td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28946

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-18 15:51:52

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-18 04:51:52

[post_content] => Around 4 million Australians (16% of the population) are living with back problems, with about 4 out of 5 people experiencing low back pain at some point in their lives.

Antidepressants are widely prescribed for low back pain and sciatica, with up to one in seven Australians with low back pain dispensed an antidepressant – most commonly the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline.

However, there is inconsistency across international clinical guidelines around their use for this indication, said Michael Ferraro, lead author of a review into Antidepressants for low back pain and spine‐related leg pain and Doctoral candidate at the Centre for Pain IMPACT, NeuRA, and the School of Health Sciences UNSW.

‘These medicines are very widely used clinically for sciatica, but there's barely any trial evidence to inform their use.'

Michael Ferraro

‘The general thought was that they might be useful in some patients,’ he said. ‘At an individual prescriber level, clinicians are more likely to prescribe an antidepressant as a second-line treatment, particularly where there might be issues with sleep or mood.’

The review looked at the effects of any antidepressant class – including serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants – on low back pain or spine-related leg pain (encompassing full nerve compression or referred pain into the leg).

While not all patients with low back pain have spine-related leg pain, those who do generally have worse pain and poorer long-term outcomes, Mr Ferraro said.

‘These medicines are very widely used clinically for sciatica, but there's barely any trial evidence to inform their use,’ he said.

One class of antidepressant is beneficial for low back pain

The main outcomes of the review were impacts on patient-reported pain intensity, adverse events and function 3 months after initiation of treatment – enough time for the medicine to have a therapeutic effect.

The review is an update of an older Cochrane review, published in 2008, with the newer review incorporating results from industry-sponsored trials that tested the SNRI duloxetine.

‘Those trials, which were run across multiple international sites and recruited large patient populations, focused on low back pain patients,’ Mr Ferraro said.

While the review found that only SNRIs were effective over placebo for low back pain intensity, this effect was marginal.

‘When we think about the average effect in the patients that received an SNRI versus those who received the placebo, there was only a difference of around five points out of 100,’ he said.

‘That's what we would consider small, and it might even be so small that it's not really a benefit that your average patient would appreciate.’

Another antidepressant helps for disability

While the evidence is uncertain on the impact of SSRIs for low back pain or spine-related pain, tricyclic antidepressants were found to have no effect on pain.

However, there was one unexpected benefit unearthed.

‘They had a small effect on disability,’ Mr Ferraro said. ‘Normally we would expect any effects on disability to be mediated via pain, so that was a little surprising.’

But to demonstrate clinical benefit, there should be evidence of effects on both pain and disability, he said.

Antidepressants probably do more harm than good in back pain

The review found a lack of evidence to determine whether use of SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants for low back pain and spine-related leg pain lead to adverse events.

However, there was an increased risk of experiencing any adverse event when using SNRIs.

‘While we didn’t look at adverse events formally, nausea, dry mouth and dizziness – the typical effects you'd have with an antidepressant – would be the ones that are most likely,’ Mr Ferraro said.

The next step for the research team is further investigation into the effects of SNRIs for spine-related leg pain.

‘Members of the author team are about to commence recruitment for a randomised trial of duloxetine for spine-related leg pain or sciatica, Mr Ferraro said. ‘That will be a critical study, as it will be large enough to fill the evidence gap we identified.’

Should antidepressants still be prescribed for this indication?

Cessation of antidepressants, including tapering too quickly, can come with withdrawal effects. So should patients be initiated on a treatment that could have little or no benefit, with the potential for adverse events down the line?

‘None of the trials we included in the review actually assessed adverse events after the treatment had ceased, so that's a really key research item that must be addressed in the future,’ Mr Ferraro said.

However, when prescribing or dispensing antidepressants for low back pain or sciatica, it’s important to point patients to evidence that the benefits, on average, are small and may not be appreciable.

‘[Pharmacists and GPs] should explain that there’s a risk of side effects – and extrapolating from other data sources – that some of those effects may be related to tapering an antidepressant if it's not effective.’

Pharmacists are also advised to check in with patients to see how they are coping with their pain.

‘The evidence we included found a benefit [of SNRIs] within 14 weeks, after a course of 2–3 months,’ he said. ‘So if there's no benefit within the first 3 months, it would be critical to have a discussion with the pharmacist and then the GP.’

What are the alternative treatment options?

In terms of pharmacological treatments, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard recommends non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for patients with low back pain who are at low risk of NSAID-related harm.

Along with antidepressants, anticonvulsants and benzodiazepines should generally be avoided – with the risks outweighing the benefits and little evidence for their effectiveness. Opioid analgesics should only be considered in carefully selected patients, using the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration.

Overall, medicines should be used judiciously, with physical and psychological interventions recommended first line to improve function.

[post_title] => Antidepressants show little to no benefit for low back pain and sciatica

[post_excerpt] => New major review finds that antidepressants used for back pain and sciatica can cause more harm than good.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => antidepressants-show-little-to-no-benefit-for-low-back-pain-and-sciatica

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-03-19 15:58:36

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-19 04:58:36

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28946

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Antidepressants show little to no benefit for low back pain and sciatica

[title] => Antidepressants show little to no benefit for low back pain and sciatica

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/antidepressants-show-little-to-no-benefit-for-low-back-pain-and-sciatica/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28951

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28935

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-17 12:46:47

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-17 01:46:47

[post_content] => Several women’s health medicines will be on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) after new PBAC recommendations.

The listings are in addition to the government’s $573 million women’s health funding announcement last month.

Australian Pharmacist takes a look at these new additions and the impact cheaper medicines will have on women across the nation.

Funding for first ever progesterone-only contraceptive pill

From 1 May, Slinda (drospirenone) – a first-of-its-kind progesterone-only oral contraceptive pill OCP – will be available under the PBS.

Around 80,000 women are paying privately for Slinda, which costs around $80 for 3 months’ supply.

Under the PBS, the medicine will only set women back $31.60 ($7.70 for concession card holders) for 4 months’ supply.

The move will widen birth control options for Australian women, particularly those who can have difficulty with oestrogen-based OCPs

Dr Terri Foran, Sexual Health Physician said Slinda is particularly suitable for women who:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28721

[post_author] => 8289

[post_date] => 2025-03-17 12:30:51

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-17 01:30:51

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_28925" align="alignright" width="292"] Sponsorship information

Sponsorship information

This educational activity was managed by PSA at the request of and with funding from GSK, Sanofi and CSL Seqirus.[/caption]

Kushal is a 16-year-old male who missed his dTpa vaccination in 2021 due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neither Kushal nor his mother fully understand the importance of vaccination or the diseases that this vaccine protects against.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Already read the CPD in the journal? Scroll to the bottom to SUBMIT ANSWERS.

Immunisation has reduced disease, disability and death from 26 infectious diseases. While Australia has a relatively high immunisation coverage by global standards, there are opportunities for improvement, particularly in the adolescent cohort. Reduced vaccination uptake in young people has consequences for their future health status as well as the health of the Australian population.

The World Health Organization considers immunisation to be the most effective medical intervention available to prevent death and reduce disease in our communities. Since routine immunisations of infants were introduced in Australia in the 1950s, death or disability from many once-common infectious diseases is now rare.

All vaccines currently used in Australia offer enough protection to prevent disease in most vaccinated individuals. However, high rates of immunisation are essential to protect the population from preventable diseases.

The NIP aims to increase national immunisation coverage to reduce vaccination-preventable diseases by administering immunisations at specific times throughout a person’s life. Free vaccines on the NIP are available to people who hold or are eligible to hold a Medicare card, including adolescents. Free catch-up vaccinations are also provided to people if they are missed for any reason. The National Immunisation Program Vaccinations in Pharmacy (NIPVIP) Program was introduced on 1 January 2024 and allows eligible patients to receive free NIP vaccines in a community pharmacy, which makes vaccination accessible and affordable. On 29 April 2024, the program expanded to include off-site vaccinations in residential aged care and disability homes, enabling pharmacies to claim payments for administering NIP vaccines in these settings.

The NIP Schedule outlines recommended vaccines and schedule points.

Adolescent vaccines protect against five key diseases.

Diphtheria

Diphtheria is a serious bacterial disease that primarily affects the nose and throat and can cause skin infections. It is spread through coughing and sneezing or direct contact with infected wounds or contaminated objects. Toxins released by the bacterium may cause a membrane to grow across the throat or windpipe, potentially leading to airway obstruction, making breathing difficult. If the membrane completely blocks the airways, the patient can suffocate and die. The disease can also cause systemic complications, including myocarditis and neuropathy. Due to high rates of vaccination, diphtheria is rare in Australia.

