td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29172

[post_author] => 250

[post_date] => 2025-04-16 15:41:17

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-16 05:41:17

[post_content] => The Fair Work Commission’s Expert Panel for pay equity in the care and community sector has today issued its initial decision on the Gender-based undervaluation – priority awards review – making determinations on the Pharmacy Industry Award 2020, which most community pharmacists are employed under.

What did the Expert Panel find?

The Expert Panel found that pharmacists covered by the Pharmacy Industry Award 2020 (and several other awards) have been the subject of gender-based undervaluation.

As a result, the Expert Panel has determined that findings constitute work value reasons, justifying variation of the modern award minimum wage rates across all categories of pharmacists.

What is ‘gender-based undervaluation’?

Gender-based undervaluation considers a range of factors to determine whether minimum award pay rates are undervalued because of assumptions based on gender.

The range of factors considered extends to historical undervaluing, exercise of ‘invisible skills’, exercise of caring work and workforce qualifications, among others.

How does the Expert Panel intend to address the undervaluation?

For pharmacists employed by the Pharmacy Industry Award 2020, the Expert Panel has issued a determination that there will be a total increase in the minimum wage rates of 14.1% over three years.

This increase will be implemented in three equal phases on:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28725

[post_author] => 10075

[post_date] => 2025-04-16 10:13:21

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-16 00:13:21

[post_content] => Case scenario

Malcolm (68 years old, male) visits your pharmacy with a new prescription for sacubitril/valsartan. He mentions he has recently been diagnosed with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). You review his records and confirm he is still taking metformin/sitagliptin for type 2 diabetes. Malcolm explains that he has taken this for many years, and that his general practitioner has advised him that his blood glucose control needs to be better. He expresses frustration that the shortness of breath from his heart failure limits his ability to exercise and improve his diabetes. Malcolm hopes that starting this new medicine will improve this.

After reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Already read the CPD in the journal? Scroll to the bottom to SUBMIT ANSWERS.

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome caused by the inability of the heart muscle to provide adequate cardiac output and/or the presence of increased cardiac pressure. This is due to either a structural or functional abnormality of the heart.1 The clinical syndrome consists of symptoms such as breathlessness and fatigue and may be accompanied by signs of fluid accumulation such as peripheral oedema, elevated jugular venous pressure and pulmonary crackles.1

In many cases, heart failure may be both preventable and treatable. Choice of treatment depends on the type of heart failure present, with management being primarily pharmacological.1

Pharmacists play an essential role in optimising pharmacotherapy for heart failure patients, providing recommendations on safe and effective dose titration and appropriate pharmacological management, as well as providing education, counselling and support for adherence.2

Heart failure remains a global public health issue that affects at least 38 million people worldwide.2 It is a major cause of hospitalisation in Australia and is associated with significant healthcare costs.3

Heart failure has a poor prognosis and results in markedly reduced quality of life.1 Readmission to hospital is extremely common, with about 1 in 3 patients being readmitted in the first month, and up to 15% of patients dying within the first 6 months, after being discharged from hospital.4 By 12 months post-discharge, approximately 25% of heart failure patients will have died.5

Concerningly, due to population aging and increasing prevalence of comorbidities, heart failure hospitalisations could increase by as much as 50% in the next 25 years.1

Categorisation of heart failure

Categorisation of heart failureHeart failure is categorised according to the measurement of the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Knowing the LVEF at time of diagnosis is crucial, as this guides treatment.1 Heart failure is categorised as either1,6,7:

HFrEF

For HFrEF, there are effective pharmacological therapies, supported by robust, high-quality evidence. These include what has now become known as ‘the four pillars’, and these collectively make up guideline-directed medical therapy for HFrEF. These include9–11:

All patients with HFrEF should be prescribed all four agents (unless contraindicated or not tolerated), with early initiation being associated with the best outcomes.1,9,10 Other therapies are available as HFrEF progresses, however the ‘four pillars’ are the cornerstone of HFrEF treatment.10

HFmrEF

There is limited evidence to support specific recommendations for the pharmacological management of HFmrEF.1 Some studies suggest that patients with HFmrEF may receive similar benefit from a beta blocker, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and a renin angiotensin system inhibitor as in HFrEF, and SGLT2is have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalisation for heart failure.14 The medicines used to treat HFrEF are often used to treat HFmrEF, however the confidence in prognostic benefits is much less.1,14

HFpEF

For the treatment of HFpEF, no medicines have demonstrated a statistically significant benefit on mortality.1 Recommended treatment consists of15:

The use of an SGLT2i in HFpEF has not been shown to improve mortality to the same extent as for HFrEF. However, an SGLT2i is still recommended because major trials have shown they can still offer some benefits.16,17

The EMPEROR-Preserved trial demonstrated a 21% lower relative risk in the composite of cardiovascular death or hospitalisation for heart failure with the use of empagliflozin in the treatment of HFpEF compared with placebo – a result driven primarily by a reduction in risk of hospitalisation rather than mortality.16 Importantly, this benefit was seen regardless of the diabetic status of the patient.16 This benefit was later reinforced by the DELIVER trial which showed a lower risk of its composite primary outcome of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death with dapagliflozin use, compared to placebo for those with HFmrEF and HFpEF.18 As a result, SGLT2is have received a strong recommendation for the management of HFpEF in treatment guidelines.1

Additionally, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists are used in clinical practice because they have been associated with a reduction in risk of hospitalisation for HFpEF patients, as demonstrated by the TOPCAT trial.19

