Highest risk travellers need additional support – from pharmacists.

Which of the following travel is highest risk to a person’s health?

A. An adrenaline-pumping adventure holiday in Queenstown, New Zealand.

B. Buck’s weekend in Bali.

C. Staying with family members in Sri Lanka for 3 months on long service leave.

D. A week visiting the ancient temples in Angkor Wat, Cambodia.

While each of these examples do have some risks, (C) is an example of VFR travel, which is generally considered much higher risk than travel to similar locations for primarily tourism or business purposes.

So why is this? And what is a VFR traveller?

We asked Associate Professor Holly Seale, a social scientist at the School of Population Health, University of New South Wales, what pharmacists need to know about this travel cohort and the unique risks they experience.

What is VFR travel?

VFR is a public health construct – “visiting friends and relatives (VFR)”. It categorises travellers who travel to lower-income countries for the purpose of visiting friends and relatives. Often these travellers are ethnically distinct from the majority population of the country of residence.

The definition of VFR has been updated in recent years, which requires:

- the intended purpose of travel is to visit friends or relatives

- an epidemiological gradient of health risk between the two locations based on an assessment of the determinants of health, including traveller behaviour, socioeconomic status, genetic-biological attributes, and environmental exposures.

This differs from previous approaches to VFR travellers based on indirect factors for health risk (e.g. administrative category of migrant, country of birth, destination), factors that may not be directly relevant to determining adverse health or disease outcomes.

Why are VFR travellers more at risk?

VFR travellers are more likely to:

- travel for longer periods of time

- travel to rural destinations

- make multiple return visits.

They often stay with family members or friends, have less control over their diets and are more likely to drink untreated water. The health risk gradient between the source and destination may also be influenced by:

- behaviour (e.g. choice of transportation mode, interpersonal body fluid exchanges, recreational alcohol/drug consumption)

- genetic or biological factors contributing to increased risk (e.g. innate immunity or preexisting health conditions)

- socioeconomic factors (e.g. educational attainment, willingness to pay for prevention services, and prescription drug compliance)

- environmental factors (e.g. availability of health services, public health infrastructure)

- prevalence of endemic or transmissible diseases.1

What are the main vaccine-preventable diseases of concern for VFR travel?

What are the main vaccine-preventable diseases of concern for VFR travel?

Previous studies have described VFR travellers at being at increased risk of malaria, traveller’s diarrhoea, intestinal parasites, typhoid, paratyphoid, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in comparison to tourists and business travellers.2

What are the main barriers to protecting people from vaccine preventable diseases ahead of VFR travel?

Barriers include:

- limited awareness of the need to be vaccinated

- misunderstandings about risk of disease due to assumptions about immunity based on past residence

- cost and accessibility factors, especially when vaccinations for travel are often not covered by public health systems or travel insurance

- complex travel plans, including visits to locations with limited epidemiology data on disease health literacy barriers.

Additionally, VFR travel is often booked late, so the time period between booking and flying often limits the ability to fit in multi-dose vaccines. It also means there is insufficient time for recommended vaccinations or boosters to become effective.

Sometimes it’s also a system barrier. GPs who consult in a language other than English, were less likely to consider VFR travellers at higher risk compared with holiday travellers. These GPs may be VFR travellers themselves and therefore subject to the same cultural perceptions of risk as other VFR travellers.3

How can immunisers (including pharmacists) more effectively engage with people regarding vaccination ahead of VFR travel?

With a low perception of risk and inadequate pre-travel health-seeking behaviour, an opportunistic approach to provision of pre-travel health advice to VFR travellers is required.

Opportunistic conversations about travel, especially among immunisers who may share a common language, may assist with identifying future travel plans and provide more time for fitting in vaccination.

Undergoing advanced training in travel medicine, will also support understanding about vaccine recommendations, travel risks and destinations etc.

Resources for pharmacists

- Smartraveller: www.smartraveller.gov.au

- (Interim) Australian Centre for Disease Control: [Provides health alerts.] At: www.cdc.gov.au

- World Health Organization. At: www.who.int

- Choice: Travel insurance buying guide. At: www.choice.com.au/travel/money/travel-insurance/buying-guides/insurance

Our author

Associate Professor Holly Seale is a social scientist researching social and behavioural factors impacting engagement with infectious disease prevention strategies at the University of New South Wales.

Declared interests

Holly Seale is an investigator on research studies funded by the NHMRC and has previously received funding from NSW Ministry of Health, as well as from Sanofi Pasteur, Moderna and Pfizer for investigator-driven research and consulting fees.