Tetanus

Tetanus is caused by Clostridium tetani bacteria found in soil and animal faeces, which can affect the nerves in the brain and spinal cord. Bacteria can enter the body through a wound (particularly dirty or deep wounds) or a bite. The infection can lead to severe muscle spasms, particularly in the neck and jaw (lockjaw). Around 10% of people who get tetanus will die, with babies and older people having the highest risk of death.

Tetanus is now rare in Australia due to vaccination rates, although it mostly occurs in older adults who are not adequately vaccinated.

Pertussis

Pertussis (whooping cough) is a highly contagious bacterial respiratory infection caused by Bordetella pertussis, spread through coughing or sneezing. It can lead to severe coughing fits, difficulty breathing, pneumonia, brain damage and sometimes death. Despite the availability of vaccines for more than 50 years, pertussis remains a challenging disease to control as immunity wanes over time. Pertussis is especially serious for babies, but it can affect people of any age. It is always circulating in the community and epidemics occur in Australia every 3–4 years. There is currently a pertussis epidemic in Australia.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

HPV is a group of viruses spread through sexual contact. HPV is responsible for almost all cases of genital warts and cervical cancer. It can also lead to cancer of the anus, vagina, vulva and penis. Since the introduction of HPV vaccination in 2007, there has been a steady decline in high-grade cervical abnormalities in younger women. Research shows that widespread use of the HPV vaccine dramatically reduces the number of women who will develop cervical cancer. The Australian target of vaccinating 90% of all eligible people against HPV is one of three pillars in the Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative to achieve cervical cancer elimination by 2030.

Men who have sex with men (MSM) may be disproportionally at risk of HPV infection and associated diseases. This cohort may be up to 20 times more likely to develop anal cancer and 2–3 times more likely to develop genital warts compared with heterosexual males.

Males born before 1999 may not previously have been offered the HPV vaccine and may derive little herd benefit from the vaccination of females.

Prevention of HPV infection is important as there is currently no routine screening program for early detection of anal cancer.

Meningococcal ACWY

Meningococcal disease is a serious infection caused by Neisseria meningitidis, commonly referred to as meningococcus. Serogroups A, B, C, W and Y most commonly cause the disease and are transmitted in secretions from the back of the nose and throat, generally through close and prolonged contact. Meningococcal disease can develop quickly and is a medical emergency as it can be fatal within hours without treatment. Since the introduction of the meningococcal ACWY vaccination, the incidence of meningococcal disease has reduced, and the overall rate of invasive meningococcal disease fell to 0.3 per 100,000 in 2021.

The NIP provides a series of immunisations for adolescents, which are primarily delivered through school-based vaccination programs and other health services, including pharmacies.8

Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (dTpa)

Adolescents aged 11–13 years (Year 7) should receive a booster dose of combined diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (dTpa) reduced-antigen vaccine. A booster dose is required as pertussis immunity wanes after the childhood primary series, the last vaccine being administered at 4 years., Fully vaccinated adolescents will be protected from these diseases for many years, although they may need a tetanus or pertussis booster in the future. Adolescents should receive one dose of pertussis-containing vaccine, regardless of the number of previous doses they received before 10 years of age.26

Two dTpa vaccines are available: Boostrix and Adacel. Both are in 0.5 mL pre-filled syringes and are administered as an intramuscular injection (IMI) into the deltoid muscle of the upper arm.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

Adolescents are recommended to receive the 9vHPV (9-valent HPV) vaccine starting from age 9. However, the optimal age is 12–13 years (Year 7).30

Gardasil 9 is the adolescent HPV vaccine available on the NIP from age 12–13 years with a recommended single-dose schedule for those who are not immunocompromised. Free catch-up vaccinations are offered up to and including 25 years of age.30

Meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY)

It is recommended adolescents aged 14–16 years (Year 10) receive one dose of meningococcal ACWY vaccine. MenQuadfi is the vaccine available on the NIP for adolescents aged 14–16 years.31 Meningococcal ACWY vaccine comes in a pre-measured 0.5 mL dose and is given as an IMI, usually in the deltoid muscle.32 Catch-up immunisations for meningococcal ACWY are free for eligible people under 20 years old under the NIP.

Patients who are not eligible under the NIP can access them privately, by paying a fee. If they have private health insurance, they may be able to claim a rebate, depending on their policy and coverage.

Immunisation uptake in adolescents declined in 2023 when compared with 2022.2

In 2023, 85.5% of adolescents turning 15 years received the dTpa adolescent booster dose compared to 86.9% in 2022.

In 2023, 84.2% of Australian girls had received at least one dose of HPV vaccine by 15 years of age, down from 85.3% in 2021; 81.8% of boys had received at least one dose, down from 83.1%.

Coverage of an adolescent dose of meningococcal ACWY vaccine in adolescents turning 17 years in 2023 was 72.8%, compared with 75.9% in 2022.

Coverage rates for all types of vaccines in First Nations adolescents were lower than rates for non-First Nations adolescents, while adolescents in lower socioeconomic areas had lower immunisation rates than those from higher socioeconomic areas. These differences may be a result of a lack of accessibility due to location, fewer financial resources, or lower rates of education and health literacy.

The decrease in immunisation uptake in Australian adolescents is due to several factors, one of which is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lengthy school closures in some jurisdictions during 2020 and 2021 that disrupted school-based immunisation programs during that time have been well documented.2

In addition, COVID-19 has led to a change in attitude towards immunisation. People, particularly parents, are asking more questions, and increasing levels of concern about vaccinations are evident.33 Furthermore, lack of parental support and consent for vaccination means that vaccine uptake in young people (aged 12–17 years) continues to be a challenge.3

Lagging vaccination rates are also attributable to accessibility factors, including distance to a vaccination provider, available appointments, and costs involved in vaccination, such as doctor visits, and the need to take time off work or put other children into care to attend doctor appointments.2

Catch-up vaccinations aim to provide the best protection against vaccine-preventable diseases as quickly as possible by completing a person’s recommended vaccination schedule. Catch-up vaccinations should be offered to all adolescents who have not received the vaccines scheduled in the NIP and should be administered according to age-appropriate guidelines in the Australian Immunisation Handbook. Free catch-up vaccines are available for missed vaccines under the NIP until the age of 20, except for the HPV vaccine which is available up to and including age 25.8 Pharmacists can administer these vaccines.

Research shows pharmacists are uniquely positioned to increase vaccination coverage rates among adolescents and other eligible populations.34 Pharmacists can identify individuals who have missed vaccinations by checking the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) and ensuring they are offered catch-up immunisation. They can advocate for and encourage vaccination in adolescents, and appropriately trained pharmacists can administer immunisations.35

Community pharmacists are among the most trusted and respected health professionals across Australia.36 Pharmacists have been administering vaccinations since 2014, and it is widely accepted across all states and territories that vaccination is within the scope of practice for appropriately trained pharmacists. Through proactive discussions within the pharmacy environment, pharmacists are in a prime position to boost adolescent immunisation rates.

Pharmacists should ascertain vaccination status in adolescents to facilitate conversations around immunisation.

Ascertaining vaccination status

Check the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR)

Pharmacists should routinely check prior immunisation history on the AIR when dispensing prescriptions. If the adolescent is overdue for their vaccination, this can be mentioned when giving them their medication and a discussion initiated. Running AIR reports in advance (e.g. AIR10A Due/Overdue Report) for regular patients or certain cohorts may provide greater efficiencies. This could be particularly helpful if pharmacists wish to run vaccination clinics to coincide with various health awareness campaigns, (e.g. World Immunisation Week or National Meningococcal Week).

Vaccination status on the AIR must be checked before administering any vaccine, and any vaccines administered must be recorded on the AIR.35

Ask about immunisation history

During general conversations, pharmacists can ask about immunisation history and explain that the pharmacy offers catch-up vaccinations for those who need them. Pharmacists should also offer to check the AIR if the patient is unsure about their immunisation status.

