Pharmacists in Australia are now predominantly young and female, with 5–10 years’ experience and moving into leadership roles at a rate not previously seen in the profession.

In just 4 years Kate Fulford MPS has sampled the diversity of pharmacy – working in hospitals, aged care, general practice and research – often combining several roles concurrently.

She’s also developed educational programs for health professionals to help improve the understanding of dementia care as well as overseen the development of an app to reduce unnecessary use of antipsychotic medicines for people with dementia. For challenging the scope of pharmacy practice through such innovation she was named PSA’s WA Early Career Pharmacist of the Year in May.

‘If you are willing to put in the work there are infinite opportunities for pharmacists in every area of healthcare,’ she says. ‘You have to be willing to take the risks and step outside your comfort zone.’

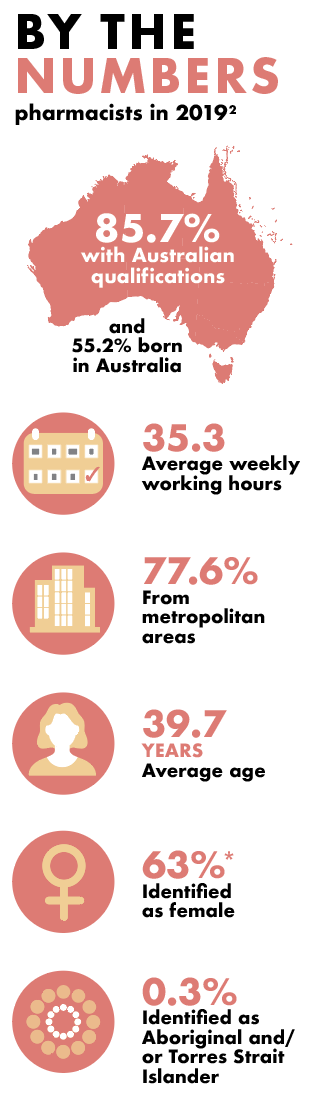

Ms Fulford, 30, is part of the changing demographic of Australian pharmacy. Pharmacists aged under 35 account for more than 40% of the workforce, and almost two-thirds of those registered in Australia are female. In 1992 there were 12,525 employed pharmacists compared to nearly 31,000 three decades later.1

These early career pharmacists (ECPs) are changing the practice profile in Australia. In fact, they are ‘redefining’ the modern pharmacist’, according to PSA National President Associate Professor Chris Freeman.

‘The number of Early Career Pharmacists who are 5–10 years into their career now represent the majority of ECPs across Australia. Collectively, this base represents a wealth of knowledge, skills and experience, all of which enrich the profession,’ he says.

Young pharmacists like Ms Fulford are forging new career paths in multidisciplinary healthcare teams in aged care, general practice, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) and research, complementing the established pathways in community and hospital pharmacy.

New faces on recently elected state branch committees are ECPs, including Esa Chen in Victoria, Lily Pham in New South Wales, Deanna Mill in South Australia, James Buckley in Queensland and Dana McLennan in Tasmania.

* 2021 pharmacy board registration data

Changing demographic profile

As Australia faces increasing challenges meeting the healthcare needs of an ageing population, the number of pharmacists has more than doubled in the past 20 years and the number of women has grown steadily in that period.

But while demand is high, pharmacy has a low growth rate compared with other Australian healthcare professions, according to a recent demographic study published in the International Journal of Pharmacy Practice.2 Both falling student numbers and changes to immigration policy have contributed to a low growth rate and an ageing of the pharmacist workforce when compared to other professions.

The study found that over the past 20 years there has been an increase in demand for pharmacists driven by an increase in dispensing volumes arising from Australia’s increasing and ageing population and factors including the introduction of non-dispensing services such as medication reviews as well as emerging career opportunities in aged care and general medical practice.

In 1999 47% of employed pharmacists were women, in 2012 women had risen to 57% of the profession and in the latest Pharmacy Board of Australia Registrant Data to March this year, that figure is now 63%. The ACT has the highest female ratio at 66.7% and Tasmania the lowest at 61.3%.3

A significant increase in the number of pharmacy graduates between 1997 and 2008 – and a three-fold increase in the number of pharmacy schools – resulted in pharmacists having a younger age distribution. By 2000 two-thirds of graduates were women.

