While opioid deprescribing can prevent severe adverse effects, it’s not appropriate for all patients. Creating a tailored, individualised approach is the key to a successful outcome.

Opioids are prescribed for pain on a large scale in Australia, with 1.9 million Australians initiated on the medicines each year.

‘Around 95% of people use opioids acutely,’ said Associate Professor Carl Schneider from the University of Sydney’s School of Pharmacy. ‘However, [one in 20] go on to use opioids chronically.’

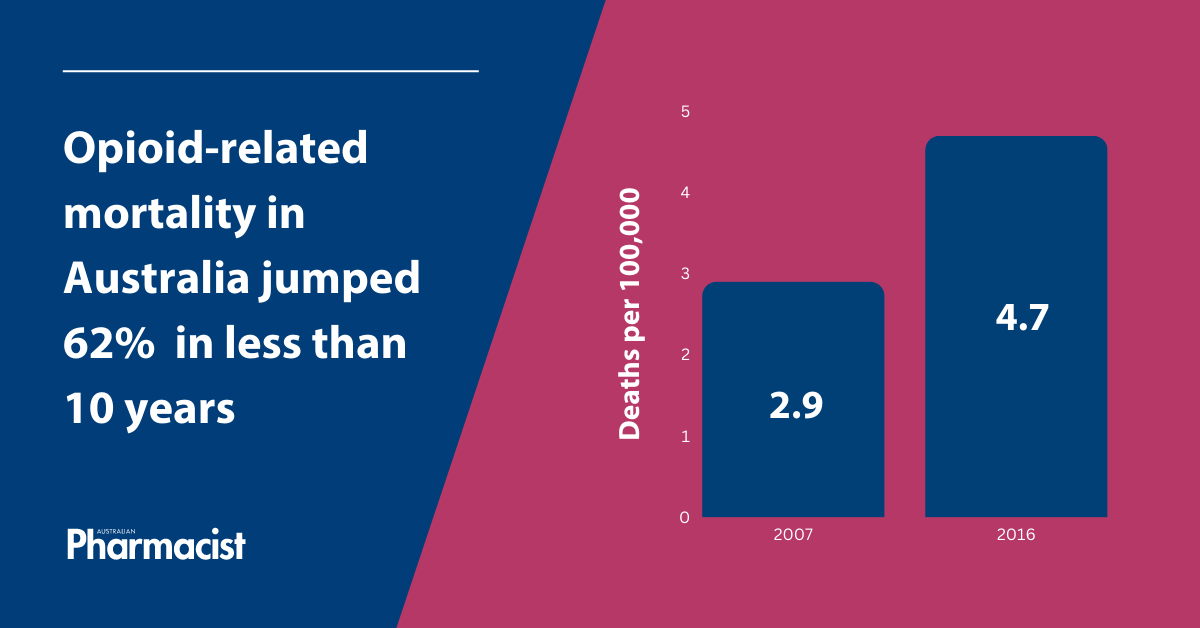

Increased or chronic use heightens the risk of adverse effects, including opioid toxicity and overdose. Opioid-related mortality in Australia jumped 62% from 2007–2016 from 2.9 to 4.7 deaths per 100,000 population, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the population.

Increased or chronic use heightens the risk of adverse effects, including opioid toxicity and overdose. Opioid-related mortality in Australia jumped 62% from 2007–2016 from 2.9 to 4.7 deaths per 100,000 population, after adjusting for differences in the age structure of the population.

However, guidelines tightening the use of opioids to curb these risks can also be problematic.

‘In 2016, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States put out guidelines for pain management recommending reduction or discontinuation of high-dose opiates, which led to unintended consequences, such as an increase in suicide post-cessation,’ said A/Prof Schneider.

This led a team of University of Sydney pharmacists, multidisciplinary and consumer stakeholders to develop Evidence-based Guidelines for Deprescribing Opioid Analgesics, providing guidance on deprescribing from opioids for adults with pain in a safe and effective manner. The 11 recommendations focus on when, how, and in what situation it may be appropriate to reduce opioid use, with a central focus on individualised care.

‘A key principle in the guidelines is undertaking shared decision making, which provides the means for patient empowerment,’ said A/Prof Schneider. ‘We know empowered patients are able to make better choices about healthcare.’

A plan for deprescribing from the start

Pharmacists are involved in the vast majority of opioid initiations, providing ‘tremendous’ potential for managing the use of these medicines, said A/Prof Schneider.

A tailored approach to therapy should be laid out when patients are initiated on opioids, including duration of use, monitoring effectiveness, and plans around deprescribing and/or when to trial a reduction.

At the point of dispensing, pharmacists should ask patients:

- What did the doctor tell you to expect from this therapy?

- How have you been advised to take it?

- How long did the doctor say you’ll be taking this medicine for, and under what circumstances?

‘That way, you’re nudging the person into considering that this may not be a long-term therapy,’ said A/Prof Schneider. ‘Introducing that concept as an expectation can be meaningful at a population level.’

When to deprescribe

For patients with chronic pain, who may be one of the 5% of people using opioids long term, the guidelines suggest initiating deprescribing when:

- there is a lack of clinically significant improvement in function, quality of life or pain

- therapeutic goals aren’t met

- patients experience serious or intolerable opioid-related adverse effects.