Initiate conversation

Pharmacists who have identified adolescents behind in their scheduled immunisations should initiate a conversation about a catch-up immunisation. The goals of these discussions will depend upon the patient’s attitude towards vaccination.37

Talking to patients who are ready to vaccinate

The goal of the consultation is to prevent hesitancy and support timely vaccination. People who are ready to vaccinate tend to trust medical advice. However, as many as half will have questions about vaccination.38 Ensure patients feel confident to ask questions without judgement. Some in this cohort say they are concerned providers will think they are ‘antivaxxers’ if they ask questions about vaccination.39 The following actions are recommended40:

Talking to patients who have questions

Talking to patients who have questions

The goal of the consultation is to vaccinate and increase vaccine confidence. Some people report feeling they are not sufficiently informed to agree to vaccination confidently, while some need permission to express and explore their concerns.38 It is recommended you:

The goal of the consultation is to maintain trust and engagement and keep the conversation brief. It’s recommended you:

The NIPVIP Program has been developed to increase patient access and affordability of vaccinations. From 1 January 2024, there are no out-of-pocket expenses for patients receiving NIP vaccines at participating pharmacies.44

Pharmacies that are registered for the NIPVIP will also receive payment of $19.32 per vaccination (current as at November 2024) for administering NIP vaccines to individuals aged 5 years and over in a pharmacy setting.45

Adolescent vaccination rates remain below optimal levels, often due to the COVID-related interruption to the school vaccination programs, increased vaccine hesitancy, and accessibility challenges. Pharmacists are uniquely positioned to educate and advocate for immunisation in adolescents who have missed their scheduled vaccinations and increase overall immunisation rates in this cohort by providing catch-up immunisations.

Case scenario continuedWhen filling a script for Kushal, you check the AIR and notice that he has missed his scheduled dose of dTpa vaccine. When he and his mother return to the pharmacy to collect his script, you ask if they’re aware of the missed dose. Both were vaguely aware of cancelled school vaccinations but didn’t think it was that important. You explain why vaccination is important and advise that Kushal could have a catch-up immunisation in the pharmacy if they choose. They both have some questions about the vaccine and potential adverse effects, which you answer. Kushal agrees to be vaccinated immediately, with his mother’s support. Both are grateful that you discussed the missed immunisation with them. |

[cpd_submit_answer_button]

Nerissa Bentley (she/her) is The Melbourne Health Writer – an award-winning professional health and medical writer who creates credible, evidence-based, AHPRA-compliant health copy for national organisations, global companies and Australian health practitioners.

Vaccine administration should be in accordance with relevant legislation, the Australian Immunisation Handbook, and state-based conditions specific to the vaccine.

[post_title] => How to increase vaccination rates in adolescents [post_excerpt] => Adolescent vaccination rates remain below optimal levels, often due to the COVID-related interruption to the school vaccination programs, increased vaccine hesitancy and accessibility challenges. Pharmacists are uniquely positioned to educate and advocate for immunisation in adolescents. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => how-to-increase-vaccination-rates-in-adolescents [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-03-18 12:47:24 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-18 01:47:24 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28721 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => How to increase vaccination rates in adolescents [title] => How to increase vaccination rates in adolescents [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/how-to-increase-vaccination-rates-in-adolescents/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 28924 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28930

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-17 12:23:04

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-17 01:23:04

[post_content] => PSA Lifetime Fellow Dr John McEwen’s evolution from pharmacy apprentice to international authority on pharmacovigilance reflects a career devoted to improving medicine safety.

Why did you decide to pursue pharmacy?

I finished secondary school aged 15 with little idea of a future career. I followed my father into pharmacy but was sensibly apprenticed to another pharmacist.

Tell us about your early career starting with your apprenticeship at the Victorian College of Pharmacy

I spent nearly half of each week at the College of Pharmacy and the remainder in the pharmacy, both in central Melbourne. At the time, that pharmacy sold cigarettes, Agarol (then containing oxyphenisatin) and was dispensing thalidomide. My almost daily task was to make one-gallon quantities of double- strength aspirin, phenacetin and caffeine mixture using a large mortar and pestle.

The College had excellent lecturers who motivated me to further study, leading to a Master of Science in neurophysiology, a period as a lecturer

in physiology and ultimately completing the MBBS.

How did your dual background in pharmacy and medicine shape your work in adverse drug reactions?

I was a resident at Royal Melbourne Hospital when the Department of Health advertised for the Medical Officer, Adverse Drug Reactions. My application was accepted!

I became Secretary to the Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee (ADRAC) where I was encouraged to find and publish medicine/reaction associations of likely clinical importance.1

Then, in 1979, I attended the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring. That led to global pharmacovigilance roles including as Chairperson, Advisory Group to the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC) (1985 –1987) and a member of the Executive Committee of the International Society of Pharmacovigilance (ISOP) 2006–2009.

What drove you to maintain your work with the TGA?

I enjoy exploring data relating to medicine efficacy and safety. In early retirement, I was contracted to write A History of Therapeutic Goods Regulation in Australia, published in 2007. It was a fascinating task, with many hours spent at the National Archives. That led to continuing part-time work for TGA, generally undertaking high-level reviews.

How did your senior roles at the TGA enable you to influence Australian medicine safety regulations?

In mid-1989, I developed the basic criteria for ‘less hazardous’ goods being entered in the ARTG, something not initially intended by the Commonwealth. As a consequence, the 1989 Therapeutic Goods legislation included provision for Listed Medicines, giving these Australian products a unique status in the domestic and export markets.

I contributed to the adoption in Australia of initial guidance for product sponsors concerning adverse reactions, including the Australian Pharmacovigilance Guideline (2002), provision for requiring Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs) and the Conjoint ADRAC-Medicines Australia guidelines for company-sponsored post-marketing surveillance (PMS) studies.).

What stands out as one of your proudest achievements or most meaningful contributions?

I arranged for the UMC Pharmacovigilance Training Course to be presented at TGA in 2002 and 2004. These were the first occasions the 2-week intensive course had been held outside Uppsala in Sweden. Many TGA colleagues generously contributed, giving Australia a very high status in global pharmacovigilance.

What advice would you give to pharmacists just starting their careers, especially those interested in pharmacovigilance or policy development?

Maintain the curiosity and analytical skills developed during undergraduate study as pharmacy offers many and varied opportunities, including in pharmacovigilance and policy development. Keep up to date throughout your career, as it will span many important developments and changes.

Reference

- Mackay K. Showing the blue card: reporting adverse reactions. Australian Prescriber 2005;28(6):140–2.

[post_title] => The science of safety

[post_excerpt] => All about PSA Lifetime Fellow Dr John McEwen’s evolution from pharmacy apprentice to international authority on pharmacovigilance.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => the-science-of-safety

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-03-17 12:23:04

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-17 01:23:04

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28930

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => The science of safety

[title] => The science of safety

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/the-science-of-safety/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28933