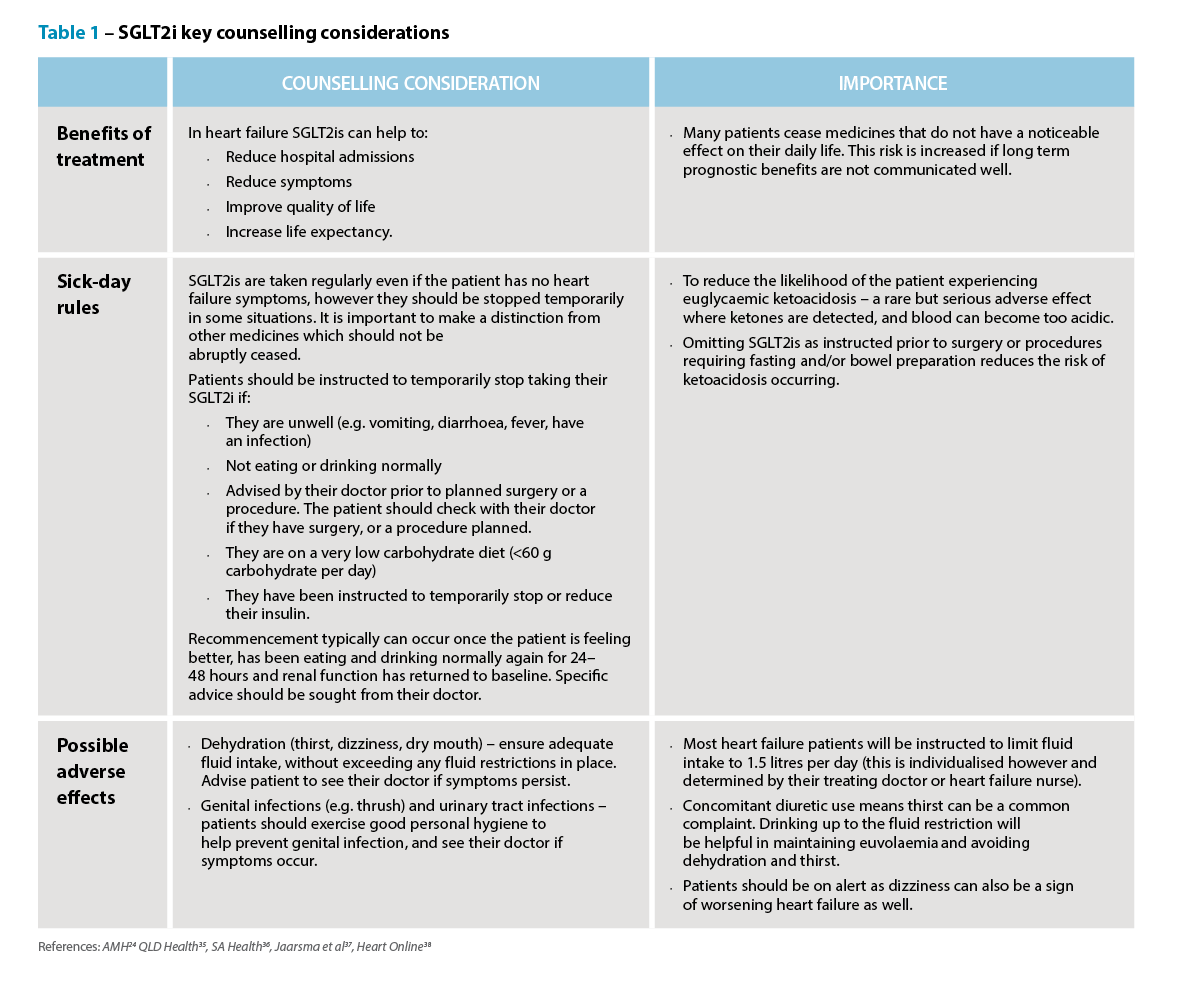

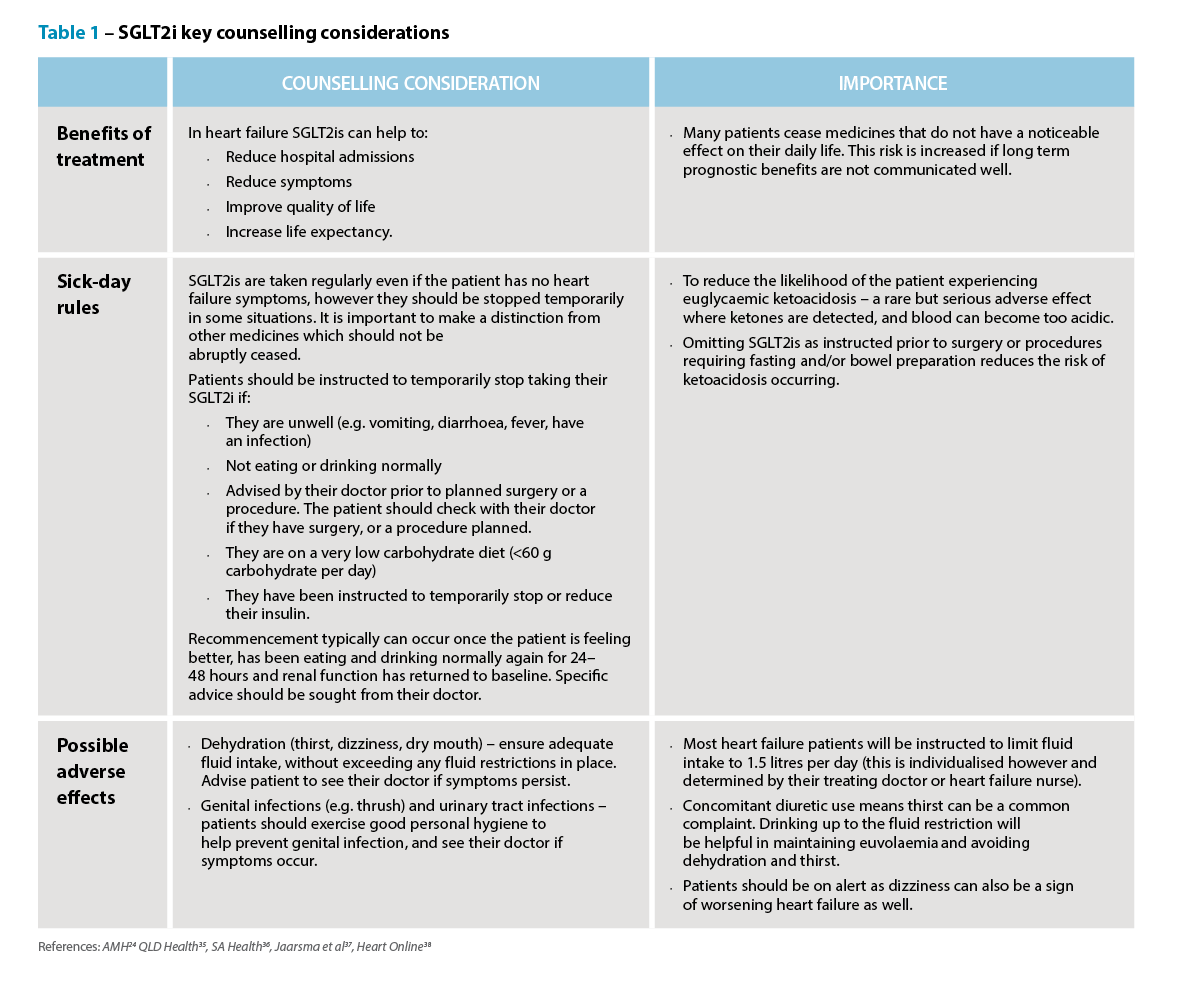

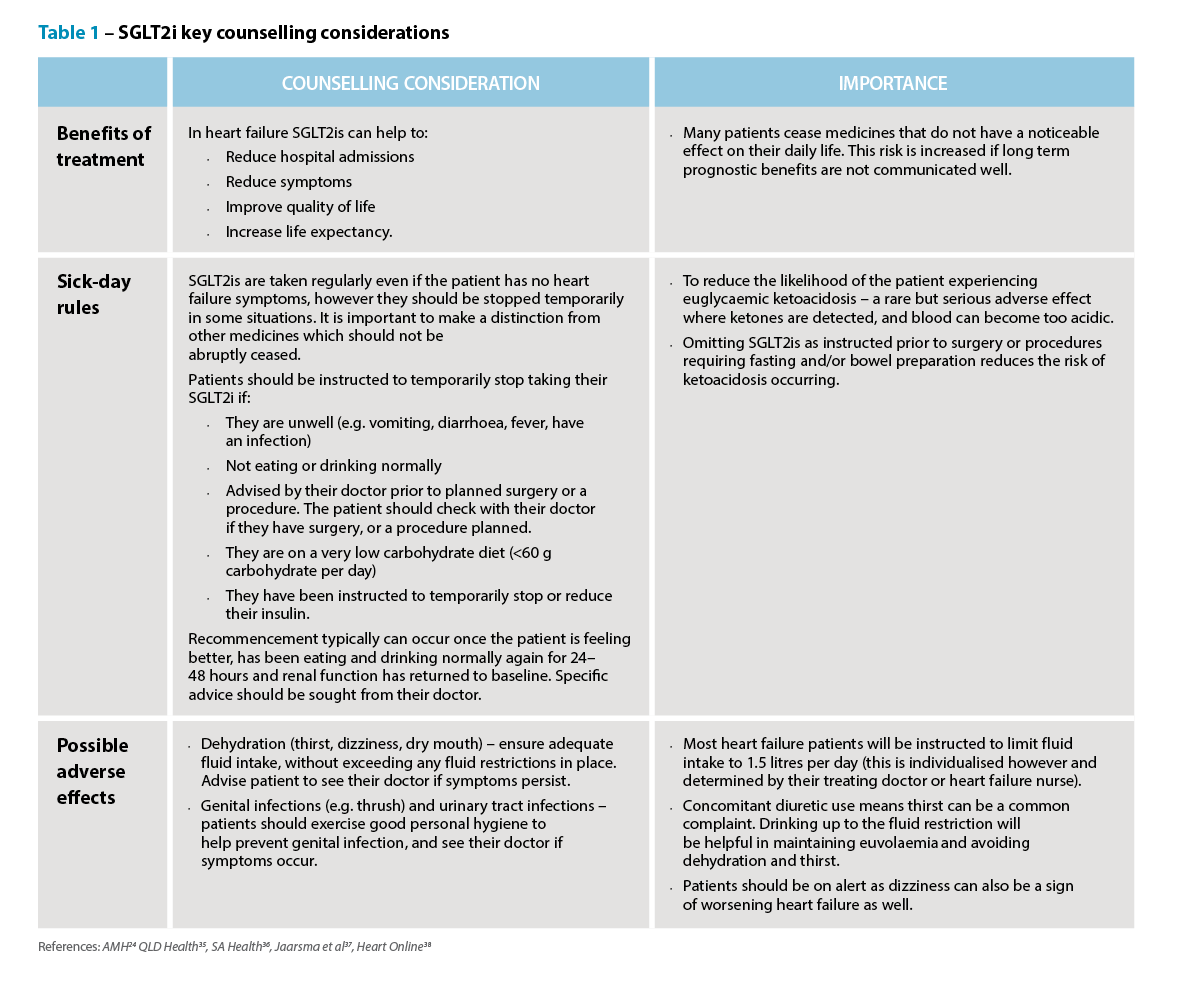

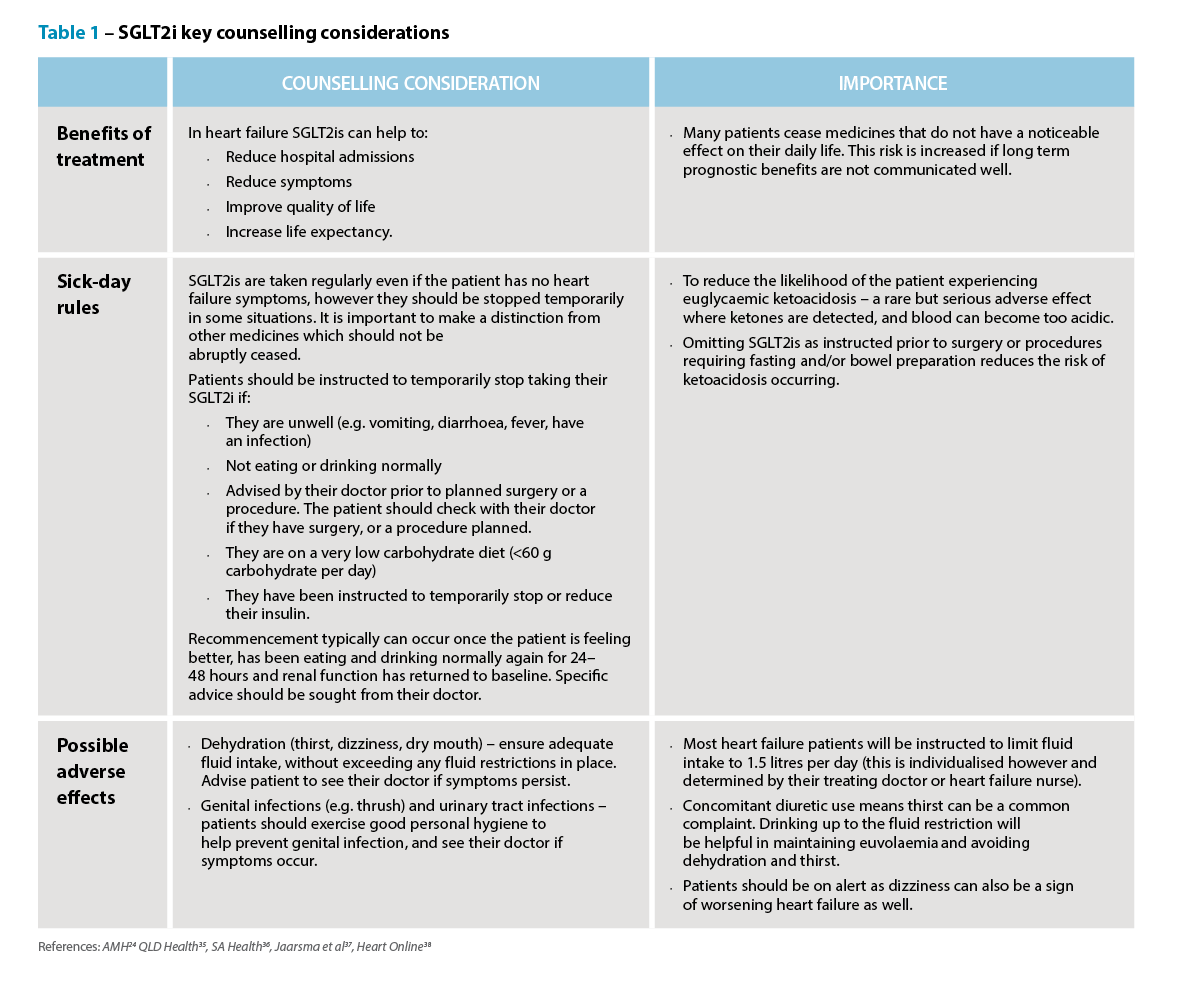

A focus on SGLT2is

A focus on SGLT2isInitially developed as a medicine used for type 2 diabetes, SGLT2is have become a crucial cardiovascular drug class, as demonstrated above by their role in the management of heart failure, and now have renal and cardiovascular indications irrespective of type 2 diabetic status. This is largely due to results of cardiovascular outcome trials mandated by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008. These trials led to findings that have significantly changed clinical practice.20 They arose from concerns of cardiovascular risks with certain medicines used for type 2 diabetes, evidence suggesting rosiglitazone may increase the risk of myocardial infarction, and in recognition of the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in these patients.20

SGLT2is lower blood glucose by inhibiting SGLT2 transporters in the proximal tubules of the kidneys to decrease glucose reabsorption, which increases the excretion of glucose in the urine.21 Sodium excretion also occurs because the SGLT2 receptor is close to, and works together with, a sodium/hydrogen exchanger, which is a major receptor responsible for sodium reuptake.22

Although SGLT2is lower blood glucose, blood pressure and contribute to diuresis, their benefits in terms of renal and cardiovascular outcomes cannot be solely attributed to these properties, as similar clinical benefits are not seen with other agents that lower glucose, blood pressure or increase natriuresis to similar or greater extent.23,24 The mechanism of action linked to these benefits is complex, and appears to also be a combination of anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects, a reduction in epicardial fat and a reduction in hyperinsulinaemia.21

Additional evidence also suggests a reduction in oxidative stress, less coronary microvascular injury and improved contractile performance.23 Emerging clinical evidence may also suggest antiarrhythmic properties, which is particularly important given that ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death is a major cause of death in heart failure patients.21 Some trials have demonstrated a decrease in sudden cardiac death for patients using a SGLT2i.21

The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial in 2015 was a landmark study, demonstrating that empagliflozin significantly reduced cardiovascular death among high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes, compared to placebo.25 Importantly, it also suggested renal benefits, with less cases of acute renal failure in the empagliflozin group.25 These findings were later confirmed by the EMPA-Kidney (empagliflozin) and DAPA-CKD (dapagliflozin) trials, which both showed reduced rates of death due to renal disease, slower decline in renal function and delayed time to needing dialysis.26–28

The cardiovascular benefits of these medicines went on to be confirmed in further trials including the DAPA-HF (2019), EMPEROR Reduced (2020), EMPEROR Preserved (2021) and DELIVER (2022) trials.16,18,29,30

Key practice points

Knowledge to practice

Knowledge to practice The use of heart failure guideline-directed medical therapy in HFrEF can have a significant impact on patient outcomes. The combination of the ‘four pillars’ (a heart failure beta blocker, an mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, a renin angiotensin system inhibitor and an SGLT2i) has the ability to improve life expectancy, delay disease progression, decrease heart failure symptoms and improve quality of life.9,10 All patients with HFrEF should be prescribed all four agents unless a contraindication or intolerance exists preventing their use.32

In HFpEF, there are currently no medicines that demonstrate a statistically significant benefit on mortality. However, the use of SGLT2is has been shown to reduce risk of hospitalisation (regardless of diabetic status) and are recommended to be used by guidelines as part of its management, and in the managment of HFmrEF.1,9,14

Heart failure remains a significant health burden, but modern medicines, particularly SGLT2is, can offer significant benefits. Pharmacists play a pivotal role in optimising therapy, ensuring adherence, and providing education to patients. By leveraging their expertise as medication experts, pharmacists can profoundly impact outcomes, improving survival and quality of life for individuals living with heart failure and associated comorbidities.