Stewards of medicine safety

The evolution of pharmacists as the stewards of medicine safety can be seen today in support for population health initiatives such as vaccination, and a growing role in preventative health, medicines safety and clinical governance, according to PSA’s Pharmacists in 2023: roles and remuneration.4

Pharmacists, therefore, it states, need to be embedded wherever medicines are used and where decisions are made – ‘from the point of prescribing, through to supply and administration, and monitoring health outcomes’ – in both clinical care and non-clinical care roles.

PSA has led ground-breaking projects to put pharmacists on the ground in general practice, ACCHOs and residential aged care facilities (RACFs). It also provides training in emerging fields such as general practice pharmacy and administering medications by injection. As well, a PSA aged care training module will be available in the near future.

Emily Waddell MPS, 33, works in a multidisciplinary team with Goondir Health Services, seeing clients in Dalby, St George and Oakey and travelling with a mobile clinic to smaller communities in south-eastern and south-western Queensland. The health service has 5,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients and a footprint of 160,000 square kilometres.

Ms Waddell’s day-to-day team includes nurses, GPs, Aboriginal health workers and allied health coordinators and she is increasingly taking on governance responsibilities for the health service.

‘My role is really fulfilling and a great balance. I deliver one-on-one patient services on the ground for Home Medicines Reviews, medication reviews in the clinic, helping out with medication reconciliation after discharge, Webster pack updates, trouble-shooting, and then I have the opportunity to contribute to the organisation’s overarching medication and clinical governance,’ she said.

‘As pharmacists we are the medicine experts and we need to be involved in conversations about medication safety governance because we have the skills and the expertise.’

The job fulfils Ms Waddell’s commitment to equity in healthcare and her love of the bush, where she started her career as a hospital pharmacist in a small rural town. She was also part of the IPAC study (Integrating Pharmacists into Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services) to improve chronic disease outcomes in Indigenous communities.

‘A postcode should not make a difference to your health, so I see myself as working in medication safety in rural areas, in some shape or form, for the rest of my career,’ she says. ‘There are so many opportunities in rural and Indigenous healthcare to close the gap in health outcomes, and different approaches to tackle that big goal. I’ll never be bored.’

A rural career also appealed to Amelia Wood MPS who worked in the wine industry after school before studying pharmacy by correspondence at university and working as a pharmacy assistant.

‘These early career pharmacists are changing the practice profile in Australia and “redefining” the modern pharmacist.’

Ms Wood, 35, completed her intern year when her son was one and became accredited 2 years later when her daughter arrived. ‘I knew I wanted to be accredited as soon as possible to allow me some flexibility in how and when I worked, and to focus on clinical work,’ she says.

She works two mornings at a community pharmacy in Naracoorte, South Australia, and spends the afternoons conducting HMRs and Residential Medication Management Reviews. One day a week Ms Wood is employed as an embedded pharmacist at Longridge Aged Care residential facility in Naracoorte where she advises on medication management, mental health care plans, polypharmacy, psychotropic medicine reduction as well as staff education.

‘The work is more clinical and often involves me going away to research a topic or investigate alternatives to a medication or therapy. We have a great network of embedded pharmacists; it’s like a brains trust that can help with queries and we support each other,’ Ms Wood said.

The embedded aged care role, facilitated by PSA and funded by Country South Australia Primary Health Network, is a model recommended by the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety for all RACFs to protect residents from medicines harm.

PSA’s Medicine safety: take care report found that 98%, virtually all, residents in RACFs have experienced at least one medicine-related problem.5

‘My role has allowed me to establish relationships with the nursing staff, carers, doctors, physiotherapists and the residents themselves. It has also helped with communication to the community pharmacy,’ Ms Wood said.

‘I love the community pharmacy as it’s an opportunity to be part of a team and interact with the community but being an accredited pharmacist has allowed me to have a more balanced family and work life.’

Pharmacist-led interventions

The retention of ECPs is a key concern raised by PSA and the Monash University demographic study, which found pharmacists aged under 35 reported a decrease in their intention to remain working in pharmacy as measured by Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) surveys between 2013 and 2018. While the youngest cohort of pharmacists aged 20–34 is currently the largest, the next group aged 35–44 increased in number at a greater rate.

The Pharmacists in 2023: roles and remuneration report states that ECPs had identified artificial barriers that prevented them from better protecting patients from unnecessary harm from medicines, and were concerned that remuneration was not fair and reasonable for their skills and expertise.4

‘ECPs are further concerned there are inadequate opportunities that allow them to innovate, develop and diversify their practice,’ the report states.

Hayley Croft MPS has significantly diversified her practice since starting in pharmacy in Newcastle, NSW, where she has provided clinical pharmacy services to community patients since 2007. A PhD in Pharmacy led to an academic teaching and research career as a clinician scientist in multi-morbidity care focused on effective and safe use of pharmacotherapies for complex, chronic patients.