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28898

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-12 14:26:24

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-12 03:26:24

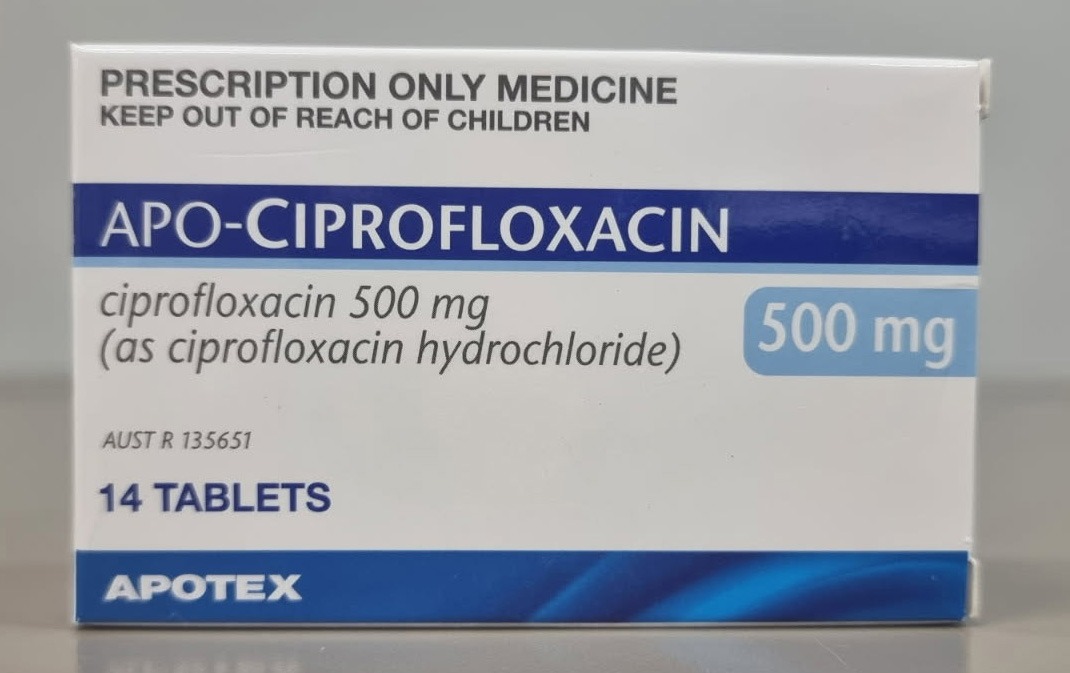

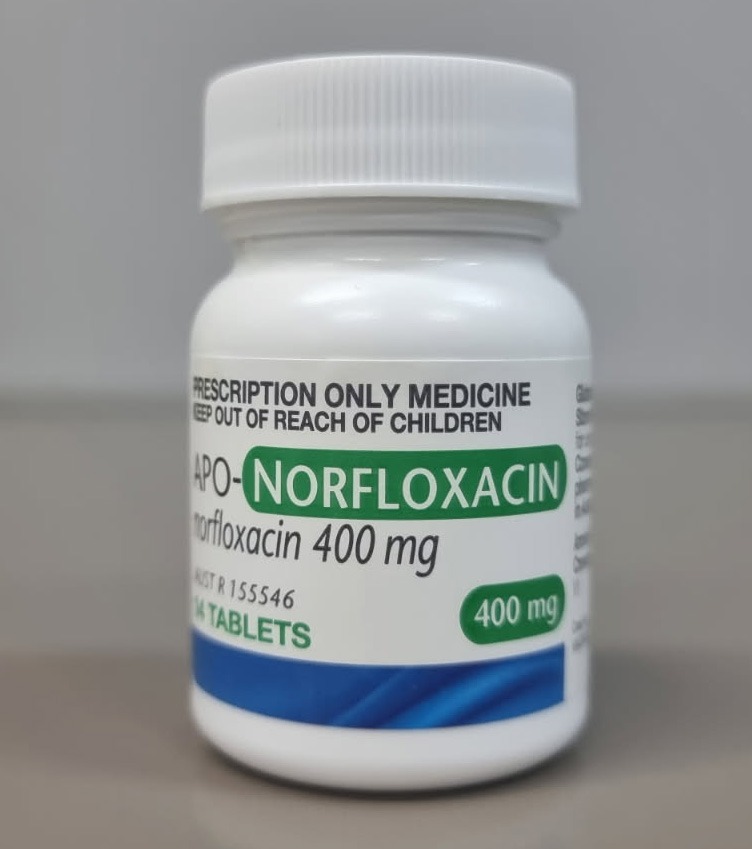

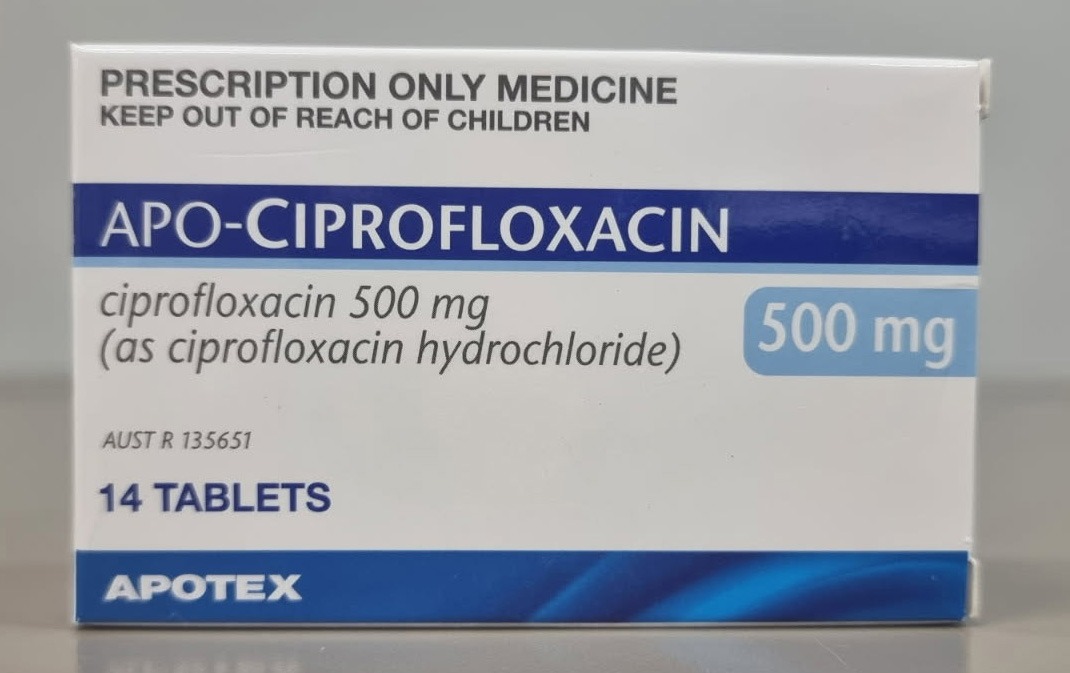

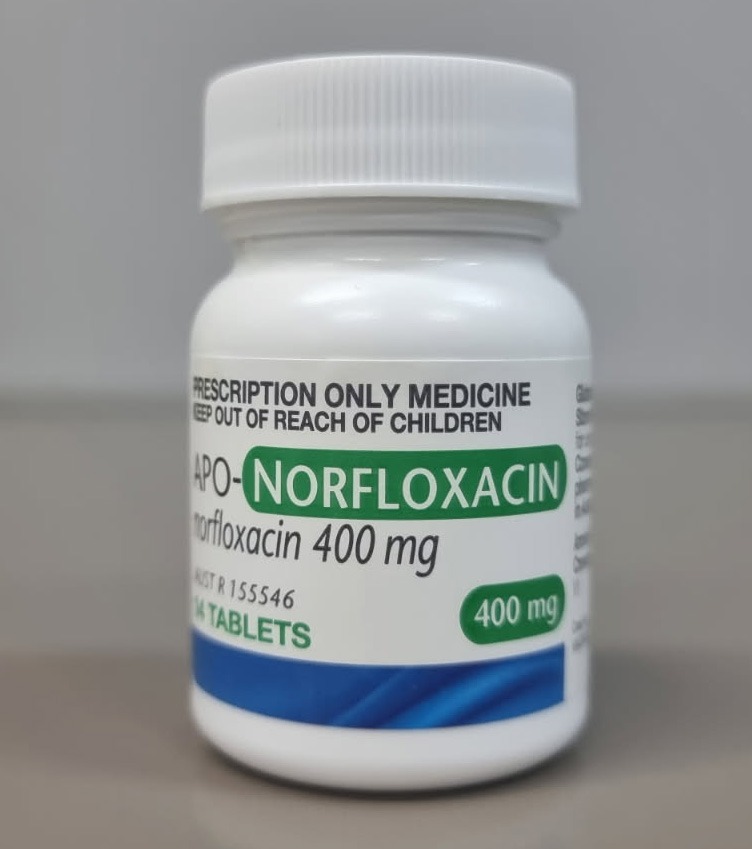

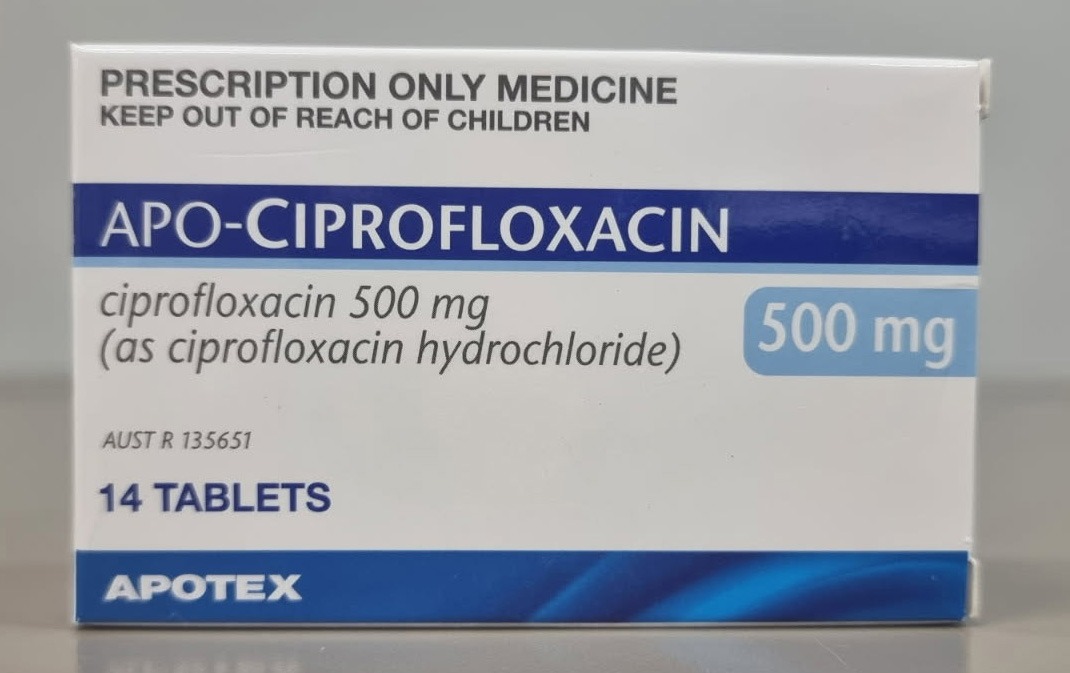

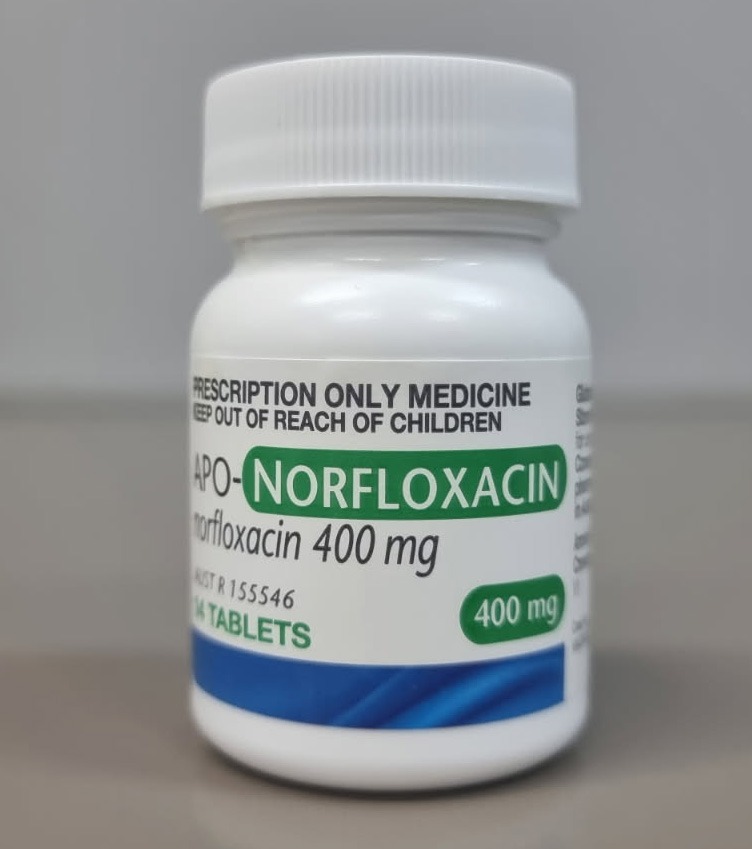

[post_content] => The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) issued an alert over the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used to treat infections such as urinary tract, respiratory and gastrointestinal infections.

What class of antibiotics prompted the alert?

Antimicrobials from the broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and moxifloxacin. This includes all oral and injectable forms of fluoroquinolones.

What are the documented adverse effects?

Central nervous system (CNS) and psychiatric events. Although rare, the complications are serious – and are potentially disabling and irreversible.

Adverse events include:

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28946

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-18 15:51:52

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-18 04:51:52

[post_content] => Around 4 million Australians (16% of the population) are living with back problems, with about 4 out of 5 people experiencing low back pain at some point in their lives.

Antidepressants are widely prescribed for low back pain and sciatica, with up to one in seven Australians with low back pain dispensed an antidepressant – most commonly the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline.

However, there is inconsistency across international clinical guidelines around their use for this indication, said Michael Ferraro, lead author of a review into Antidepressants for low back pain and spine‐related leg pain and Doctoral candidate at the Centre for Pain IMPACT, NeuRA, and the School of Health Sciences UNSW.

‘These medicines are very widely used clinically for sciatica, but there's barely any trial evidence to inform their use.'

Michael Ferraro

‘The general thought was that they might be useful in some patients,’ he said. ‘At an individual prescriber level, clinicians are more likely to prescribe an antidepressant as a second-line treatment, particularly where there might be issues with sleep or mood.’

The review looked at the effects of any antidepressant class – including serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants – on low back pain or spine-related leg pain (encompassing full nerve compression or referred pain into the leg).

While not all patients with low back pain have spine-related leg pain, those who do generally have worse pain and poorer long-term outcomes, Mr Ferraro said.

‘These medicines are very widely used clinically for sciatica, but there's barely any trial evidence to inform their use,’ he said.

One class of antidepressant is beneficial for low back pain

The main outcomes of the review were impacts on patient-reported pain intensity, adverse events and function 3 months after initiation of treatment – enough time for the medicine to have a therapeutic effect.

The review is an update of an older Cochrane review, published in 2008, with the newer review incorporating results from industry-sponsored trials that tested the SNRI duloxetine.

‘Those trials, which were run across multiple international sites and recruited large patient populations, focused on low back pain patients,’ Mr Ferraro said.

While the review found that only SNRIs were effective over placebo for low back pain intensity, this effect was marginal.