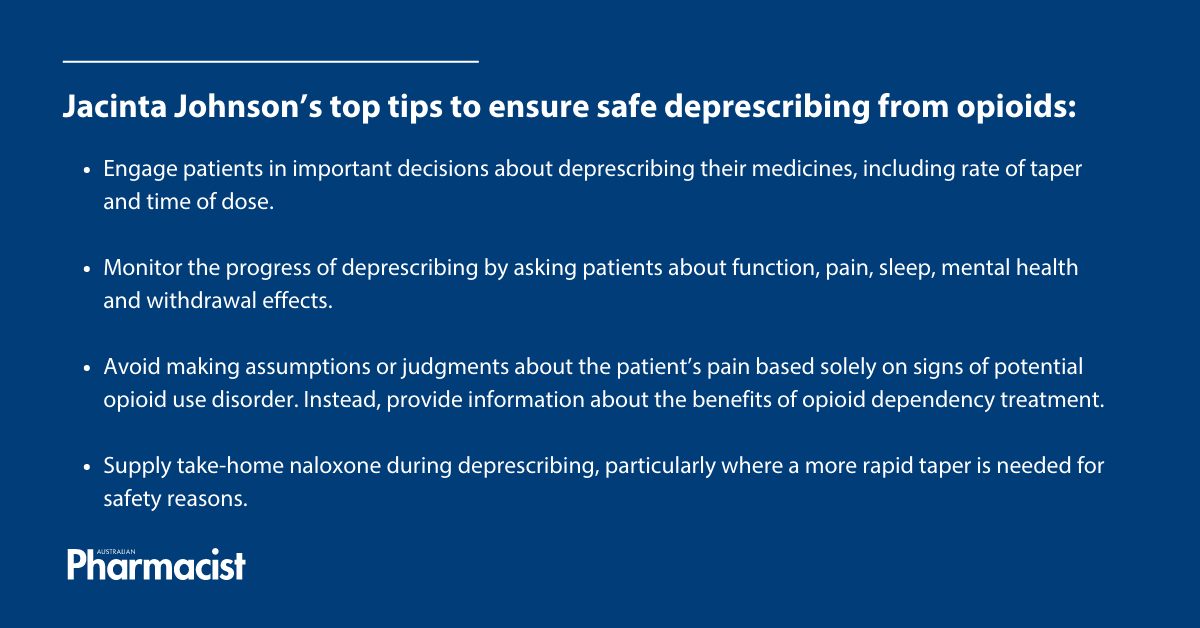

Opioids should never abruptly cease without gradually reducing the dose or transitioning to different treatments. When starting the deprescribing process, it’s crucial to establish open and non-judgmental communication, fostering a trusting relationship to gain insight into the patient’s goals and concerns, said Advance Practice Pharmacist Dr Jacinta Johnson MPS.

Pharmacists can directly engage in discussions with patients about important decisions, such as:

- which medicines will be decreased first

- the rate of taper

- timing of doses.

‘This patient-centred approach helps ensure the deprescribing plan is tailored to meet the individual’s specific needs and preferences, which is likely to lead to a more successful outcome,’ she said.

Not for all patients

Opioid deprescribing is not a one-size-fits-all approach, and may not be appropriate for every patient. The guidelines suggest opioid deprescribing should be avoided in:

- patients nearing the end of life unless clinically indicated

- those with severe opioid use disorder.

With the fast-acting, well-tolerated Ordine (morphine) solution set to be discontinued by years’ end, palliative care patients may be forced to consider other pain solutions.

‘Any shortage or removal of a drug from the market leaves those using that medicine in a situation where they need to have a conversation with the prescriber to establish a shared outcome,’ said A/Prof Schneider. ‘Patients nearing end of life are a population in which deprescribing is not appropriate, so it would be a case of trialling a substitute therapy, typically an opioid.’

In patients with opioid use disorder, deprescribing can increase risks of opioid-related harms. Signs and symptoms of severe opioid use disorder include:

- taking larger amounts or taking opioids for a longer period than intended

- unsuccessful attempts to reduce opioid use

- cravings, strong desires or urges to take opioids

- continuing to take opioids despite physical, psychological or social/interpersonal problems that have likely been caused or worsened by opioid use.

Patients with severe opioid use disorder might be better suited to the Opioid Dependence Treatment Program. However, it’s essential pharmacists approach these situations with sensitivity and compassion, said Dr Johnson.

‘We need to avoid making assumptions or judgments about the patient’s pain based solely on signs of potential opioid use disorder,’ she said.

Pharmacists should provide information about opioid dependency treatment and the benefits it can bring, explaining the relevant local process for accessing services.

‘This could include making an appointment with their GP or directly contacting local drug and alcohol services.’

Monitoring, review and cointerventions

Intervals for review to assess progress towards agreed goals should be documented as part of the deprescribing plan, said Dr Johnson. Pharmacists can assist with monitoring by checking in with patients informally or using validated tools regarding:

- function

- pain

- sleep

- mental health

- withdrawal effects.

‘Pharmacists should communicate as needed with other healthcare providers involved in the patient’s care to collaborate on any required adjustments to the deprescribing plan based on the patient’s progress and needs,’ said Dr Johnson.

Co-interventions can facilitate deprescribing, including referrals to acupuncturists, physiotherapists or psychologists.

‘It’s a case of having a holistic therapeutic plan as part of the opioid deprescribing process – including formal steps for initiation of other non-pharmacological treatments,’ said A/Prof Schneider.

However, a key co-intervention pharmacists should consider during deprescribing of opioids is supply of take-home naloxone (learn more about saving a life with naloxone by undertaking PSA’s recent CPD). ‘This is particularly important for patients where a more rapid taper or cessation is needed for safety, for example in someone who has experienced toxicity on their current dosage,’ said Dr Johnson.

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more