Dispensing of psychotropic medicines to Australian children and adolescents aged 18 and younger doubled from 2013 to 2021, new research by Monash University has found.

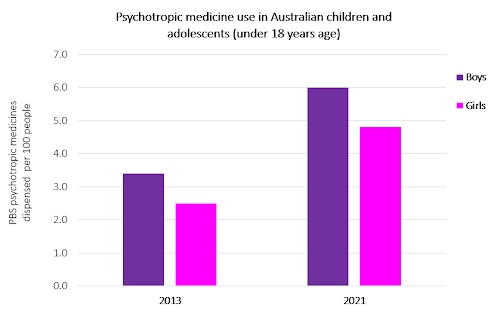

Analysis of a 10% random sample of Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme dispensing data found dispensing of antidepressant, anxiolytic, antipsychotic, psychostimulant, and sedative medicines to children and adolescents was 3.4 per 100 boys and 2.5 per 100 girls in 2013, and 6.0 per 100 boys and 4.8 per 100 girls in 2021.

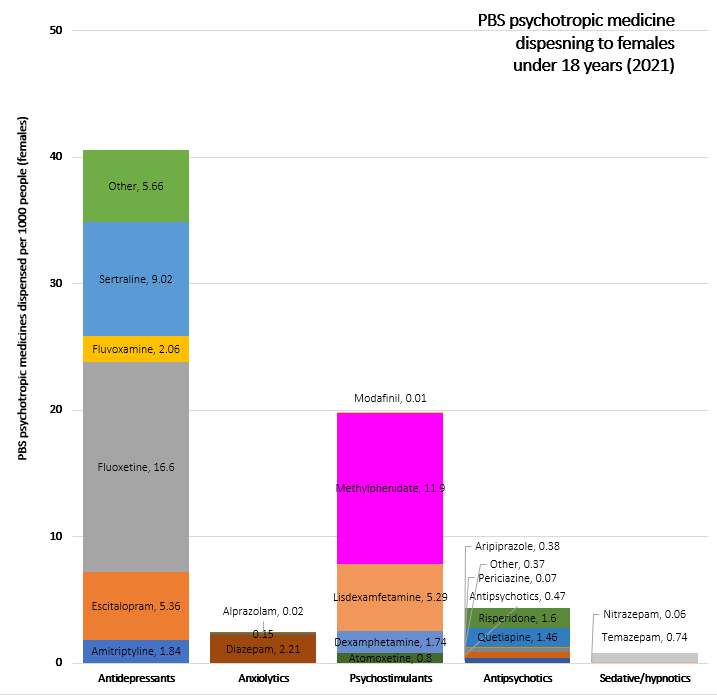

Overall, the increases in psychotropic dispensing were greatest among girls aged 13–18 years.

‘The largest increase in dispensing of psychotropic medicines during this time period appears to relate to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic,’ said Associate Professor Luke Grzeskowiak, the study’s senior author.

Psychotropic polypharmacy for children and adolescents was also twice as high in 2021 than in 2013, with greater increases seen during the pandemic, particularly among girls in this age cohort.

‘The impact of isolation, lockdown and lack of availability of in-person health services may have also contributed to the increases reported in 2020 and 2021,’ said Dr Sarira El-Den MPS, pharmacist and Senior Lecturer at The University of Sydney School of Pharmacy, and Mental Health First Aid Master Instructor.

‘The findings are similar to what other studies from Australia and around the world have reported, meaning this is potentially a global issue and a coordinated response [where] contribution of all members of the healthcare team may be needed.’

‘The findings are similar to what other studies from Australia and around the world have reported, meaning this is potentially a global issue and a coordinated response [where] contribution of all members of the healthcare team may be needed.’