‘When we think about the average effect in the patients that received an SNRI versus those who received the placebo, there was only a difference of around five points out of 100,’ he said.

‘That's what we would consider small, and it might even be so small that it's not really a benefit that your average patient would appreciate.’

Another antidepressant helps for disability

While the evidence is uncertain on the impact of SSRIs for low back pain or spine-related pain, tricyclic antidepressants were found to have no effect on pain.

However, there was one unexpected benefit unearthed.

‘They had a small effect on disability,’ Mr Ferraro said. ‘Normally we would expect any effects on disability to be mediated via pain, so that was a little surprising.’

But to demonstrate clinical benefit, there should be evidence of effects on both pain and disability, he said.

Antidepressants probably do more harm than good in back pain

The review found a lack of evidence to determine whether use of SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants for low back pain and spine-related leg pain lead to adverse events.

However, there was an increased risk of experiencing any adverse event when using SNRIs.

‘While we didn’t look at adverse events formally, nausea, dry mouth and dizziness – the typical effects you'd have with an antidepressant – would be the ones that are most likely,’ Mr Ferraro said.

The next step for the research team is further investigation into the effects of SNRIs for spine-related leg pain.

‘Members of the author team are about to commence recruitment for a randomised trial of duloxetine for spine-related leg pain or sciatica, Mr Ferraro said. ‘That will be a critical study, as it will be large enough to fill the evidence gap we identified.’

Should antidepressants still be prescribed for this indication?

Cessation of antidepressants, including tapering too quickly, can come with withdrawal effects. So should patients be initiated on a treatment that could have little or no benefit, with the potential for adverse events down the line?

‘None of the trials we included in the review actually assessed adverse events after the treatment had ceased, so that's a really key research item that must be addressed in the future,’ Mr Ferraro said.

However, when prescribing or dispensing antidepressants for low back pain or sciatica, it’s important to point patients to evidence that the benefits, on average, are small and may not be appreciable.

‘[Pharmacists and GPs] should explain that there’s a risk of side effects – and extrapolating from other data sources – that some of those effects may be related to tapering an antidepressant if it's not effective.’

Pharmacists are also advised to check in with patients to see how they are coping with their pain.

‘The evidence we included found a benefit [of SNRIs] within 14 weeks, after a course of 2–3 months,’ he said. ‘So if there's no benefit within the first 3 months, it would be critical to have a discussion with the pharmacist and then the GP.’

What are the alternative treatment options?

In terms of pharmacological treatments, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard recommends non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for patients with low back pain who are at low risk of NSAID-related harm.

Along with antidepressants, anticonvulsants and benzodiazepines should generally be avoided – with the risks outweighing the benefits and little evidence for their effectiveness. Opioid analgesics should only be considered in carefully selected patients, using the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration.

Overall, medicines should be used judiciously, with physical and psychological interventions recommended first line to improve function.

