It reads like the opening of an Agatha Christie murder mystery: ‘In the hot summer months of 19th century colonial Australia, a quiet dread descended upon parents of the very young.’ But Dr Lynette Finch’s sentence is not fiction.

As the University of the Sunshine Coast academic notes, historical records indicate that ‘summer diarrhoea’ caused between a quarter and half of all infant deaths between 1875 and 1900.1

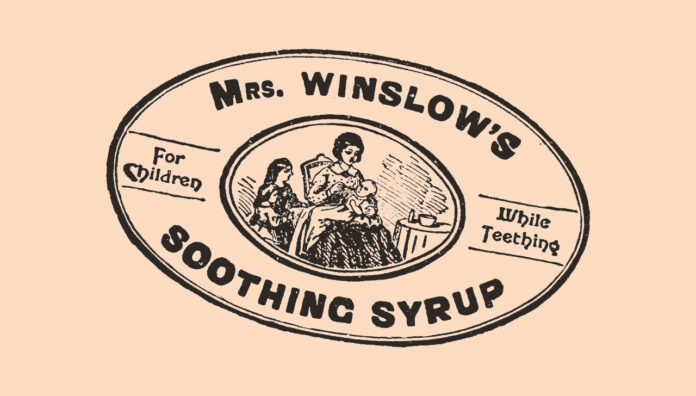

Those anxious parents turned to so-called patent medicines to soothe sick babies. ‘So-called’ as few of the ready-to-use products held patents. Big sellers for pharmacies, food stores and doctors included Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, Atkinson’s Royal Infants Preservative, and Woodward’s Gripe Water. Steedman’s Soothing Powders and its knock-off rival Stedman’s Teething Powders were particular favourites.1–3

Soothed or subdued

What mothers did not know, or notice, were the products’ ingredients. Manufacturers were not required to list them. At the top of the unlisted list were opiates such as opium and morphine. Alcohol and mercury were also common.1,3,4,8,9

Further, advertisements like the following in Queensland’s Maryborough Chronicle encouraged carers to dose generously: ‘For a child under one month old, 6–10 drops; three months old, half a teaspoonful; and six months old and upwards, a teaspoonful 3 or 4 times daily’. The medicine, Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup, contained morphine and alcohol.3,8

Little wonder infants worldwide were ‘soothed’. In mid-19th century Britain, for instance, working mothers often relied on patent medicines.

So, too, did nurses tending more than one baby. English apothecary John Quincy wrote disapprovingly of this practice: ‘A very mischievous way some nurses have got, of giving their children this medicine to make them sleep, more for their own ease than anything else.’3

Many maladies

Patent medicines were popular globally throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, and not just for diarrhoea. Infants suffering from malaria, gastrointestinal disorders, colic and yellow fever were treated with the remedies.1,2,4

Teething was considered dangerous, even deadly. Advertisements and promotional material built on this anxiety. Mothers were encouraged, even shamed, into purchasing patent medicines.7,9,11

As stated in a booklet for mothers, produced by John Steedman and Company, teething was viewed as among the ‘most perilous transitions’ in the 19th century. It was ‘linked to insomnia and drooling, deafness and epilepsy’.1–3,7

Mercury was a popular ingredient in teething powders (and other children’s medicines) at the time. As its use grew, so too did ‘pink disease’ (or infantile acrodynia), a syndrome associated with mercury poisoning. Among many serious symptoms, the most famous was the marked reddening of the hands and feet. 4–6,10

Raising the alarm

It is unsurprising that accidental deaths occurred. By the mid-19th century, doctors began raising the alarm. As Henry Chavasse wrote in 1860, ‘all quack medicines should be banned from the nursery’.1,3,8

Back in Queensland, coroners’ reports from 1859 to 1900, analysed by Dr Finch, highlight the risk patent medicines posed. In the 1880s alone, they were implicated in 15 of the 98 infant deaths from ‘sickness’.1

Gradually, dangerous ingredients were outlawed worldwide. Still, it was not until 1953 that John Steedman and Company announced it had removed mercury from its 140-year-old formula. And alcohol was not removed from Woodward’s Gripe Water until … 1992.2–5,12

References

- Manvi S, Sharma R. Tincture Benzoin in Dermatology. Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Research 2017;05(8):26154–8.

- Sedgwick RR. Ward, Joshua (1685-1761). The History of Parliament. The History of Parliament Trust 1964–2020.

- Westminster Abbey. Joshua Ward: physician and doctor. Dean and Chapter of Westminster. 2024.

- Museum of Health Care at Kingston. Friar’s Balsam (Compound Tincture of Benzoin). 2024.

- Moussaieff A, Fride E, Amar Z, et al. The Jerusalem Balsam: from the Franciscan Monastery in the old city of Jerusalem to Martindale 33. J. Ethnopharmacol 2005;101(1–3):16–26.

- The IK Workshop Society at The IK Foundation. iFACTS Fredrik Hasselquist. The IK Foundation & Company. 2024.

- Murden S. Dr Joshua Ward, the ‘Friar’s Balsam’ man. Georgian Medicine and Health. 2021.

- WebMD. Benzoin – uses, side effects, and more. Therapeutic Research Faculty 2020.

- Grimshaw J, Bayton R, Elliott A. Styrax L. Trees and Shrubs Online. 2017.

- WebMD. Storax – uses, side effects, and more. Therapeutic Research Faculty 2020.

- AlphaSport. Friars Balsam 25ml. Alpha Vital 2024.

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Gold Cross Friar’s Balsam (330993). 2020.

- Chemist Warehouse. Gold Cross Friars Balsam. Chemist Warehouse Virginia QLD.

- WebMD. Benzoin Tincture Plain – uses, side effects, and more. Therapeutic Research Faculty 2020.

- Jeffery SL. Advanced wound therapies in the management of severe military lower limb trauma: a new perspective. Eplasty 2009;e28.

- Ray RK, Aung H, Corbett SA. Cost-effective traction for arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Open J. Orthop 2014;4(05):130–6.

- Scovil ER. Notes from the medical press. J Nurs 1913;13(9):703–5.

- Wikipedia. Friar’s Balsam (horse). 2023.

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Sponsorship information

Sponsorship information

Talking to patients who have questions

Talking to patients who have questions