered an appropriate choice.7,8

In an infant younger than 3 months of age, paracetamol would be the agent of choice, as ibuprofen is only recommended for use in children aged 3 months and older.

It is important to note that any infant younger than 3 months of age with fever should be referred to a general practitioner (GP).8

There are many caregivers who have been advised at certain times to administer both ibuprofen and paracetamol concurrently or to alternate doses.9,10 This practice is usually not recommended, particularly for mild pain or mild pain associated with fever. Given that many caregivers can struggle with accurately dosing even one medication, recommending using two agents at the same time is not advised,9,11 as complicating things with two agents could compound dose errors.

Two studies have looked at Australian and/or New Zealand caregivers’ skills in being able to determine an appropriate dose of liquid over-the-counter medicines for their child.9,11

Unfortunately, both of these studies highlighted serious flaws in caregivers’ abilities to recommend an appropriate weight-based dose of paracetamol or ibuprofen for their child. Paracetamol should be dosed at 15 mg/kg every 4–6 hours with a maximum of four doses in a 24-hour period.2 Ibuprofen is dosed at 5–10 mg/kg every 6–8 hours with a maximum of three doses in 24 hours recommended.2

One study found almost 1 in 2 caregivers selected an incorrect dose of a liquid medicine (either paracetamol or ibuprofen) in a ‘mock fever scenario’ involving their child, despite the original packaging being available for them to look at.11 More than 4% of the caregivers choosing paracetamol stated they would readminister the medication within 3 hours of the last dose, despite packaging indicating a 4–6-hour dose interval. Almost one-third of the caregivers who selected ibuprofen chose an incorrect dose interval of less than 6 hours.11

Poor knowledge surrounding the dose interval for children’s ibuprofen doses was also found in another study in which two-thirds of caregivers incorrectly believed ibuprofen could be administered up to 4 times a day, instead of the maximum of 3 doses in a 24-hour period when used for a non-prescription dose.10

In the first study, 1 in 6 (16%) caregivers measured a dose that was outside a 10% error margin of the intended dose they stated for their child.11 Another study found similar levels of liquid dosing accuracy, with 1 in 4 (24%) of doses deviating from what parents/caregivers had stated they would give.8 Of these deviations, 13% of doses deviated by more than 20% from the intended dose.9 This study also revealed that caregivers using medicine cups were more likely to measure an inaccurate dose in comparison to using a syringe.9 These findings further support that taking time to show parents/caregivers how to measure accurate doses and use accurate measuring devices is warranted.