[post_title] => Antidepressants show little to no benefit for low back pain and sciatica

[post_excerpt] => New major review finds that antidepressants used for back pain and sciatica can cause more harm than good.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => antidepressants-show-little-to-no-benefit-for-low-back-pain-and-sciatica

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-03-19 15:58:36

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-19 04:58:36

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28946

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Antidepressants show little to no benefit for low back pain and sciatica

[title] => Antidepressants show little to no benefit for low back pain and sciatica

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/antidepressants-show-little-to-no-benefit-for-low-back-pain-and-sciatica/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28951

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28935

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-17 12:46:47

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-17 01:46:47

[post_content] => Several women’s health medicines will be on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) after new PBAC recommendations.

The listings are in addition to the government’s $573 million women’s health funding announcement last month.

Australian Pharmacist takes a look at these new additions and the impact cheaper medicines will have on women across the nation.

Funding for first ever progesterone-only contraceptive pill

From 1 May, Slinda (drospirenone) – a first-of-its-kind progesterone-only oral contraceptive pill OCP – will be available under the PBS.

Around 80,000 women are paying privately for Slinda, which costs around $80 for 3 months’ supply.

Under the PBS, the medicine will only set women back $31.60 ($7.70 for concession card holders) for 4 months’ supply.

The move will widen birth control options for Australian women, particularly those who can have difficulty with oestrogen-based OCPs

Dr Terri Foran, Sexual Health Physician said Slinda is particularly suitable for women who:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28721

[post_author] => 8289

[post_date] => 2025-03-17 12:30:51

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-17 01:30:51

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_28925" align="alignright" width="292"] Sponsorship information

Sponsorship information

This educational activity was managed by PSA at the request of and with funding from GSK, Sanofi and CSL Seqirus.[/caption]

Kushal is a 16-year-old male who missed his dTpa vaccination in 2021 due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neither Kushal nor his mother fully understand the importance of vaccination or the diseases that this vaccine protects against.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Already read the CPD in the journal? Scroll to the bottom to SUBMIT ANSWERS.

Immunisation has reduced disease, disability and death from 26 infectious diseases. While Australia has a relatively high immunisation coverage by global standards, there are opportunities for improvement, particularly in the adolescent cohort. Reduced vaccination uptake in young people has consequences for their future health status as well as the health of the Australian population.

The World Health Organization considers immunisation to be the most effective medical intervention available to prevent death and reduce disease in our communities. Since routine immunisations of infants were introduced in Australia in the 1950s, death or disability from many once-common infectious diseases is now rare.

All vaccines currently used in Australia offer enough protection to prevent disease in most vaccinated individuals. However, high rates of immunisation are essential to protect the population from preventable diseases.

The NIP aims to increase national immunisation coverage to reduce vaccination-preventable diseases by administering immunisations at specific times throughout a person’s life. Free vaccines on the NIP are available to people who hold or are eligible to hold a Medicare card, including adolescents. Free catch-up vaccinations are also provided to people if they are missed for any reason. The National Immunisation Program Vaccinations in Pharmacy (NIPVIP) Program was introduced on 1 January 2024 and allows eligible patients to receive free NIP vaccines in a community pharmacy, which makes vaccination accessible and affordable. On 29 April 2024, the program expanded to include off-site vaccinations in residential aged care and disability homes, enabling pharmacies to claim payments for administering NIP vaccines in these settings.

The NIP Schedule outlines recommended vaccines and schedule points.

Adolescent vaccines protect against five key diseases.

Diphtheria

Diphtheria is a serious bacterial disease that primarily affects the nose and throat and can cause skin infections. It is spread through coughing and sneezing or direct contact with infected wounds or contaminated objects. Toxins released by the bacterium may cause a membrane to grow across the throat or windpipe, potentially leading to airway obstruction, making breathing difficult. If the membrane completely blocks the airways, the patient can suffocate and die. The disease can also cause systemic complications, including myocarditis and neuropathy. Due to high rates of vaccination, diphtheria is rare in Australia.

Tetanus

Tetanus is caused by Clostridium tetani bacteria found in soil and animal faeces, which can affect the nerves in the brain and spinal cord. Bacteria can enter the body through a wound (particularly dirty or deep wounds) or a bite. The infection can lead to severe muscle spasms, particularly in the neck and jaw (lockjaw). Around 10% of people who get tetanus will die, with babies and older people having the highest risk of death.

Tetanus is now rare in Australia due to vaccination rates, although it mostly occurs in older adults who are not adequately vaccinated.

Pertussis

Pertussis (whooping cough) is a highly contagious bacterial respiratory infection caused by Bordetella pertussis, spread through coughing or sneezing. It can lead to severe coughing fits, difficulty breathing, pneumonia, brain damage and sometimes death. Despite the availability of vaccines for more than 50 years, pertussis remains a challenging disease to control as immunity wanes over time. Pertussis is especially serious for babies, but it can affect people of any age. It is always circulating in the community and epidemics occur in Australia every 3–4 years. There is currently a pertussis epidemic in Australia.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

HPV is a group of viruses spread through sexual contact. HPV is responsible for almost all cases of genital warts and cervical cancer. It can also lead to cancer of the anus, vagina, vulva and penis. Since the introduction of HPV vaccination in 2007, there has been a steady decline in high-grade cervical abnormalities in younger women. Research shows that widespread use of the HPV vaccine dramatically reduces the number of women who will develop cervical cancer. The Australian target of vaccinating 90% of all eligible people against HPV is one of three pillars in the Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative to achieve cervical cancer elimination by 2030.

Men who have sex with men (MSM) may be disproportionally at risk of HPV infection and associated diseases. This cohort may be up to 20 times more likely to develop anal cancer and 2–3 times more likely to develop genital warts compared with heterosexual males.

Males born before 1999 may not previously have been offered the HPV vaccine and may derive little herd benefit from the vaccination of females.

Prevention of HPV infection is important as there is currently no routine screening program for early detection of anal cancer.

Meningococcal ACWY

Meningococcal disease is a serious infection caused by Neisseria meningitidis, commonly referred to as meningococcus. Serogroups A, B, C, W and Y most commonly cause the disease and are transmitted in secretions from the back of the nose and throat, generally through close and prolonged contact. Meningococcal disease can develop quickly and is a medical emergency as it can be fatal within hours without treatment. Since the introduction of the meningococcal ACWY vaccination, the incidence of meningococcal disease has reduced, and the overall rate of invasive meningococcal disease fell to 0.3 per 100,000 in 2021.

The NIP provides a series of immunisations for adolescents, which are primarily delivered through school-based vaccination programs and other health services, including pharmacies.8

Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (dTpa)

Adolescents aged 11–13 years (Year 7) should receive a booster dose of combined diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (dTpa) reduced-antigen vaccine. A booster dose is required as pertussis immunity wanes after the childhood primary series, the last vaccine being administered at 4 years., Fully vaccinated adolescents will be protected from these diseases for many years, although they may need a tetanus or pertussis booster in the future. Adolescents should receive one dose of pertussis-containing vaccine, regardless of the number of previous doses they received before 10 years of age.26

Two dTpa vaccines are available: Boostrix and Adacel. Both are in 0.5 mL pre-filled syringes and are administered as an intramuscular injection (IMI) into the deltoid muscle of the upper arm.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

Adolescents are recommended to receive the 9vHPV (9-valent HPV) vaccine starting from age 9. However, the optimal age is 12–13 years (Year 7).30

Gardasil 9 is the adolescent HPV vaccine available on the NIP from age 12–13 years with a recommended single-dose schedule for those who are not immunocompromised. Free catch-up vaccinations are offered up to and including 25 years of age.30

Meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY)

It is recommended adolescents aged 14–16 years (Year 10) receive one dose of meningococcal ACWY vaccine. MenQuadfi is the vaccine available on the NIP for adolescents aged 14–16 years.31 Meningococcal ACWY vaccine comes in a pre-measured 0.5 mL dose and is given as an IMI, usually in the deltoid muscle.32 Catch-up immunisations for meningococcal ACWY are free for eligible people under 20 years old under the NIP.

Patients who are not eligible under the NIP can access them privately, by paying a fee. If they have private health insurance, they may be able to claim a rebate, depending on their policy and coverage.

Immunisation uptake in adolescents declined in 2023 when compared with 2022.2

In 2023, 85.5% of adolescents turning 15 years received the dTpa adolescent booster dose compared to 86.9% in 2022.

In 2023, 84.2% of Australian girls had received at least one dose of HPV vaccine by 15 years of age, down from 85.3% in 2021; 81.8% of boys had received at least one dose, down from 83.1%.