Case scenario continuedRecognising the benefits of an SGLT2i for both Malcolm’s heart failure and diabetes, you discuss the option of adding an SGLT2i to his regimen, and the potential benefits and risks. Malcolm explains that his main priority is to get his heart failure symptoms under control so that he can play with his grandchildren and exercise comfortably. At Malcolm’s request, you contact his GP, and it is agreed to commence empagliflozin 10 mg daily (after ensuring his eGFR is appropriate). This intervention may help to reduce Malcolm’s risk of death from heart failure, improve his quality of life, delay disease progression, improve diabetic control and assist in helping him achieve his health goals. |

[cpd_submit_answer_button]

Cassie Potts (she/her) BPharm, GradCertChronCondMgt, FANZCAP (Cardiol), AdPhaM is a Senior Clinical Pharmacist with SA Pharmacy and has over 11 years of experience specialising in heart failure as part of the cardiology team at Flinders Medical Centre. She serves on the AdPha Cardiology Leadership Committee and currently practises within the intensive care unit at the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

Hana Numan (she/her) BPharm (NZ), PGDipClinPharm (NZ), MPS (NZ)

[post_title] => SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure [post_excerpt] => Heart failure remains a significant health burden, but modern medicines, particularly SGLT2is, can offer significant benefits. Pharmacists play a pivotal role in optimising therapy, ensuring adherence, and providing education to patients. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => sglt2-inhibitors-in-heart-failure [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-04-16 15:42:24 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-16 05:42:24 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28725 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure [title] => SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/sglt2-inhibitors-in-heart-failure/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 29161 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29133

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-14 16:21:01

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-14 06:21:01

[post_content] => Data shows that while community pharmacists have smashed previous early-season influenza vaccination records, national coverage still lags dangerously.

Australia is experiencing its worst start to an influenza season, with case numbers surging and vaccination rates falling behind across key age groups.

Amid early peaks, a rise in influenza B cases, and sluggish immunisation uptake, Australian Pharmacist presents a visual snapshot of how the 2025 flu season is unfolding – and what must be done now to prevent a looming public health crisis.

1. Influenza case numbers have reached unprecedented levels to start 2025

This year, influenza cases have reached their highest level in almost a quarter of a century (24 years). To date, there have been 58,203 notifications of laboratory-confirmed influenza reported to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) – with 2025 Quarter One case reports dwarfing that of previous years.

The flu season started earlier than usual this year, with cases surging sooner than in previous years. Early peaks often lead to higher overall case numbers – particularly when coupled with low immunisation rates.

In 2025, there has been a higher proportion of influenza B cases than in previous years, particularly in school-aged children and young adults, said Professor Anthony Lawler, Australian Government Chief Medical Officer. ‘Influenza B is often more common in children, and can result in more severe infections in children,’ he said.

[caption id="attachment_29144" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Professor Anthony Lawler, Australian Government Chief Medical Officer, got his 2025 vaccine at a Canberra community pharmacy[/caption]

With the northern hemisphere experiencing a severe influenza season, and strains in this region typically migrating south, Rural Doctors Association of Victoria president Louise Manning said the trend was ‘worrying’.

‘We're quite concerned that, given the severity of symptoms and the number of hospitalisations in the northern hemisphere in their winter, that we'll have a similar picture here,’ Dr Manning told the ABC.

Professor Anthony Lawler, Australian Government Chief Medical Officer, got his 2025 vaccine at a Canberra community pharmacy[/caption]

With the northern hemisphere experiencing a severe influenza season, and strains in this region typically migrating south, Rural Doctors Association of Victoria president Louise Manning said the trend was ‘worrying’.

‘We're quite concerned that, given the severity of symptoms and the number of hospitalisations in the northern hemisphere in their winter, that we'll have a similar picture here,’ Dr Manning told the ABC.

2. Pharmacists have had a fast start to influenza vaccination

Data over the last 4 years shows pharmacist-administered vaccines are experiencing continued growth.

Key factors influencing this growth include increased trust in the pharmacy profession to administer vaccines as well as accessibility. With longer operating hours – including evenings and weekends – pharmacies offer greater accessibility, allowing patients to receive influenza vaccinations without appointments or extended wait times. This convenience factor makes pharmacy a more flexible alternative to traditional healthcare settings such as General Practice.

3. Vaccination rates are far too low in children under 5

When it comes to influenza, children aged 0–5 are one of the most vulnerable cohorts – with the high risk of severe complications sometimes leading to hospitalisations, often due to pneumonia, and death.

Despite the risks, vaccination rates remain low in this age cohort, with only 7,398 children aged 0–5 receiving the influenza vaccine so far this year.

Despite the influenza vaccine being covered under the National Immunisation Program for this age group, less than half (45%) of parents are aware that their child can be vaccinated free of charge.

In 2024, only 25.8% of children 6 months to 4 years received an influenza vaccine – with three quarters of this at risk population remaining unvaccinated.

Many parents believe that influenza is not a serious disease or that the vaccine is ineffective or unsafe, with 29% exposed to misinformation and 26% influenced by anti-vaccine sentiment through social media.

Vaccine access can also prove challenging. To boost participation in young children, PSA maintains that there should be ‘no wrong door’ when it comes to vaccination – meaning pharmacists should be able to provide influenza vaccines alongside other childhood immunisations, said Chris Campbell MPS, PSA General Manager Policy and Program Delivery.

‘What [this] does do is increase the convenience for someone to be able to get the vaccine at a time and place of their choosing,’ he said.

‘There should be an increase in vaccine uptake in children under 5 years of age when there’s an opportunity for an entire family to come to the pharmacy and get vaccinated.’

4. Vaccination rates in all cohorts need to improve to stave off a devastating influenza season

The latest data on influenza vaccination coverage in Australia for 2025 reveals concerningly low uptake across all age groups and jurisdictions. Western Australia, Tasmania, and Victoria report particularly low figures at this stage among children 6 months to >5 years and aged 5 to under 15 years, with some states showing uptake as low as 0.1%.

Among patients aged 50 to under 65 years, national coverage sits at 2.8%, with Queensland (4.5%) and South Australia (4.0%) leading the charge. Coverage increases more significantly in the over 65s demographic – with South Australia (14.2%) and Queensland (12.6%) again topping vaccination coverage.

Vaccine manufacturers are also expecting a surge in cases, with CSLSeqirus revealing it has boosted its vaccine output by 100,000 doses this season.

To protect the community from a particularly nasty influenza season, experts have urged people to roll up their sleeves and get vaccinated.

‘If you don't want to get crook get vaccinated,’ Public Health Association of Australia chief executive Terry Slevin said.

‘You're less likely to get crook and if you do get crook, you'll be crook for a shorter period of time ... and reduce the misery.’

[post_title] => Flu cases surge to record highs as vaccination rates stall

[post_excerpt] => While community pharmacists have smashed previous early-season influenza vaccination records, national coverage still lags dangerously.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => flu-cases-surge-to-record-highs-as-vaccination-rates-stall

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

https://www.immunisationcoalition.org.au/australia-sees-record-breaking-influenza-season-amid-declining-vaccination-rates/

[post_modified] => 2025-04-14 18:14:43

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-14 08:14:43

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29133

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Flu cases surge to record highs as vaccination rates stall

[title] => Flu cases surge to record highs as vaccination rates stall

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/flu-cases-surge-to-record-highs-as-vaccination-rates-stall/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 29148

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28888

[post_author] => 10042

[post_date] => 2025-04-11 12:00:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-11 02:00:11

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_28205" align="alignright" width="182"] This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

Mr and Mrs Soe come into your pharmacy pushing young Edwin in his pram. Edwin is due for his 6-month vaccinations and has an appointment at his GP coming up this week. The Soe family want to get ‘the best pain and fever medicine they can, because after Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations he was quite upset and had a little bit of a fever afterwards (38.1 ºC)’.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Active immunisation uses vaccines to stimulate the immune system.1 In turn, after the administration of vaccines that contain one or more immunogens, the immune system can react to a toxin or pathogen more effectively, helping prevent or reduce the severity of disease.1 Vaccines may induce antibody production by B lymphocytes, that can bind specifically to a toxin or pathogen.1 They may also boost numbers of killer cells such as CD8+ T cells to kill infected cells, or they may increase CD4+ T cells to help more efficiently ‘clear out’ infected cells.1

Regardless of each vaccine’s mechanism of action, immunity after active immunisation generally lasts for months to many years.2 How long the immune response lasts depends on the nature of the vaccine, the type of immune response (antibody or T-cell) and host factors.1 Because of this, inducing the desired immune response may require a series of vaccine doses.2