The role of pharmacists

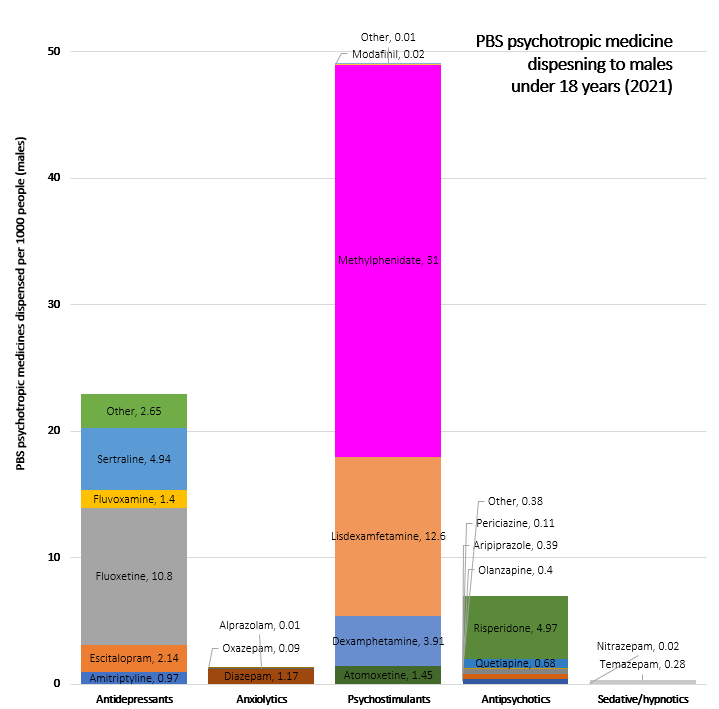

Psychotropic medicines can be prescribed for children and adolescents with mental disorders, including schizophrenia, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, depression and anxiety.

Due to the ethical challenges of conducting research on children, findings of studies conducted on adults are sometimes used to guide decision-making for children and young people, said Dr El-Den.

Guidelines providing recommendations around the use of psychotropic medicines for children and young people should be referred to while prescribing or dispensing, including the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists’ Guidance for psychotropic medication use in children and adolescents.

When providing clinical support to children and young people, pharmacists need to:

- counsel on medicine use

- provide information regarding the potential benefits and adverse effects associated with the medicines

- contribute to risk versus benefit assessments and decision-making as members of the healthcare team

- refer to other healthcare providers when needed

- promote awareness of and facilitate access to resources and non-pharmacological treatment options.

Adverse effects, monitoring and treatment plans

Although psychotropic medicines can benefit children and adolescents with mental disorders, their efficacy and safety in young people remains the subject of debate, said A/Prof Grzeskowiak.

‘The fact that rates were in part driven by increased longer-term use of psychotropics is concerning, particularly given evidence of benefits and harms in young people is usually limited to short-term use,’ he said.

On the whole, the adverse effects of psychotropic medicines in young people are similar to those in adults, said A/Prof Grzeskowiak. These include:

- extrapyramidal adverse effects and weight gain with antipsychotics

- anorexia and insomnia with psychostimulants.

‘For antidepressants, there is evidence of a slight increase in suicidal ideation, so it’s important there is appropriate monitoring is in place, particularly early in treatment,’ he said.

Psychotropic medicines should be used as part of a comprehensive clinical management plan that includes use of non-pharmacological strategies to identify and address factors that may contribute to the underlying disorder, said A/Prof Grzeskowiak.

‘There should be clear plans in place for ongoing monitoring and review, particularly for antidepressants, where evidence from clinical trials is largely following short-term use,’ he said.

Evidence-based non-pharmacological options should be considered when treating mental illnesses in children and young people, said Dr El-Den.

‘As pharmacists we can enquire about whether these options, such as psychological therapies, have been considered and if they have been used, how the child or young person has responded to them,’ she said.

Online options for help-seeking can also improve awareness of non-pharmacological treatments along with local mental health services, including:

Addressing polypharmacy

Increasing rates of psychotropic polypharmacy also raise several concerns, said A/Prof Grzeskowiak.

‘The potential for drug-drug interactions and increased risk of adverse events could lead to poor treatment adherence,’ he said.

When psychotropic polypharmacy is detected in young people, a referral for a Home Medicines Review (HMR) could be beneficial, said Dr El-Den.

‘[HMRs] provide an opportunity for pharmacists to sit down with the child or young person and their family members or caregivers, and have a detailed discussion about their medicines and health,’ she said.

‘Some research shows young people would like more information about their medications, so HMRs may be one way pharmacists can support these needs.’

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more