Coverage of an adolescent dose of meningococcal ACWY vaccine in adolescents turning 17 years in 2023 was 72.8%, compared with 75.9% in 2022.

Coverage rates for all types of vaccines in First Nations adolescents were lower than rates for non-First Nations adolescents, while adolescents in lower socioeconomic areas had lower immunisation rates than those from higher socioeconomic areas. These differences may be a result of a lack of accessibility due to location, fewer financial resources, or lower rates of education and health literacy.

The decrease in immunisation uptake in Australian adolescents is due to several factors, one of which is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lengthy school closures in some jurisdictions during 2020 and 2021 that disrupted school-based immunisation programs during that time have been well documented.2

In addition, COVID-19 has led to a change in attitude towards immunisation. People, particularly parents, are asking more questions, and increasing levels of concern about vaccinations are evident.33 Furthermore, lack of parental support and consent for vaccination means that vaccine uptake in young people (aged 12–17 years) continues to be a challenge.3

Lagging vaccination rates are also attributable to accessibility factors, including distance to a vaccination provider, available appointments, and costs involved in vaccination, such as doctor visits, and the need to take time off work or put other children into care to attend doctor appointments.2

Catch-up vaccinations aim to provide the best protection against vaccine-preventable diseases as quickly as possible by completing a person’s recommended vaccination schedule. Catch-up vaccinations should be offered to all adolescents who have not received the vaccines scheduled in the NIP and should be administered according to age-appropriate guidelines in the Australian Immunisation Handbook. Free catch-up vaccines are available for missed vaccines under the NIP until the age of 20, except for the HPV vaccine which is available up to and including age 25.8 Pharmacists can administer these vaccines.

Research shows pharmacists are uniquely positioned to increase vaccination coverage rates among adolescents and other eligible populations.34 Pharmacists can identify individuals who have missed vaccinations by checking the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) and ensuring they are offered catch-up immunisation. They can advocate for and encourage vaccination in adolescents, and appropriately trained pharmacists can administer immunisations.35

Community pharmacists are among the most trusted and respected health professionals across Australia.36 Pharmacists have been administering vaccinations since 2014, and it is widely accepted across all states and territories that vaccination is within the scope of practice for appropriately trained pharmacists. Through proactive discussions within the pharmacy environment, pharmacists are in a prime position to boost adolescent immunisation rates.

Pharmacists should ascertain vaccination status in adolescents to facilitate conversations around immunisation.

Ascertaining vaccination status

Check the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR)

Pharmacists should routinely check prior immunisation history on the AIR when dispensing prescriptions. If the adolescent is overdue for their vaccination, this can be mentioned when giving them their medication and a discussion initiated. Running AIR reports in advance (e.g. AIR10A Due/Overdue Report) for regular patients or certain cohorts may provide greater efficiencies. This could be particularly helpful if pharmacists wish to run vaccination clinics to coincide with various health awareness campaigns, (e.g. World Immunisation Week or National Meningococcal Week).

Vaccination status on the AIR must be checked before administering any vaccine, and any vaccines administered must be recorded on the AIR.35

Ask about immunisation history

During general conversations, pharmacists can ask about immunisation history and explain that the pharmacy offers catch-up vaccinations for those who need them. Pharmacists should also offer to check the AIR if the patient is unsure about their immunisation status.

Initiate conversation

Pharmacists who have identified adolescents behind in their scheduled immunisations should initiate a conversation about a catch-up immunisation. The goals of these discussions will depend upon the patient’s attitude towards vaccination.37

Talking to patients who are ready to vaccinate

The goal of the consultation is to prevent hesitancy and support timely vaccination. People who are ready to vaccinate tend to trust medical advice. However, as many as half will have questions about vaccination.38 Ensure patients feel confident to ask questions without judgement. Some in this cohort say they are concerned providers will think they are ‘antivaxxers’ if they ask questions about vaccination.39 The following actions are recommended40:

Talking to patients who have questions

Talking to patients who have questions

The goal of the consultation is to vaccinate and increase vaccine confidence. Some people report feeling they are not sufficiently informed to agree to vaccination confidently, while some need permission to express and explore their concerns.38 It is recommended you:

The goal of the consultation is to maintain trust and engagement and keep the conversation brief. It’s recommended you:

The NIPVIP Program has been developed to increase patient access and affordability of vaccinations. From 1 January 2024, there are no out-of-pocket expenses for patients receiving NIP vaccines at participating pharmacies.44

Pharmacies that are registered for the NIPVIP will also receive payment of $19.32 per vaccination (current as at November 2024) for administering NIP vaccines to individuals aged 5 years and over in a pharmacy setting.45

Adolescent vaccination rates remain below optimal levels, often due to the COVID-related interruption to the school vaccination programs, increased vaccine hesitancy, and accessibility challenges. Pharmacists are uniquely positioned to educate and advocate for immunisation in adolescents who have missed their scheduled vaccinations and increase overall immunisation rates in this cohort by providing catch-up immunisations.

Case scenario continuedWhen filling a script for Kushal, you check the AIR and notice that he has missed his scheduled dose of dTpa vaccine. When he and his mother return to the pharmacy to collect his script, you ask if they’re aware of the missed dose. Both were vaguely aware of cancelled school vaccinations but didn’t think it was that important. You explain why vaccination is important and advise that Kushal could have a catch-up immunisation in the pharmacy if they choose. They both have some questions about the vaccine and potential adverse effects, which you answer. Kushal agrees to be vaccinated immediately, with his mother’s support. Both are grateful that you discussed the missed immunisation with them. |

[cpd_submit_answer_button]

Nerissa Bentley (she/her) is The Melbourne Health Writer – an award-winning professional health and medical writer who creates credible, evidence-based, AHPRA-compliant health copy for national organisations, global companies and Australian health practitioners.

Vaccine administration should be in accordance with relevant legislation, the Australian Immunisation Handbook, and state-based conditions specific to the vaccine.

[post_title] => How to increase vaccination rates in adolescents [post_excerpt] => Adolescent vaccination rates remain below optimal levels, often due to the COVID-related interruption to the school vaccination programs, increased vaccine hesitancy and accessibility challenges. Pharmacists are uniquely positioned to educate and advocate for immunisation in adolescents. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => how-to-increase-vaccination-rates-in-adolescents [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-03-18 12:47:24 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-18 01:47:24 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28721 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => How to increase vaccination rates in adolescents [title] => How to increase vaccination rates in adolescents [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/how-to-increase-vaccination-rates-in-adolescents/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 28924 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28930

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-17 12:23:04

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-17 01:23:04

[post_content] => PSA Lifetime Fellow Dr John McEwen’s evolution from pharmacy apprentice to international authority on pharmacovigilance reflects a career devoted to improving medicine safety.

Why did you decide to pursue pharmacy?

I finished secondary school aged 15 with little idea of a future career. I followed my father into pharmacy but was sensibly apprenticed to another pharmacist.

Tell us about your early career starting with your apprenticeship at the Victorian College of Pharmacy

I spent nearly half of each week at the College of Pharmacy and the remainder in the pharmacy, both in central Melbourne. At the time, that pharmacy sold cigarettes, Agarol (then containing oxyphenisatin) and was dispensing thalidomide. My almost daily task was to make one-gallon quantities of double- strength aspirin, phenacetin and caffeine mixture using a large mortar and pestle.

The College had excellent lecturers who motivated me to further study, leading to a Master of Science in neurophysiology, a period as a lecturer

in physiology and ultimately completing the MBBS.

How did your dual background in pharmacy and medicine shape your work in adverse drug reactions?

I was a resident at Royal Melbourne Hospital when the Department of Health advertised for the Medical Officer, Adverse Drug Reactions. My application was accepted!

I became Secretary to the Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee (ADRAC) where I was encouraged to find and publish medicine/reaction associations of likely clinical importance.1

Then, in 1979, I attended the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring. That led to global pharmacovigilance roles including as Chairperson, Advisory Group to the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC) (1985 –1987) and a member of the Executive Committee of the International Society of Pharmacovigilance (ISOP) 2006–2009.

What drove you to maintain your work with the TGA?

I enjoy exploring data relating to medicine efficacy and safety. In early retirement, I was contracted to write A History of Therapeutic Goods Regulation in Australia, published in 2007. It was a fascinating task, with many hours spent at the National Archives. That led to continuing part-time work for TGA, generally undertaking high-level reviews.

How did your senior roles at the TGA enable you to influence Australian medicine safety regulations?