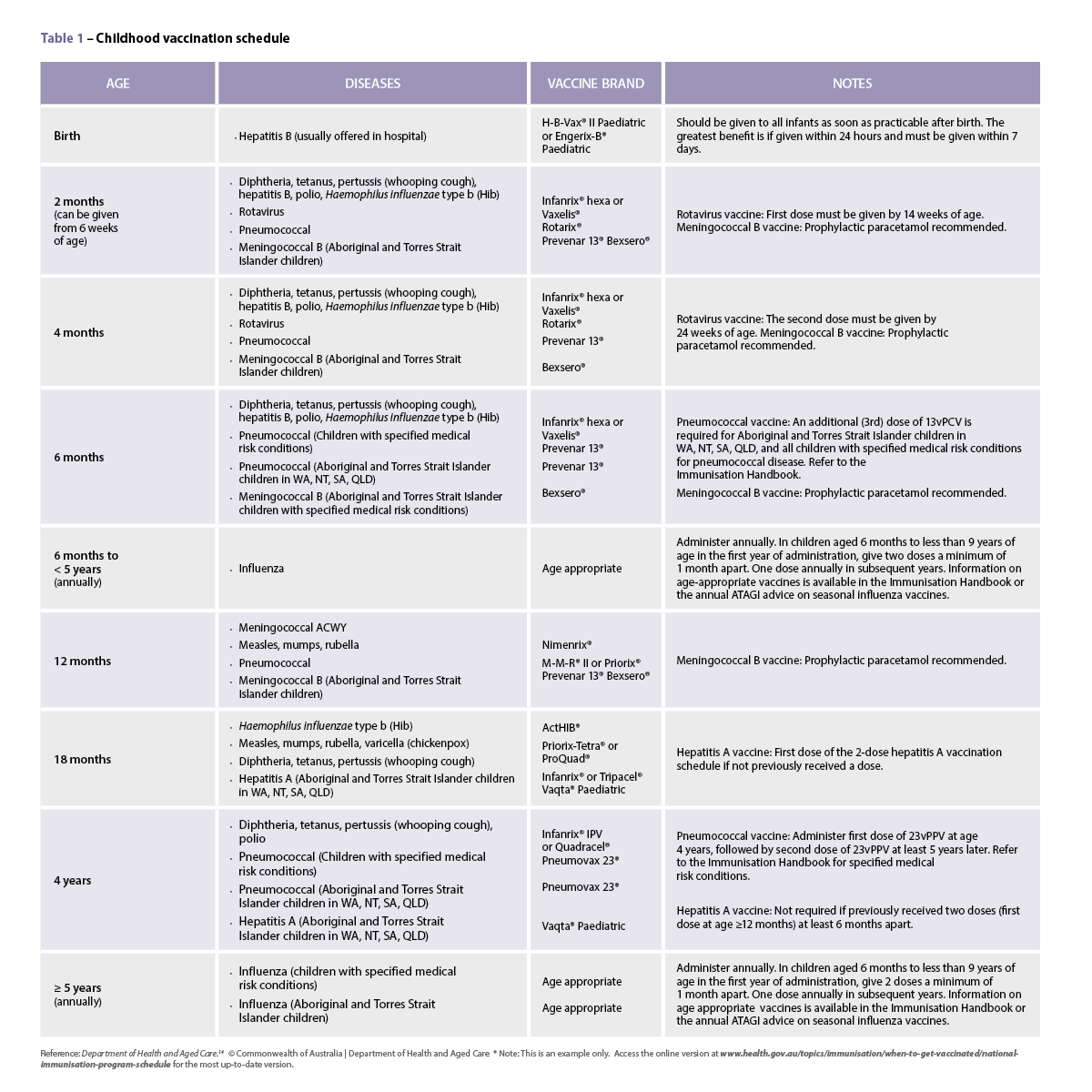

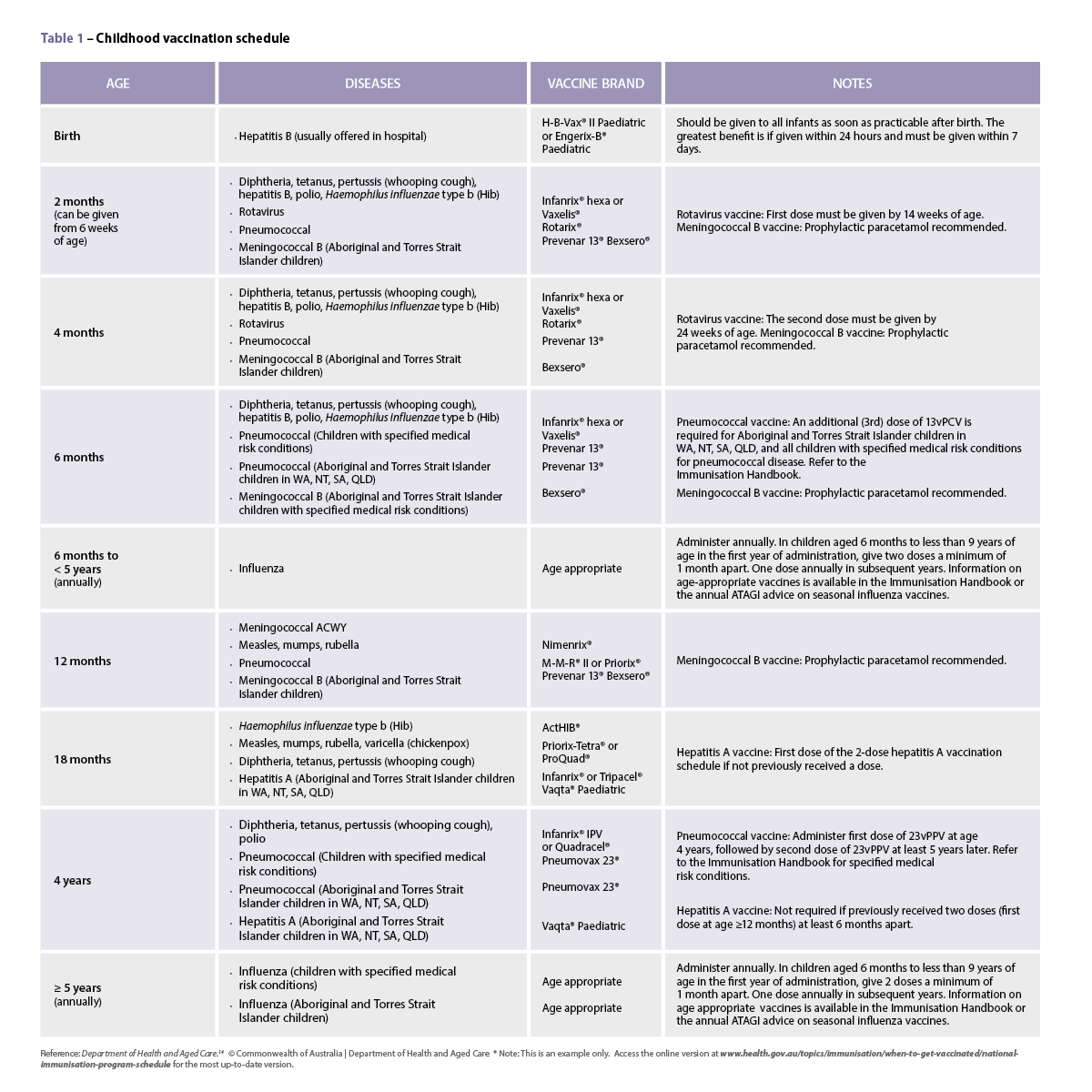

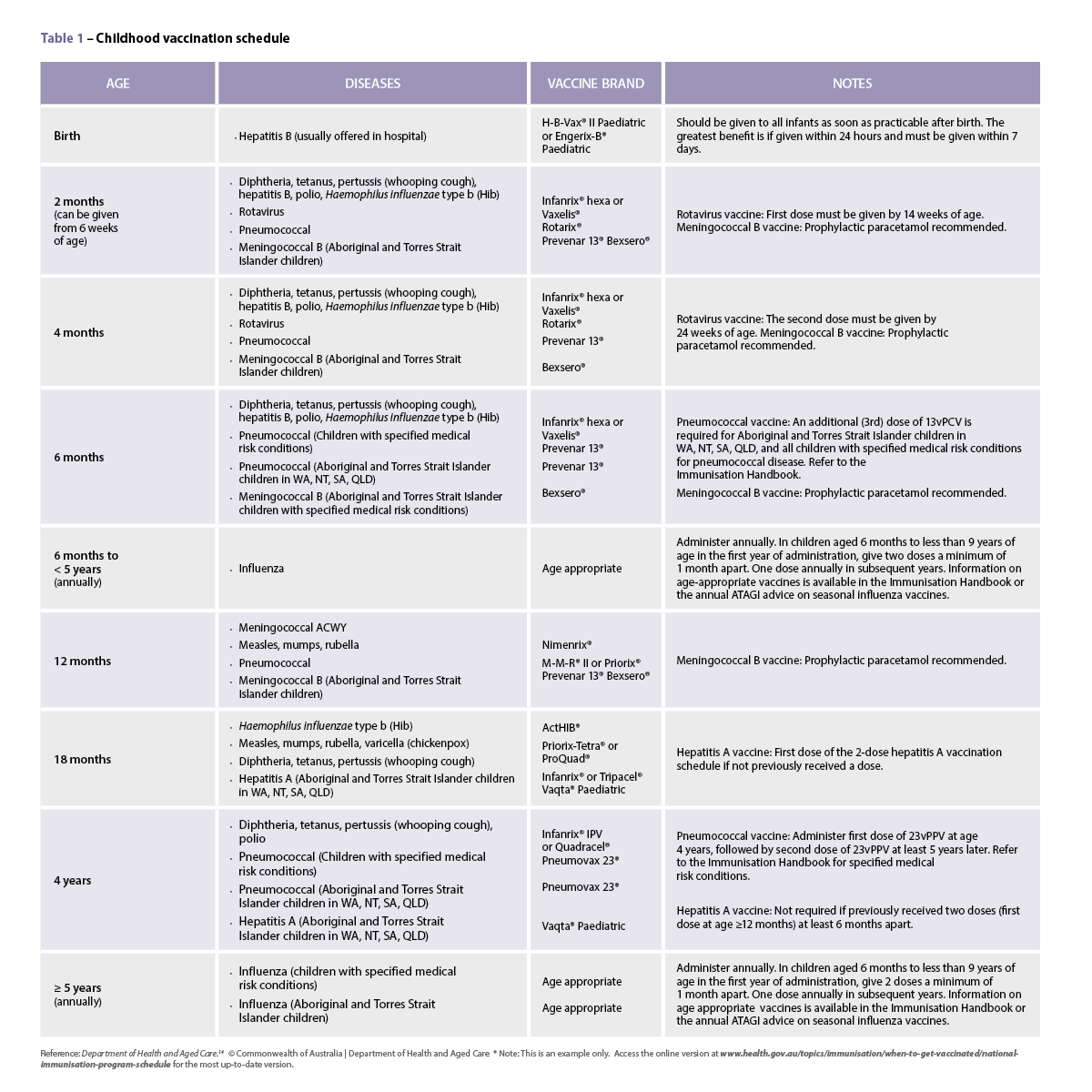

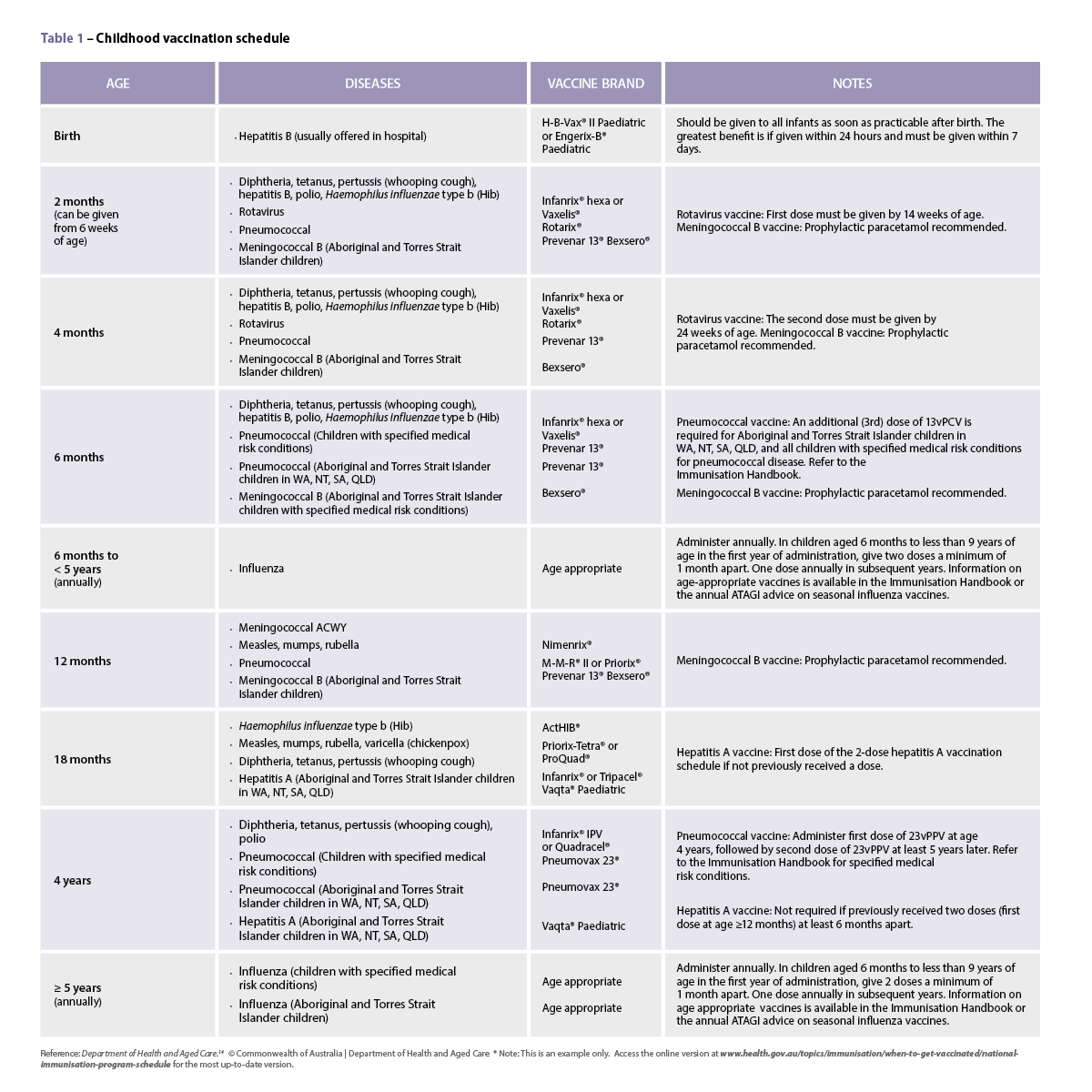

The Australian Immunisation Handbook provides clinical guidelines about using vaccines safely and effectively. It outlines the vaccines recommended for children and adults following an evidence-based approach.2 The National Immunisation Program schedule provides a guide to the recommended vaccines and their schedule (See Table 1).2

Case scenario

Case scenario

Edwin’s parents explain that he has kept up to date with all his vaccines so far and has no other health concerns. His 6-month vaccinations are being given in 3 days’ time. Looking at the vaccination schedule, you note that the upcoming vaccination will include diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP); hepatitis B; polio and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). All these vaccinations are now available in one combined product.3 You also note that for Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations, he likely received two injections as opposed to the one, with pneumococcal also required at that time.2

Reactions to vaccinations are common,2 and may include redness, swelling and soreness at the injection site, and sometimes a low-grade fever (38–38.5 °C).4 These reactions are usually mild and self-limiting.2

