A new emergency response plan outlines Australia’s approach to containing COVID-19, as clusters of the novel coronavirus continue to emerge around the world.

There are now 81,002 confirmed cases across nearly 40 countries, including a recent surge in infections and fatalities in Italy, Iran and South Korea. Hubei, China remains the epicentre of the disease, with a reported 2,615 deaths.

The number of cases in Australia has jumped to 23, after eight passengers from the Diamond Princess cruise ship were repatriated from Japan. They were in quarantine with 170 other passengers in Darwin, where they tested positive for COVID-19, and have since returned to their home states for treatment.

Australia’s Chief Medical Officer Professor Brendan Murphy said there was currently ‘no reason for people to feel concerned’, but that the government was prepared should the situation change.

‘In Australia, there is no community transmission of this virus at present,’ he said on Monday.

‘We have a global pandemic plan, which is based on our pre-existing and long practised pandemic influenza plan, and we are certainly preparing as a nation for every eventuality.’

Key points

|

Pandemic plan

Dubbed the ‘COVID-19 Plan’, the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus outlines a strategy in the event of a large-scale coronavirus outbreak.

It comes as World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned the outbreak could become a global pandemic, which is defined by WHO as a disease spreading across two continents.

‘For the moment, we are not witnessing the uncontained global spread of this virus, and we are not witnessing large-scale severe disease or death,’ Mr Ghebreyesus said.

‘Does this virus have pandemic potential? Absolutely, it has. Are we there yet? From our assessment, not yet.’

The plan is based on the Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza and outlines three levels of impact: if clinical severity is low, moderate and high.

‘The novel coronavirus outbreak represents a significant risk to Australia,’ the document states.

‘It has the potential to cause high levels of morbidity and mortality and to disrupt our community socially and economically.’

If severity is low, the impact may be similar to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic or a severe seasonal influenza, with the majority of cases likely to experience mild to moderate clinical features.

Moderate severity would require surge staffing and alternate models of clinical care, such as the establishment of flu-like clinics, to cope with increased demands for healthcare.

The worst case scenario would see severe widespread illness challenging the capacity of the health sector. Areas such as primary care, acute care, pharmacies, nurse practitioners and aged care facilities would be stretched to capacity, and prioritisation would be essential within hospitals to maintain essential services.

Professor Lyn Gilbert, Senior Researcher at the Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Disease and Biosecurity, said strict infection control measures may not stop the virus from entering Australia, but they would slow it down, giving the health system time to mobilise.

‘Given no one in the population has encountered [this virus] before, everybody is pretty well susceptible, and could be a fairly big strain on the health system unless we are very well-prepared,’ she said.

The COVID-19 Plan emphasises the need for collaboration between health professionals, and between health professionals and state and federal governments, in order to deal with widespread infection.

‘Non-government parties, such as general practitioners, nurses and pharmacists will also be involved in responding to a pandemic,’ it states.

‘It is acknowledged that healthcare practices will rely on the hard work of teams of individuals to implement pandemic measures and that these teams will be made up of people with a broad range of skills.’

Australian advancement

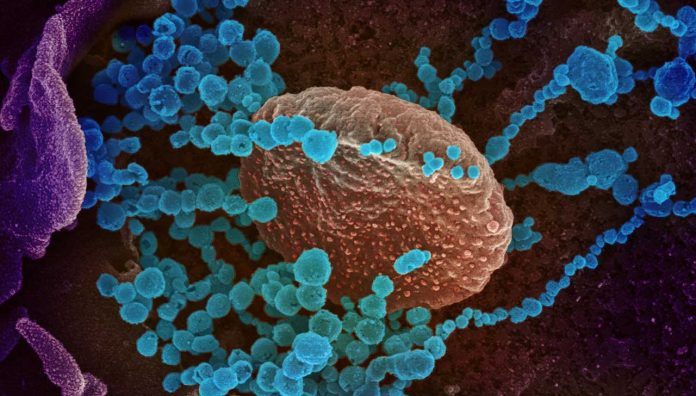

With clusters of COVID-19 emerging all over the world, with some showing no obvious link to China, experts are struggling to determine where they started and how they have spread.

‘The role of environmental contamination in the transmission of COVID-19 is not yet clear,’ a WHO situation report from Saturday said.

Chinese researchers have confirmed a case of presumed asymptomatic transmission: a 20-year-old woman from Wuhan, China. She is thought to have infected five family members without showing any symptoms herself.

Meanwhile, researchers from the University of Queensland (UQ) have created the first vaccine candidate for the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

It took just three weeks for the team of 20 to develop the candidate, which will now be developed further before formal pre-clinical testing.

The project was funded by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) rapid response program, and UQ Vice-Chancellor Peter Høj said the researchers had been working around the clock.

‘There is still extensive testing to ensure that the vaccine candidate is safe and creates an effective immune response, but the technology and the dedication of these researchers means the first hurdle has been passed,’ he said.

It comes after Australian researchers were the first outside China to successfully grow the virus in a lab.

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Sponsorship information

Sponsorship information

Talking to patients who have questions

Talking to patients who have questions