In mid-1989, I developed the basic criteria for ‘less hazardous’ goods being entered in the ARTG, something not initially intended by the Commonwealth. As a consequence, the 1989 Therapeutic Goods legislation included provision for Listed Medicines, giving these Australian products a unique status in the domestic and export markets.

I contributed to the adoption in Australia of initial guidance for product sponsors concerning adverse reactions, including the Australian Pharmacovigilance Guideline (2002), provision for requiring Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs) and the Conjoint ADRAC-Medicines Australia guidelines for company-sponsored post-marketing surveillance (PMS) studies.).

What stands out as one of your proudest achievements or most meaningful contributions?

I arranged for the UMC Pharmacovigilance Training Course to be presented at TGA in 2002 and 2004. These were the first occasions the 2-week intensive course had been held outside Uppsala in Sweden. Many TGA colleagues generously contributed, giving Australia a very high status in global pharmacovigilance.

What advice would you give to pharmacists just starting their careers, especially those interested in pharmacovigilance or policy development?

Maintain the curiosity and analytical skills developed during undergraduate study as pharmacy offers many and varied opportunities, including in pharmacovigilance and policy development. Keep up to date throughout your career, as it will span many important developments and changes.

Reference

- Mackay K. Showing the blue card: reporting adverse reactions. Australian Prescriber 2005;28(6):140–2.

[post_title] => The science of safety

[post_excerpt] => All about PSA Lifetime Fellow Dr John McEwen’s evolution from pharmacy apprentice to international authority on pharmacovigilance.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => the-science-of-safety

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-03-17 12:23:04

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-17 01:23:04

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28930

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => The science of safety

[title] => The science of safety

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/the-science-of-safety/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28933

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28898

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-12 14:26:24

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-12 03:26:24

[post_content] => The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) issued an alert over the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used to treat infections such as urinary tract, respiratory and gastrointestinal infections.

What class of antibiotics prompted the alert?

Antimicrobials from the broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and moxifloxacin. This includes all oral and injectable forms of fluoroquinolones.

What are the documented adverse effects?

Central nervous system (CNS) and psychiatric events. Although rare, the complications are serious – and are potentially disabling and irreversible.

Adverse events include:

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28946

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-18 15:51:52

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-18 04:51:52

[post_content] => Around 4 million Australians (16% of the population) are living with back problems, with about 4 out of 5 people experiencing low back pain at some point in their lives.

Antidepressants are widely prescribed for low back pain and sciatica, with up to one in seven Australians with low back pain dispensed an antidepressant – most commonly the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline.

However, there is inconsistency across international clinical guidelines around their use for this indication, said Michael Ferraro, lead author of a review into Antidepressants for low back pain and spine‐related leg pain and Doctoral candidate at the Centre for Pain IMPACT, NeuRA, and the School of Health Sciences UNSW.

‘These medicines are very widely used clinically for sciatica, but there's barely any trial evidence to inform their use.'

Michael Ferraro

‘The general thought was that they might be useful in some patients,’ he said. ‘At an individual prescriber level, clinicians are more likely to prescribe an antidepressant as a second-line treatment, particularly where there might be issues with sleep or mood.’

The review looked at the effects of any antidepressant class – including serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants – on low back pain or spine-related leg pain (encompassing full nerve compression or referred pain into the leg).

While not all patients with low back pain have spine-related leg pain, those who do generally have worse pain and poorer long-term outcomes, Mr Ferraro said.

‘These medicines are very widely used clinically for sciatica, but there's barely any trial evidence to inform their use,’ he said.

One class of antidepressant is beneficial for low back pain

The main outcomes of the review were impacts on patient-reported pain intensity, adverse events and function 3 months after initiation of treatment – enough time for the medicine to have a therapeutic effect.

The review is an update of an older Cochrane review, published in 2008, with the newer review incorporating results from industry-sponsored trials that tested the SNRI duloxetine.

‘Those trials, which were run across multiple international sites and recruited large patient populations, focused on low back pain patients,’ Mr Ferraro said.

While the review found that only SNRIs were effective over placebo for low back pain intensity, this effect was marginal.

‘When we think about the average effect in the patients that received an SNRI versus those who received the placebo, there was only a difference of around five points out of 100,’ he said.

‘That's what we would consider small, and it might even be so small that it's not really a benefit that your average patient would appreciate.’

Another antidepressant helps for disability

While the evidence is uncertain on the impact of SSRIs for low back pain or spine-related pain, tricyclic antidepressants were found to have no effect on pain.

However, there was one unexpected benefit unearthed.

‘They had a small effect on disability,’ Mr Ferraro said. ‘Normally we would expect any effects on disability to be mediated via pain, so that was a little surprising.’

But to demonstrate clinical benefit, there should be evidence of effects on both pain and disability, he said.

Antidepressants probably do more harm than good in back pain

The review found a lack of evidence to determine whether use of SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants for low back pain and spine-related leg pain lead to adverse events.

However, there was an increased risk of experiencing any adverse event when using SNRIs.

‘While we didn’t look at adverse events formally, nausea, dry mouth and dizziness – the typical effects you'd have with an antidepressant – would be the ones that are most likely,’ Mr Ferraro said.

The next step for the research team is further investigation into the effects of SNRIs for spine-related leg pain.

‘Members of the author team are about to commence recruitment for a randomised trial of duloxetine for spine-related leg pain or sciatica, Mr Ferraro said. ‘That will be a critical study, as it will be large enough to fill the evidence gap we identified.’

Should antidepressants still be prescribed for this indication?

Cessation of antidepressants, including tapering too quickly, can come with withdrawal effects. So should patients be initiated on a treatment that could have little or no benefit, with the potential for adverse events down the line?

‘None of the trials we included in the review actually assessed adverse events after the treatment had ceased, so that's a really key research item that must be addressed in the future,’ Mr Ferraro said.

However, when prescribing or dispensing antidepressants for low back pain or sciatica, it’s important to point patients to evidence that the benefits, on average, are small and may not be appreciable.

‘[Pharmacists and GPs] should explain that there’s a risk of side effects – and extrapolating from other data sources – that some of those effects may be related to tapering an antidepressant if it's not effective.’

Pharmacists are also advised to check in with patients to see how they are coping with their pain.

‘The evidence we included found a benefit [of SNRIs] within 14 weeks, after a course of 2–3 months,’ he said. ‘So if there's no benefit within the first 3 months, it would be critical to have a discussion with the pharmacist and then the GP.’

What are the alternative treatment options?

In terms of pharmacological treatments, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care’s Low Back Pain Clinical Care Standard recommends non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for patients with low back pain who are at low risk of NSAID-related harm.

Along with antidepressants, anticonvulsants and benzodiazepines should generally be avoided – with the risks outweighing the benefits and little evidence for their effectiveness. Opioid analgesics should only be considered in carefully selected patients, using the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration.

Overall, medicines should be used judiciously, with physical and psychological interventions recommended first line to improve function.

[post_title] => Antidepressants show little to no benefit for low back pain and sciatica

[post_excerpt] => New major review finds that antidepressants used for back pain and sciatica can cause more harm than good.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => antidepressants-show-little-to-no-benefit-for-low-back-pain-and-sciatica

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-03-19 15:58:36

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-19 04:58:36

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28946

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Antidepressants show little to no benefit for low back pain and sciatica

[title] => Antidepressants show little to no benefit for low back pain and sciatica

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/antidepressants-show-little-to-no-benefit-for-low-back-pain-and-sciatica/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28951

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28935

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-17 12:46:47

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-17 01:46:47

[post_content] => Several women’s health medicines will be on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) after new PBAC recommendations.

The listings are in addition to the government’s $573 million women’s health funding announcement last month.

Australian Pharmacist takes a look at these new additions and the impact cheaper medicines will have on women across the nation.

Funding for first ever progesterone-only contraceptive pill

From 1 May, Slinda (drospirenone) – a first-of-its-kind progesterone-only oral contraceptive pill OCP – will be available under the PBS.

Around 80,000 women are paying privately for Slinda, which costs around $80 for 3 months’ supply.

Under the PBS, the medicine will only set women back $31.60 ($7.70 for concession card holders) for 4 months’ supply.

The move will widen birth control options for Australian women, particularly those who can have difficulty with oestrogen-based OCPs

Dr Terri Foran, Sexual Health Physician said Slinda is particularly suitable for women who:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28721

[post_author] => 8289

[post_date] => 2025-03-17 12:30:51