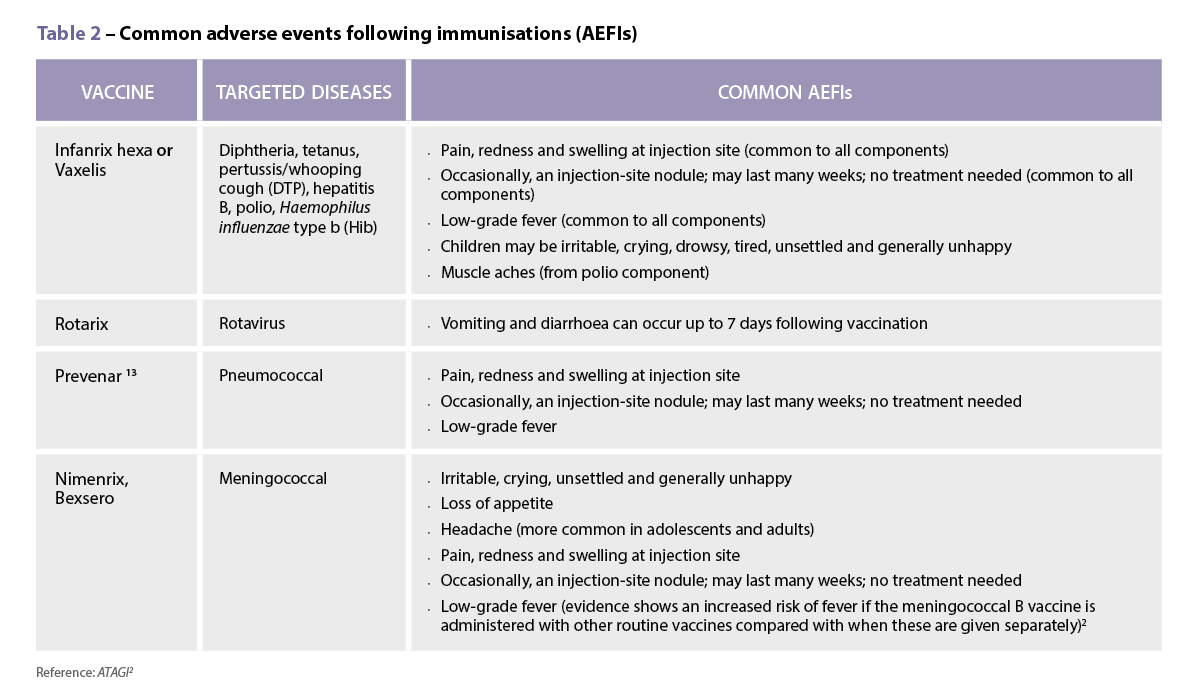

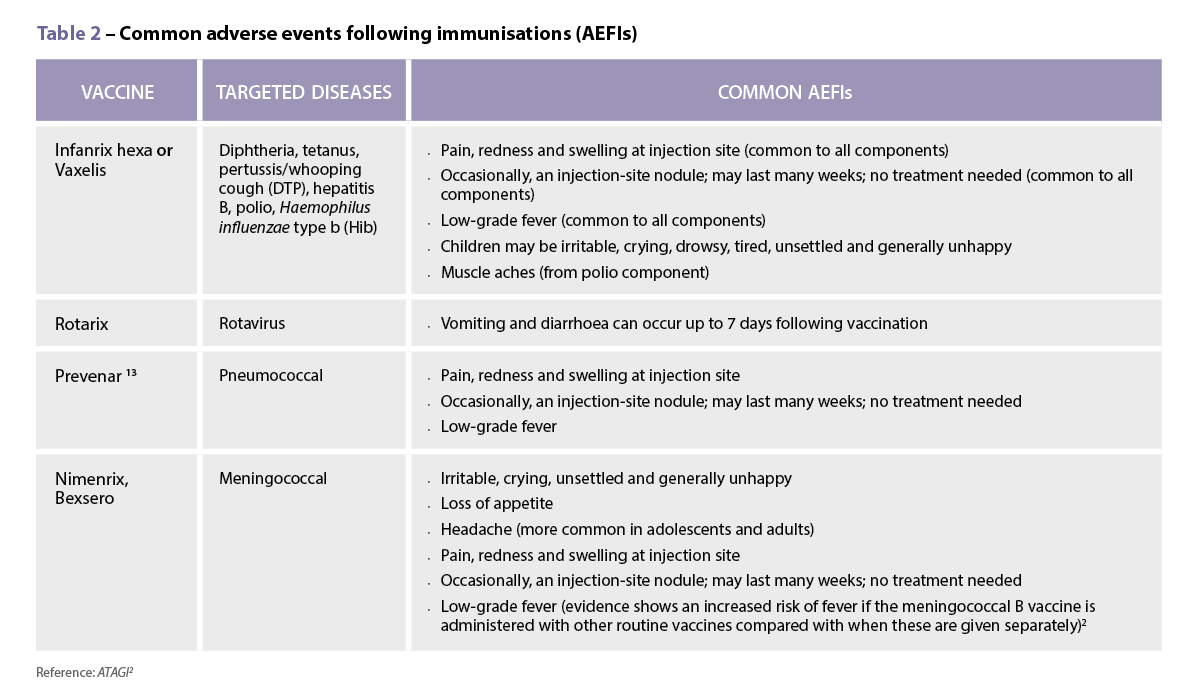

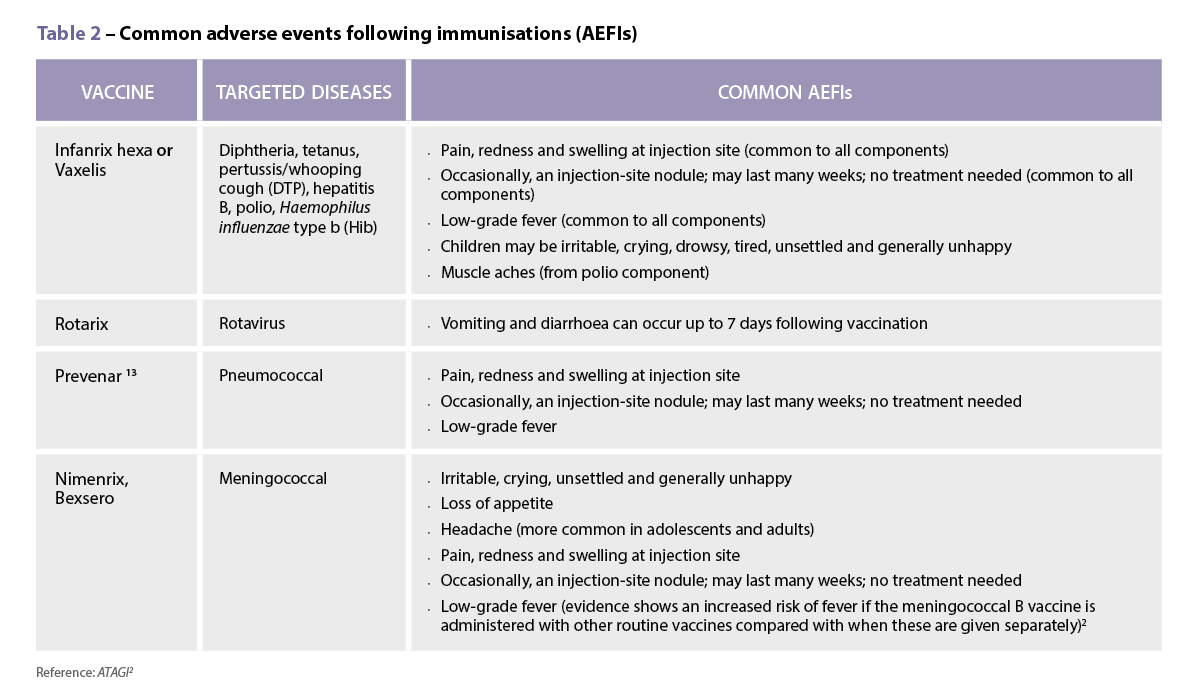

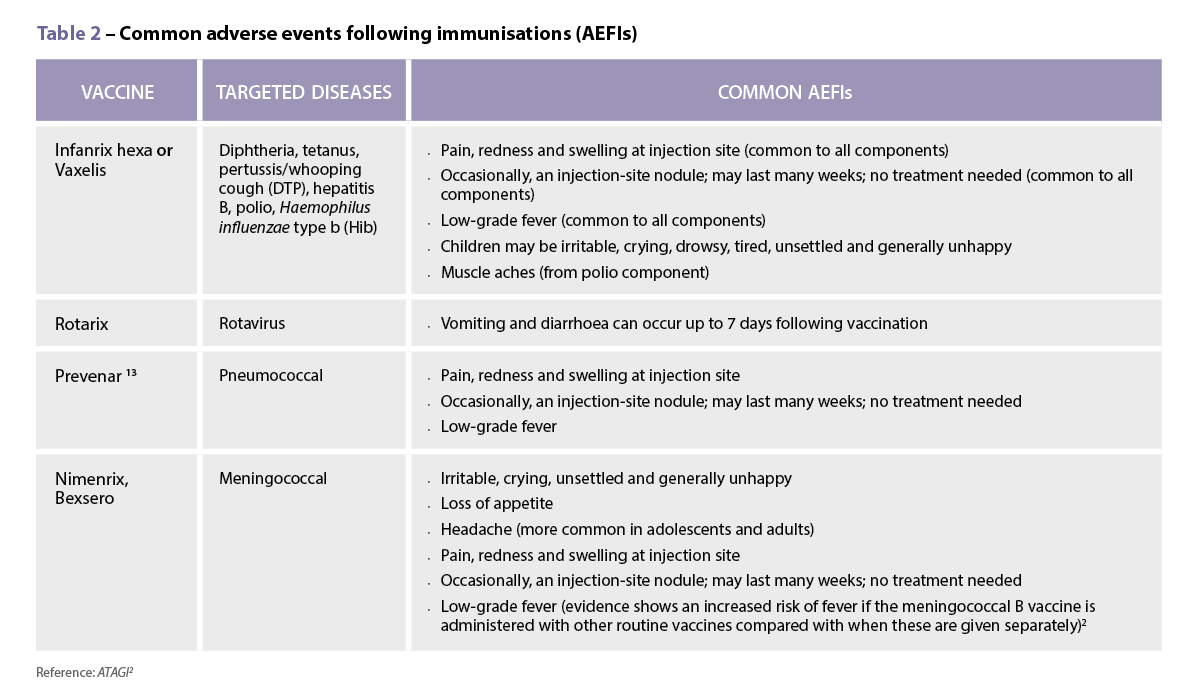

It is likely that Edwin’s low-grade fever and discomfort described by his parents after his 4-month injections were in line with the known common adverse effects associated with childhood vaccinations (see Table 2 ).2

According to the Australian Immunisation Handbook, it is not generally recommended to give a child prophylactic doses of paracetamol or ibuprofen prior to, or at the time of most vaccinations.2 In fact, there is some evidence that interfering with the body’s natural immune response may lower the effectiveness of vaccines.5 In a randomised controlled trial published in the Lancet, researchers demonstrated that antibody response was significantly reduced in the group of healthy infants that received prophylactic paracetamol at the time of both the primary and booster vaccinations for DPT, Haemophilus influenzae and pneumococcal.5

The study concluded that ‘although febrile reactions significantly decreased, prophylactic administration of antipyretic drugs at the time of vaccination should not be routinely recommended, since antibody responses to several vaccine antigens were reduced’.5

In contrast to this advice, however, the immunisation guidelines now recommend a dose of paracetamol 30 minutes prior to the administration of a meningococcal B vaccine.2 The vaccination schedule for healthy infants at low risk of disease recommends MenACWY vaccination at 12 months of age.2 For infants at higher risk of disease, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, they are recommended to also have the meningococcal B vaccine at 2, 4, 6 (with specified risk conditions) and 12 months also. These vaccines have been shown to be associated with the AEFIs listed in Table 2.2

Due to these adverse effects, the Australian Immunisation Handbook suggests that an appropriate 15 mg/kg/dose of paracetamol should be administered 30 minutes prior to – or as soon as possible after – meningococcal B vaccination and can be followed by two more doses of paracetamol given 6 hours apart, regardless of whether the child has a fever.2

The Australian Immunisation Handbook mentions several strategies to use following vaccination. Immediate aftercare includes strategies such as distracting the infant by immediately changing the infant’s position, such as picking them up and placing them over the parent or caregiver’s shoulder and asking the adult to move around.2

The administration of analgesics or antipyretics following vaccination is rarely required if a child is eating, drinking, playing and happy.13 However, the handbook has recently been updated to include the use of either paracetamol or ibuprofen if a fever of >38.5 oC occurs with associated pain symptoms, or if there is moderate pain at the injection site.2 This pain may be noticed if the infant is unsettled, and cries when the injection site is touched. These can be useful counselling points for parents or caregivers.