References

- Behrens RH, Stauffer WM, Barnett ED, et al. Travel case scenarios as a demonstration of risk assessment of VFR travelers: introduction to criteria and evidence-based definition and framework. J Travel Med 2010;17(3):153–62. At: https://academic.oup.com/jtm/article/17/3/153/1803997?login=true

- Heywood AE, Zwar N, Forssman BL, et al. The contribution of travellers visiting friends and relatives to notified infectious diseases in Australia: state-based enhanced surveillance. Epidemiol Infect 2016;144(16):3554–63. At: www.cambridge.org/core/journals/epidemiology-and-infection/article/contribution-of-travellers-visiting-friends-and-relatives-to-notified-infectious-diseases-in-australia-statebased-enhanced-surveillance/9B269DB6B7B047800CDBF7C7349100C9

- Heywood AE, Forssman BL, Seale H, et al. General practitioners’ perception of risk for travelers visiting friends and relatives. J Travel Med 2015;22(6):368–74. At: https://academic.oup.com/jtm/article/22/6/368/2635583?login=true

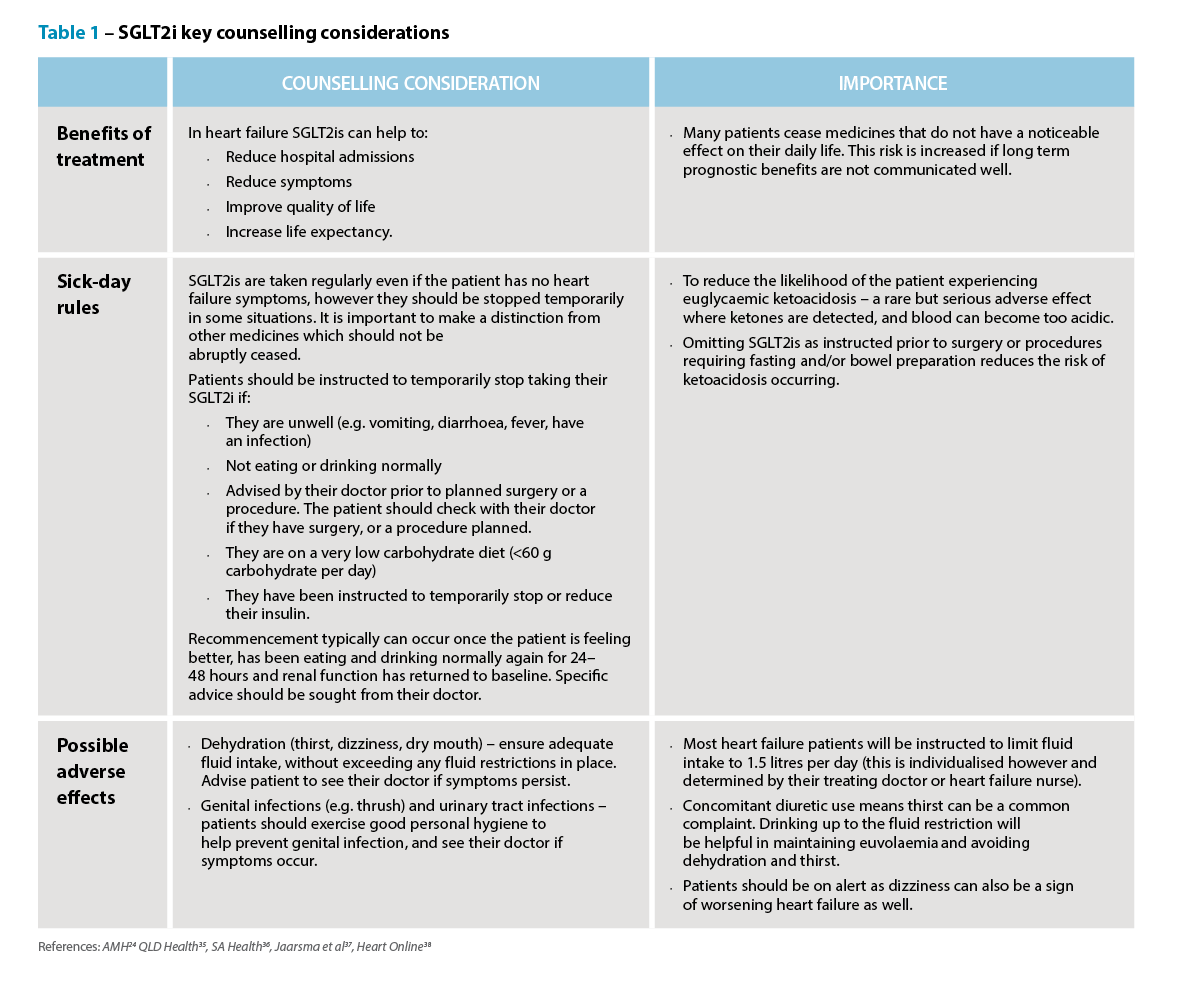

Categorisation of heart failure

Categorisation of heart failure A focus on SGLT2is

A focus on SGLT2is Knowledge to practice

Knowledge to practice

Professor Anthony Lawler, Australian Government Chief Medical Officer,

Professor Anthony Lawler, Australian Government Chief Medical Officer,

This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

This CPD activity is supported by an unrestricted education grant by Reckitt.[/caption]

Case scenario

Case scenario