Since 2019, Dr Croft, 39, has been a Lecturer in Pharmacy at the University of Newcastle. Her teaching role is complemented by supporting undergraduate students conduct healthcare research, ‘knowing that this increases awareness of these opportunities for new graduates transitioning into practice’.

Key areas of interest are cardio-metabolic health, disability care and pharmacy practice and education, with a specialty in services for people with disability including those receiving care in supported independent living arrangements. ‘As an early career researcher my focus is on activities that highlight a role for pharmacists in both preventing medication-related harms for people receiving disability care and providing medicines support for their carers in the community,’ she said.

Her interest in this field was sparked when local pharmacists were approached by disability support workers to provide training about medicines. Dr Croft now works collaboratively with colleagues at Cognitive Pharmacist Consultants to develop an understanding of the day-to-day experiences of medicines for people with disability and their carers.

This includes swallowing difficulties, which she sees in her consultant work.

‘For some patients it is an iterative process of changing the drug, its formulation, and introducing medication lubricants to enable them to swallow their medicine.’

‘I would like to see pharmacists everywhere that medicines are. If they are given, prescribed, talked about – a pharmacist should be there.’

Dr Croft is motivated to engage in research ‘because there are limited pathways for people receiving and providing disability care to regularly access pharmacist-delivered services’.

She finds it ‘exciting’ to be developing ideas and an evidence base for tailoring the role and scope of pharmacists to areas where there is an unmet health need.

Her research pathway connects Dr Croft with other researchers and healthcare providers and, importantly, her students, the next generation of pharmacists.

She intends continuing her research training to explore opportunities that ‘more seamlessly’ connect patients at risk of medicines harm with pharmacist-led services and to advocate for more support, funding and recognition within the healthcare system.

Pharmacists, she points out, can communicate widely with those who use medicines. They can also be sensitive to the needs of specific patient groups, and look for opportunities – in transitions of care, for instance – to tailor their contemporary knowledge and medicines’ expertise to the way they deliver health services.

Moving between practice domains

Remaining career-long as a community or hospital pharmacist is another area of signficant change in the profession. Jumping between practice domains is far more common with ECPs.

As A/Prof Freeman points out: ‘Many have solidified themselves as leaders and mentors among their peers. They challenge the notions of the pharmacy profession, continuously innovating and inspiring those around them. And they are gaining considerable experience through exposure to a variety of practice environments and redefining what a modern pharmacist is.’

For instance, as a clinical pharmacist at Silver Chain In-home Aged Care services in Perth Ms Fulford works within an integrated team supporting people to receive end-of-life care at home, a role that includes managing transitions of care, chronic disease management, medication reviews and deprescribing.

In another role, as a general practice pharmacist at Street Doctor, a mobile GP clinic providing healthcare to people without regular housing including rough sleepers and also vulnerable Indigenous people, Ms Fulford provides medication advice to optimise prescribing, medication reviews, diabetes education and harm-minimisation counselling. And a further role for is a senior research assistant at the University of Western Australia where she is involved in a National Health and Medical Research Council study aimed at improving early detection and management of dementia in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

‘I would like to see pharmacists everywhere that medicines are. If they are given, prescribed, talked about – a pharmacist should be there,’ Ms Fulford says. ‘I have the opportunity to shape and grow my professional skills based on current gaps in the healthcare system.’

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Pharmacy labour force 1998. At: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/b3a48d3d-c8b8-4653-8b17-19e94774a6a8/plf98.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- Australian Government. Department of Health. 2019. Pharmacists. At: https://hwd.health.gov.au/resources/publications/factsheet-alld-pharmacists-2019.pdf

- Jackson JK, Liang J, Page AT. Analysis of the demographics and characteristics of the Australian pharmacist workforce 2013–2018: decreasing supply points to the need for a workforce strategy: Int J Pharm Pract 2021;29(2):178–85.

- Pharmacy Board of Australia. Pharmacy Board of Australia Registrant Data. At: www.pharmacyboard.gov.au/news/newsletters/march-2021.aspx#workforce-data

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. 2019. Pharmacists in 2023: roles and remuneration. Canberra: PSA. At: www.psa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/PSA-Roles-Remuneration-in-2023-V3_FINAL.pdf

- Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. 2019. Medicine safety: take care. Canberra: PSA.. At: www.psa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/PSA-Medicine-Safety-Report.pdf

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more