It is important to be aware of some of the common issues that arise with using these medicines.6 These include choosing the most appropriate agent to use; understanding the directions for use, including dose and dose-interval; and measuring the correct dose.6 There are also some common myths that parents and caregivers have surrounding the treatment of pain and fever in children that are discussed below.

Ibuprofen or paracetamol are considered first-line agents for pain with or without fever in children.7 For post-vaccination pain/fever in an infant 3 months and older, either agent would be appropriate.7,8

There are some instances where one agent may, however, be preferred over the other. For example, for a child whose pain may be more inflammatory in nature – such as teething, sprain or post-vaccination pain – an anti-inflammatory agent such as ibuprofen may be considered an appropriate choice.7,8

In an infant younger than 3 months of age, paracetamol would be the agent of choice, as ibuprofen is only recommended for use in children aged 3 months and older.

It is important to note that any infant younger than 3 months of age with fever should be referred to a general practitioner (GP).8

There are many caregivers who have been advised at certain times to administer both ibuprofen and paracetamol concurrently or to alternate doses.9,10 This practice is usually not recommended, particularly for mild pain or mild pain associated with fever. Given that many caregivers can struggle with accurately dosing even one medication, recommending using two agents at the same time is not advised,9,11 as complicating things with two agents could compound dose errors.

Two studies have looked at Australian and/or New Zealand caregivers’ skills in being able to determine an appropriate dose of liquid over-the-counter medicines for their child.9,11

Unfortunately, both of these studies highlighted serious flaws in caregivers’ abilities to recommend an appropriate weight-based dose of paracetamol or ibuprofen for their child. Paracetamol should be dosed at 15 mg/kg every 4–6 hours with a maximum of four doses in a 24-hour period.2 Ibuprofen is dosed at 5–10 mg/kg every 6–8 hours with a maximum of three doses in 24 hours recommended.2

One study found almost 1 in 2 caregivers selected an incorrect dose of a liquid medicine (either paracetamol or ibuprofen) in a ‘mock fever scenario’ involving their child, despite the original packaging being available for them to look at.11 More than 4% of the caregivers choosing paracetamol stated they would readminister the medication within 3 hours of the last dose, despite packaging indicating a 4–6-hour dose interval. Almost one-third of the caregivers who selected ibuprofen chose an incorrect dose interval of less than 6 hours.11

Poor knowledge surrounding the dose interval for children’s ibuprofen doses was also found in another study in which two-thirds of caregivers incorrectly believed ibuprofen could be administered up to 4 times a day, instead of the maximum of 3 doses in a 24-hour period when used for a non-prescription dose.10

In the first study, 1 in 6 (16%) caregivers measured a dose that was outside a 10% error margin of the intended dose they stated for their child.11 Another study found similar levels of liquid dosing accuracy, with 1 in 4 (24%) of doses deviating from what parents/caregivers had stated they would give.8 Of these deviations, 13% of doses deviated by more than 20% from the intended dose.9 This study also revealed that caregivers using medicine cups were more likely to measure an inaccurate dose in comparison to using a syringe.9 These findings further support that taking time to show parents/caregivers how to measure accurate doses and use accurate measuring devices is warranted.

Both parents and healthcare providers may have concerns about using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen due to a perceived risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects. However, research consistently shows that when used short term as directed, over-the-counter doses of ibuprofen have a similar tolerability profile in paediatric pain and fever.12,13 Both drugs are associated with a low risk of gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events in patients without contraindications or precautions.12,13

A common misconception is that ibuprofen must be taken with food to minimise GI adverse effects. However, the evidence suggests that for over-the-counter doses of ibuprofen, there is no need to take doses with food, as they are well-tolerated regardless of when the dose is given, and food may even slightly delay gastric absorption. This is true even for children’s dosing.12

Finally, many people believe that an appropriate way to manage fever in children is to place the child in a cold or tepid bath or sponge them in cold water.6 Unfortunately, this practice can in fact make children very uncomfortable and cause them to shiver, which in turn can drive temperatures higher.6 Rather, guidelines recommend dressing children in enough clothing, so they are not too hot or cold. If they are shivering, it is recommended to add another layer of clothing or a blanket until they stop. A face washer or sponge soaked in warm water may be used to also keep them comfortable.6

Routine childhood vaccinations can sometimes be associated with mild adverse effects. Understanding how non-pharmacological strategies and medicines are used to treat pain or fever episodes in this patient cohort is essential in the delivery of evidence-based care by pharmacists. Pharmacists can further support parents and caregivers by addressing misconceptions related to medicines administration around the time of vaccination.

Case scenario continuedYou explain to the Soe family that should Edwin develop a mild fever after vaccination, they should keep him hydrated and encourage rest.8 If the fever is making Edwin distressed, then medicine can be given.2 After your consultation with the Soe family, they decide not to dose Edwin prior to his 6-month vaccinations but stay alert for any distress following his shots. They have decided to purchase some ibuprofen this time and explain that, if they do end up using it, they will check his weight first and follow the directions, ensuring to wait at least 6 hours between doses if he needs more than one dose. |

Professor Rebekah Moles FPS, BPharm, DipHospPharm, PhD is a pharmacist and Professor at the Sydney Pharmacy School (University of Sydney).

Vaccine administration should be in accordance with relevant legislation, the Australian Immunisation Handbook, and state-based conditions specific to the vaccine.

[post_title] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [post_excerpt] => Routine childhood vaccinations can sometimes be associated with mild adverse effects. Understanding how non-pharmacological strategies and medicines are used to treat pain or fever episodes in this patient cohort is essential. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => pain-fever-childhood-vaccinations [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-04-15 10:18:15 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-15 00:18:15 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28888 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [title] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/pain-fever-childhood-vaccinations/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 29117 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29125

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-11 10:52:23

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-11 00:52:23

[post_content] => Maria Cooper MPS, PSA’s South Australian Early Career Pharmacist of the Year, is on a mission to improve the mental health and job satisfaction of young pharmacists.

What led you to pharmacy?

I’ve always loved science – and to talk! Growing up, my mum was a pharmaceutical scientist working in a laboratory. I wanted to work in the sciences just like her. One of the things that drew me to pharmacy was that every day could be different. I liked the potential to solve a different problem each day, and to see how your efforts made a positive impact on your community. It always brought me so much joy to hear that my advice directly allowed people to become happier, more confident and informed about their health.

Why focus on mental health in the pharmacy profession for your research?

In my undergraduate days, I remember being told that if going into research, you have to be passionate about the subject matter to succeed.

Working in community pharmacy full time during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic inspired me to apply for this PhD project. I had only been a registered pharmacist for about 5 years, but I was already feeling extremely burnt out, taken for granted and unappreciated in my role.

At the time, I was also working towards my Master of Clinical Pharmacy online through the University of Queensland, and despite it being hard work, it turned out to be a blessing in disguise. We were involved in a lot of group assignments with weekly Zoom study groups. Over time, the study sessions turned into an informal peer support space.

We shared how we were feeling and what we experienced at work that week. Then, we spent time building up and reassuring each other before we started to work on our project.

These conversations made me think about how important mental health was for pharmacists, and how many of us were silently struggling with burnout, especially during 2020 and 2021.

Tell us about the peer support program you developed.

Everyone in a peer support environment gains something through involvement, just by being in a space where they are not alone in their experiences.

There is a degree of separation between the participants; while everyone involved is an ECP, they don’t work at the same place, so they can talk about things going on at work that they might not feel comfortable sharing with colleagues.

I’ve seen the development of some tight-knit groups of pharmacists who might have never have met otherwise.

It’s been great to see how these connections have fostered a sense of support and camaraderie within the profession.

Engaging in a peer support program together will really benefit these pharmacists as their careers progress.

What did your research reveal about workplace stress among ECPs?

My research has shown that ECPs consistently experience moderate levels of stress, but these levels are higher in younger pharmacists and those who have registered more recently.

Overall, job satisfaction has remained ambivalent throughout the three cohort studies I have conducted. ECPs generally enjoy the nature of their work and relationships with colleagues, but have more dissatisfaction with workplace operations, including remuneration and contingent rewards. I’m working on a more in-depth interview project, hopefully to explore more about what facets of the pharmacy profession bring ECPs the most joy, as well as the most feelings of stress.

What ‘s your self-care advice for ECPs?

Remember: as a pharmacist, you cannot provide the best level of care when you are not cared for. Set boundaries. Don’t spend all your time at work. Go out with friends.

Keep up a regular hobby. Use annual leave to do things that bring you joy and relaxation. I still work part time as a community pharmacist, and love it more than ever. Taking time for my own rest and hobbies, when I work in the pharmacy now, I have more patience and kindness to impart to the people I’m helping. New graduates: you won’t know everything right away. But it’s okay! Ask for help.

[post_title] => Mental health missionary

[post_excerpt] => Maria Cooper MPS, PSA’s South Australian Early Career Pharmacist of the Year, is on a mission to improve young pharmacists' mental health.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => mental-health-missionary

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-04-14 18:14:15

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-14 08:14:15

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29125

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Mental health missionary

[title] => Mental health missionary

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/mental-health-missionary/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 29130

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29172

[post_author] => 250

[post_date] => 2025-04-16 15:41:17

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-16 05:41:17

[post_content] => The Fair Work Commission’s Expert Panel for pay equity in the care and community sector has today issued its initial decision on the Gender-based undervaluation – priority awards review – making determinations on the Pharmacy Industry Award 2020, which most community pharmacists are employed under.

What did the Expert Panel find?

The Expert Panel found that pharmacists covered by the Pharmacy Industry Award 2020 (and several other awards) have been the subject of gender-based undervaluation.

As a result, the Expert Panel has determined that findings constitute work value reasons, justifying variation of the modern award minimum wage rates across all categories of pharmacists.

What is ‘gender-based undervaluation’?

Gender-based undervaluation considers a range of factors to determine whether minimum award pay rates are undervalued because of assumptions based on gender.

The range of factors considered extends to historical undervaluing, exercise of ‘invisible skills’, exercise of caring work and workforce qualifications, among others.

How does the Expert Panel intend to address the undervaluation?

For pharmacists employed by the Pharmacy Industry Award 2020, the Expert Panel has issued a determination that there will be a total increase in the minimum wage rates of 14.1% over three years.

This increase will be implemented in three equal phases on:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28725

[post_author] => 10075

[post_date] => 2025-04-16 10:13:21

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-16 00:13:21

[post_content] => Case scenario

Malcolm (68 years old, male) visits your pharmacy with a new prescription for sacubitril/valsartan. He mentions he has recently been diagnosed with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). You review his records and confirm he is still taking metformin/sitagliptin for type 2 diabetes. Malcolm explains that he has taken this for many years, and that his general practitioner has advised him that his blood glucose control needs to be better. He expresses frustration that the shortness of breath from his heart failure limits his ability to exercise and improve his diabetes. Malcolm hopes that starting this new medicine will improve this.

After reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Already read the CPD in the journal? Scroll to the bottom to SUBMIT ANSWERS.

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome caused by the inability of the heart muscle to provide adequate cardiac output and/or the presence of increased cardiac pressure. This is due to either a structural or functional abnormality of the heart.1 The clinical syndrome consists of symptoms such as breathlessness and fatigue and may be accompanied by signs of fluid accumulation such as peripheral oedema, elevated jugular venous pressure and pulmonary crackles.1

In many cases, heart failure may be both preventable and treatable. Choice of treatment depends on the type of heart failure present, with management being primarily pharmacological.1

Pharmacists play an essential role in optimising pharmacotherapy for heart failure patients, providing recommendations on safe and effective dose titration and appropriate pharmacological management, as well as providing education, counselling and support for adherence.2

Heart failure remains a global public health issue that affects at least 38 million people worldwide.2 It is a major cause of hospitalisation in Australia and is associated with significant healthcare costs.3

Heart failure has a poor prognosis and results in markedly reduced quality of life.1 Readmission to hospital is extremely common, with about 1 in 3 patients being readmitted in the first month, and up to 15% of patients dying within the first 6 months, after being discharged from hospital.4 By 12 months post-discharge, approximately 25% of heart failure patients will have died.5

Concerningly, due to population aging and increasing prevalence of comorbidities, heart failure hospitalisations could increase by as much as 50% in the next 25 years.1

Categorisation of heart failure

Categorisation of heart failureHeart failure is categorised according to the measurement of the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Knowing the LVEF at time of diagnosis is crucial, as this guides treatment.1 Heart failure is categorised as either1,6,7:

HFrEF

For HFrEF, there are effective pharmacological therapies, supported by robust, high-quality evidence. These include what has now become known as ‘the four pillars’, and these collectively make up guideline-directed medical therapy for HFrEF. These include9–11:

All patients with HFrEF should be prescribed all four agents (unless contraindicated or not tolerated), with early initiation being associated with the best outcomes.1,9,10 Other therapies are available as HFrEF progresses, however the ‘four pillars’ are the cornerstone of HFrEF treatment.10

HFmrEF

There is limited evidence to support specific recommendations for the pharmacological management of HFmrEF.1 Some studies suggest that patients with HFmrEF may receive similar benefit from a beta blocker, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and a renin angiotensin system inhibitor as in HFrEF, and SGLT2is have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalisation for heart failure.14 The medicines used to treat HFrEF are often used to treat HFmrEF, however the confidence in prognostic benefits is much less.1,14

HFpEF

For the treatment of HFpEF, no medicines have demonstrated a statistically significant benefit on mortality.1 Recommended treatment consists of15:

The use of an SGLT2i in HFpEF has not been shown to improve mortality to the same extent as for HFrEF. However, an SGLT2i is still recommended because major trials have shown they can still offer some benefits.16,17

The EMPEROR-Preserved trial demonstrated a 21% lower relative risk in the composite of cardiovascular death or hospitalisation for heart failure with the use of empagliflozin in the treatment of HFpEF compared with placebo – a result driven primarily by a reduction in risk of hospitalisation rather than mortality.16 Importantly, this benefit was seen regardless of the diabetic status of the patient.16 This benefit was later reinforced by the DELIVER trial which showed a lower risk of its composite primary outcome of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death with dapagliflozin use, compared to placebo for those with HFmrEF and HFpEF.18 As a result, SGLT2is have received a strong recommendation for the management of HFpEF in treatment guidelines.1

Additionally, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists are used in clinical practice because they have been associated with a reduction in risk of hospitalisation for HFpEF patients, as demonstrated by the TOPCAT trial.19

A focus on SGLT2is

A focus on SGLT2isInitially developed as a medicine used for type 2 diabetes, SGLT2is have become a crucial cardiovascular drug class, as demonstrated above by their role in the management of heart failure, and now have renal and cardiovascular indications irrespective of type 2 diabetic status. This is largely due to results of cardiovascular outcome trials mandated by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008. These trials led to findings that have significantly changed clinical practice.20 They arose from concerns of cardiovascular risks with certain medicines used for type 2 diabetes, evidence suggesting rosiglitazone may increase the risk of myocardial infarction, and in recognition of the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease in these patients.20

SGLT2is lower blood glucose by inhibiting SGLT2 transporters in the proximal tubules of the kidneys to decrease glucose reabsorption, which increases the excretion of glucose in the urine.21 Sodium excretion also occurs because the SGLT2 receptor is close to, and works together with, a sodium/hydrogen exchanger, which is a major receptor responsible for sodium reuptake.22

Although SGLT2is lower blood glucose, blood pressure and contribute to diuresis, their benefits in terms of renal and cardiovascular outcomes cannot be solely attributed to these properties, as similar clinical benefits are not seen with other agents that lower glucose, blood pressure or increase natriuresis to similar or greater extent.23,24 The mechanism of action linked to these benefits is complex, and appears to also be a combination of anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects, a reduction in epicardial fat and a reduction in hyperinsulinaemia.21

Additional evidence also suggests a reduction in oxidative stress, less coronary microvascular injury and improved contractile performance.23 Emerging clinical evidence may also suggest antiarrhythmic properties, which is particularly important given that ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death is a major cause of death in heart failure patients.21 Some trials have demonstrated a decrease in sudden cardiac death for patients using a SGLT2i.21

The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial in 2015 was a landmark study, demonstrating that empagliflozin significantly reduced cardiovascular death among high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes, compared to placebo.25 Importantly, it also suggested renal benefits, with less cases of acute renal failure in the empagliflozin group.25 These findings were later confirmed by the EMPA-Kidney (empagliflozin) and DAPA-CKD (dapagliflozin) trials, which both showed reduced rates of death due to renal disease, slower decline in renal function and delayed time to needing dialysis.26–28

The cardiovascular benefits of these medicines went on to be confirmed in further trials including the DAPA-HF (2019), EMPEROR Reduced (2020), EMPEROR Preserved (2021) and DELIVER (2022) trials.16,18,29,30

Key practice points

Knowledge to practice

Knowledge to practice The use of heart failure guideline-directed medical therapy in HFrEF can have a significant impact on patient outcomes. The combination of the ‘four pillars’ (a heart failure beta blocker, an mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, a renin angiotensin system inhibitor and an SGLT2i) has the ability to improve life expectancy, delay disease progression, decrease heart failure symptoms and improve quality of life.9,10 All patients with HFrEF should be prescribed all four agents unless a contraindication or intolerance exists preventing their use.32

In HFpEF, there are currently no medicines that demonstrate a statistically significant benefit on mortality. However, the use of SGLT2is has been shown to reduce risk of hospitalisation (regardless of diabetic status) and are recommended to be used by guidelines as part of its management, and in the managment of HFmrEF.1,9,14

Heart failure remains a significant health burden, but modern medicines, particularly SGLT2is, can offer significant benefits. Pharmacists play a pivotal role in optimising therapy, ensuring adherence, and providing education to patients. By leveraging their expertise as medication experts, pharmacists can profoundly impact outcomes, improving survival and quality of life for individuals living with heart failure and associated comorbidities.

Case scenario continuedRecognising the benefits of an SGLT2i for both Malcolm’s heart failure and diabetes, you discuss the option of adding an SGLT2i to his regimen, and the potential benefits and risks. Malcolm explains that his main priority is to get his heart failure symptoms under control so that he can play with his grandchildren and exercise comfortably. At Malcolm’s request, you contact his GP, and it is agreed to commence empagliflozin 10 mg daily (after ensuring his eGFR is appropriate). This intervention may help to reduce Malcolm’s risk of death from heart failure, improve his quality of life, delay disease progression, improve diabetic control and assist in helping him achieve his health goals. |

[cpd_submit_answer_button]

Cassie Potts (she/her) BPharm, GradCertChronCondMgt, FANZCAP (Cardiol), AdPhaM is a Senior Clinical Pharmacist with SA Pharmacy and has over 11 years of experience specialising in heart failure as part of the cardiology team at Flinders Medical Centre. She serves on the AdPha Cardiology Leadership Committee and currently practises within the intensive care unit at the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

Hana Numan (she/her) BPharm (NZ), PGDipClinPharm (NZ), MPS (NZ)

[post_title] => SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure [post_excerpt] => Heart failure remains a significant health burden, but modern medicines, particularly SGLT2is, can offer significant benefits. Pharmacists play a pivotal role in optimising therapy, ensuring adherence, and providing education to patients. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => sglt2-inhibitors-in-heart-failure [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-04-16 15:42:24 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-16 05:42:24 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28725 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure [title] => SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/sglt2-inhibitors-in-heart-failure/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 29161 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29133

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-14 16:21:01

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-14 06:21:01

[post_content] => Data shows that while community pharmacists have smashed previous early-season influenza vaccination records, national coverage still lags dangerously.

Australia is experiencing its worst start to an influenza season, with case numbers surging and vaccination rates falling behind across key age groups.

Amid early peaks, a rise in influenza B cases, and sluggish immunisation uptake, Australian Pharmacist presents a visual snapshot of how the 2025 flu season is unfolding – and what must be done now to prevent a looming public health crisis.

1. Influenza case numbers have reached unprecedented levels to start 2025

This year, influenza cases have reached their highest level in almost a quarter of a century (24 years). To date, there have been 58,203 notifications of laboratory-confirmed influenza reported to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) – with 2025 Quarter One case reports dwarfing that of previous years.

The flu season started earlier than usual this year, with cases surging sooner than in previous years. Early peaks often lead to higher overall case numbers – particularly when coupled with low immunisation rates.

In 2025, there has been a higher proportion of influenza B cases than in previous years, particularly in school-aged children and young adults, said Professor Anthony Lawler, Australian Government Chief Medical Officer. ‘Influenza B is often more common in children, and can result in more severe infections in children,’ he said.

[caption id="attachment_29144" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Professor Anthony Lawler, Australian Government Chief Medical Officer, got his 2025 vaccine at a Canberra community pharmacy[/caption]

With the northern hemisphere experiencing a severe influenza season, and strains in this region typically migrating south, Rural Doctors Association of Victoria president Louise Manning said the trend was ‘worrying’.

‘We're quite concerned that, given the severity of symptoms and the number of hospitalisations in the northern hemisphere in their winter, that we'll have a similar picture here,’ Dr Manning told the ABC.

Professor Anthony Lawler, Australian Government Chief Medical Officer, got his 2025 vaccine at a Canberra community pharmacy[/caption]

With the northern hemisphere experiencing a severe influenza season, and strains in this region typically migrating south, Rural Doctors Association of Victoria president Louise Manning said the trend was ‘worrying’.

‘We're quite concerned that, given the severity of symptoms and the number of hospitalisations in the northern hemisphere in their winter, that we'll have a similar picture here,’ Dr Manning told the ABC.

2. Pharmacists have had a fast start to influenza vaccination

Data over the last 4 years shows pharmacist-administered vaccines are experiencing continued growth.

Key factors influencing this growth include increased trust in the pharmacy profession to administer vaccines as well as accessibility. With longer operating hours – including evenings and weekends – pharmacies offer greater accessibility, allowing patients to receive influenza vaccinations without appointments or extended wait times. This convenience factor makes pharmacy a more flexible alternative to traditional healthcare settings such as General Practice.

3. Vaccination rates are far too low in children under 5

When it comes to influenza, children aged 0–5 are one of the most vulnerable cohorts – with the high risk of severe complications sometimes leading to hospitalisations, often due to pneumonia, and death.

Despite the risks, vaccination rates remain low in this age cohort, with only 7,398 children aged 0–5 receiving the influenza vaccine so far this year.

Despite the influenza vaccine being covered under the National Immunisation Program for this age group, less than half (45%) of parents are aware that their child can be vaccinated free of charge.

In 2024, only 25.8% of children 6 months to 4 years received an influenza vaccine – with three quarters of this at risk population remaining unvaccinated.

Many parents believe that influenza is not a serious disease or that the vaccine is ineffective or unsafe, with 29% exposed to misinformation and 26% influenced by anti-vaccine sentiment through social media.

Vaccine access can also prove challenging. To boost participation in young children, PSA maintains that there should be ‘no wrong door’ when it comes to vaccination – meaning pharmacists should be able to provide influenza vaccines alongside other childhood immunisations, said Chris Campbell MPS, PSA General Manager Policy and Program Delivery.

‘What [this] does do is increase the convenience for someone to be able to get the vaccine at a time and place of their choosing,’ he said.

‘There should be an increase in vaccine uptake in children under 5 years of age when there’s an opportunity for an entire family to come to the pharmacy and get vaccinated.’

4. Vaccination rates in all cohorts need to improve to stave off a devastating influenza season

The latest data on influenza vaccination coverage in Australia for 2025 reveals concerningly low uptake across all age groups and jurisdictions. Western Australia, Tasmania, and Victoria report particularly low figures at this stage among children 6 months to >5 years and aged 5 to under 15 years, with some states showing uptake as low as 0.1%.

Among patients aged 50 to under 65 years, national coverage sits at 2.8%, with Queensland (4.5%) and South Australia (4.0%) leading the charge. Coverage increases more significantly in the over 65s demographic – with South Australia (14.2%) and Queensland (12.6%) again topping vaccination coverage.

Vaccine manufacturers are also expecting a surge in cases, with CSLSeqirus revealing it has boosted its vaccine output by 100,000 doses this season.

To protect the community from a particularly nasty influenza season, experts have urged people to roll up their sleeves and get vaccinated.

‘If you don't want to get crook get vaccinated,’ Public Health Association of Australia chief executive Terry Slevin said.

‘You're less likely to get crook and if you do get crook, you'll be crook for a shorter period of time ... and reduce the misery.’

[post_title] => Flu cases surge to record highs as vaccination rates stall

[post_excerpt] => While community pharmacists have smashed previous early-season influenza vaccination records, national coverage still lags dangerously.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => flu-cases-surge-to-record-highs-as-vaccination-rates-stall

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

https://www.immunisationcoalition.org.au/australia-sees-record-breaking-influenza-season-amid-declining-vaccination-rates/

[post_modified] => 2025-04-14 18:14:43

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-14 08:14:43

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=29133

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Flu cases surge to record highs as vaccination rates stall

[title] => Flu cases surge to record highs as vaccination rates stall

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/flu-cases-surge-to-record-highs-as-vaccination-rates-stall/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 29148

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28888

[post_author] => 10042

[post_date] => 2025-04-11 12:00:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-11 02:00:11

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_28205" align="alignright" width="182"] This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

Mr and Mrs Soe come into your pharmacy pushing young Edwin in his pram. Edwin is due for his 6-month vaccinations and has an appointment at his GP coming up this week. The Soe family want to get ‘the best pain and fever medicine they can, because after Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations he was quite upset and had a little bit of a fever afterwards (38.1 ºC)’.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Active immunisation uses vaccines to stimulate the immune system.1 In turn, after the administration of vaccines that contain one or more immunogens, the immune system can react to a toxin or pathogen more effectively, helping prevent or reduce the severity of disease.1 Vaccines may induce antibody production by B lymphocytes, that can bind specifically to a toxin or pathogen.1 They may also boost numbers of killer cells such as CD8+ T cells to kill infected cells, or they may increase CD4+ T cells to help more efficiently ‘clear out’ infected cells.1

Regardless of each vaccine’s mechanism of action, immunity after active immunisation generally lasts for months to many years.2 How long the immune response lasts depends on the nature of the vaccine, the type of immune response (antibody or T-cell) and host factors.1 Because of this, inducing the desired immune response may require a series of vaccine doses.2

The Australian Immunisation Handbook provides clinical guidelines about using vaccines safely and effectively. It outlines the vaccines recommended for children and adults following an evidence-based approach.2 The National Immunisation Program schedule provides a guide to the recommended vaccines and their schedule (See Table 1).2

Case scenario

Case scenario

Edwin’s parents explain that he has kept up to date with all his vaccines so far and has no other health concerns. His 6-month vaccinations are being given in 3 days’ time. Looking at the vaccination schedule, you note that the upcoming vaccination will include diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (DTP); hepatitis B; polio and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). All these vaccinations are now available in one combined product.3 You also note that for Edwin’s 4-month vaccinations, he likely received two injections as opposed to the one, with pneumococcal also required at that time.2

Reactions to vaccinations are common,2 and may include redness, swelling and soreness at the injection site, and sometimes a low-grade fever (38–38.5 °C).4 These reactions are usually mild and self-limiting.2

It is likely that Edwin’s low-grade fever and discomfort described by his parents after his 4-month injections were in line with the known common adverse effects associated with childhood vaccinations (see Table 2 ).2

According to the Australian Immunisation Handbook, it is not generally recommended to give a child prophylactic doses of paracetamol or ibuprofen prior to, or at the time of most vaccinations.2 In fact, there is some evidence that interfering with the body’s natural immune response may lower the effectiveness of vaccines.5 In a randomised controlled trial published in the Lancet, researchers demonstrated that antibody response was significantly reduced in the group of healthy infants that received prophylactic paracetamol at the time of both the primary and booster vaccinations for DPT, Haemophilus influenzae and pneumococcal.5

The study concluded that ‘although febrile reactions significantly decreased, prophylactic administration of antipyretic drugs at the time of vaccination should not be routinely recommended, since antibody responses to several vaccine antigens were reduced’.5

In contrast to this advice, however, the immunisation guidelines now recommend a dose of paracetamol 30 minutes prior to the administration of a meningococcal B vaccine.2 The vaccination schedule for healthy infants at low risk of disease recommends MenACWY vaccination at 12 months of age.2 For infants at higher risk of disease, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, they are recommended to also have the meningococcal B vaccine at 2, 4, 6 (with specified risk conditions) and 12 months also. These vaccines have been shown to be associated with the AEFIs listed in Table 2.2

Due to these adverse effects, the Australian Immunisation Handbook suggests that an appropriate 15 mg/kg/dose of paracetamol should be administered 30 minutes prior to – or as soon as possible after – meningococcal B vaccination and can be followed by two more doses of paracetamol given 6 hours apart, regardless of whether the child has a fever.2

The Australian Immunisation Handbook mentions several strategies to use following vaccination. Immediate aftercare includes strategies such as distracting the infant by immediately changing the infant’s position, such as picking them up and placing them over the parent or caregiver’s shoulder and asking the adult to move around.2

The administration of analgesics or antipyretics following vaccination is rarely required if a child is eating, drinking, playing and happy.13 However, the handbook has recently been updated to include the use of either paracetamol or ibuprofen if a fever of >38.5 oC occurs with associated pain symptoms, or if there is moderate pain at the injection site.2 This pain may be noticed if the infant is unsettled, and cries when the injection site is touched. These can be useful counselling points for parents or caregivers.

It is important to be aware of some of the common issues that arise with using these medicines.6 These include choosing the most appropriate agent to use; understanding the directions for use, including dose and dose-interval; and measuring the correct dose.6 There are also some common myths that parents and caregivers have surrounding the treatment of pain and fever in children that are discussed below.

Ibuprofen or paracetamol are considered first-line agents for pain with or without fever in children.7 For post-vaccination pain/fever in an infant 3 months and older, either agent would be appropriate.7,8

There are some instances where one agent may, however, be preferred over the other. For example, for a child whose pain may be more inflammatory in nature – such as teething, sprain or post-vaccination pain – an anti-inflammatory agent such as ibuprofen may be considered an appropriate choice.7,8

In an infant younger than 3 months of age, paracetamol would be the agent of choice, as ibuprofen is only recommended for use in children aged 3 months and older.

It is important to note that any infant younger than 3 months of age with fever should be referred to a general practitioner (GP).8

There are many caregivers who have been advised at certain times to administer both ibuprofen and paracetamol concurrently or to alternate doses.9,10 This practice is usually not recommended, particularly for mild pain or mild pain associated with fever. Given that many caregivers can struggle with accurately dosing even one medication, recommending using two agents at the same time is not advised,9,11 as complicating things with two agents could compound dose errors.

Two studies have looked at Australian and/or New Zealand caregivers’ skills in being able to determine an appropriate dose of liquid over-the-counter medicines for their child.9,11

Unfortunately, both of these studies highlighted serious flaws in caregivers’ abilities to recommend an appropriate weight-based dose of paracetamol or ibuprofen for their child. Paracetamol should be dosed at 15 mg/kg every 4–6 hours with a maximum of four doses in a 24-hour period.2 Ibuprofen is dosed at 5–10 mg/kg every 6–8 hours with a maximum of three doses in 24 hours recommended.2

One study found almost 1 in 2 caregivers selected an incorrect dose of a liquid medicine (either paracetamol or ibuprofen) in a ‘mock fever scenario’ involving their child, despite the original packaging being available for them to look at.11 More than 4% of the caregivers choosing paracetamol stated they would readminister the medication within 3 hours of the last dose, despite packaging indicating a 4–6-hour dose interval. Almost one-third of the caregivers who selected ibuprofen chose an incorrect dose interval of less than 6 hours.11

Poor knowledge surrounding the dose interval for children’s ibuprofen doses was also found in another study in which two-thirds of caregivers incorrectly believed ibuprofen could be administered up to 4 times a day, instead of the maximum of 3 doses in a 24-hour period when used for a non-prescription dose.10

In the first study, 1 in 6 (16%) caregivers measured a dose that was outside a 10% error margin of the intended dose they stated for their child.11 Another study found similar levels of liquid dosing accuracy, with 1 in 4 (24%) of doses deviating from what parents/caregivers had stated they would give.8 Of these deviations, 13% of doses deviated by more than 20% from the intended dose.9 This study also revealed that caregivers using medicine cups were more likely to measure an inaccurate dose in comparison to using a syringe.9 These findings further support that taking time to show parents/caregivers how to measure accurate doses and use accurate measuring devices is warranted.

Both parents and healthcare providers may have concerns about using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen due to a perceived risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects. However, research consistently shows that when used short term as directed, over-the-counter doses of ibuprofen have a similar tolerability profile in paediatric pain and fever.12,13 Both drugs are associated with a low risk of gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events in patients without contraindications or precautions.12,13

A common misconception is that ibuprofen must be taken with food to minimise GI adverse effects. However, the evidence suggests that for over-the-counter doses of ibuprofen, there is no need to take doses with food, as they are well-tolerated regardless of when the dose is given, and food may even slightly delay gastric absorption. This is true even for children’s dosing.12

Finally, many people believe that an appropriate way to manage fever in children is to place the child in a cold or tepid bath or sponge them in cold water.6 Unfortunately, this practice can in fact make children very uncomfortable and cause them to shiver, which in turn can drive temperatures higher.6 Rather, guidelines recommend dressing children in enough clothing, so they are not too hot or cold. If they are shivering, it is recommended to add another layer of clothing or a blanket until they stop. A face washer or sponge soaked in warm water may be used to also keep them comfortable.6

Routine childhood vaccinations can sometimes be associated with mild adverse effects. Understanding how non-pharmacological strategies and medicines are used to treat pain or fever episodes in this patient cohort is essential in the delivery of evidence-based care by pharmacists. Pharmacists can further support parents and caregivers by addressing misconceptions related to medicines administration around the time of vaccination.

Case scenario continuedYou explain to the Soe family that should Edwin develop a mild fever after vaccination, they should keep him hydrated and encourage rest.8 If the fever is making Edwin distressed, then medicine can be given.2 After your consultation with the Soe family, they decide not to dose Edwin prior to his 6-month vaccinations but stay alert for any distress following his shots. They have decided to purchase some ibuprofen this time and explain that, if they do end up using it, they will check his weight first and follow the directions, ensuring to wait at least 6 hours between doses if he needs more than one dose. |

Professor Rebekah Moles FPS, BPharm, DipHospPharm, PhD is a pharmacist and Professor at the Sydney Pharmacy School (University of Sydney).

Vaccine administration should be in accordance with relevant legislation, the Australian Immunisation Handbook, and state-based conditions specific to the vaccine.

[post_title] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [post_excerpt] => Routine childhood vaccinations can sometimes be associated with mild adverse effects. Understanding how non-pharmacological strategies and medicines are used to treat pain or fever episodes in this patient cohort is essential. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => pain-fever-childhood-vaccinations [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-04-15 10:18:15 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-04-15 00:18:15 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28888 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [title] => Managing pain and fever associated with childhood vaccination [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/pain-fever-childhood-vaccinations/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 29117 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 29125

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-04-11 10:52:23

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-04-11 00:52:23

[post_content] => Maria Cooper MPS, PSA’s South Australian Early Career Pharmacist of the Year, is on a mission to improve the mental health and job satisfaction of young pharmacists.

What led you to pharmacy?

I’ve always loved science – and to talk! Growing up, my mum was a pharmaceutical scientist working in a laboratory. I wanted to work in the sciences just like her. One of the things that drew me to pharmacy was that every day could be different. I liked the potential to solve a different problem each day, and to see how your efforts made a positive impact on your community. It always brought me so much joy to hear that my advice directly allowed people to become happier, more confident and informed about their health.

Why focus on mental health in the pharmacy profession for your research?

In my undergraduate days, I remember being told that if going into research, you have to be passionate about the subject matter to succeed.

Working in community pharmacy full time during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic inspired me to apply for this PhD project. I had only been a registered pharmacist for about 5 years, but I was already feeling extremely burnt out, taken for granted and unappreciated in my role.

At the time, I was also working towards my Master of Clinical Pharmacy online through the University of Queensland, and despite it being hard work, it turned out to be a blessing in disguise. We were involved in a lot of group assignments with weekly Zoom study groups. Over time, the study sessions turned into an informal peer support space.

We shared how we were feeling and what we experienced at work that week. Then, we spent time building up and reassuring each other before we started to work on our project.

These conversations made me think about how important mental health was for pharmacists, and how many of us were silently struggling with burnout, especially during 2020 and 2021.

Tell us about the peer support program you developed.