With better treatments than ever, why don’t patients with respiratory conditions show better outcomes as well?

Over the past 2 decades, understanding of the pathophysiology and treatment of chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and allergic rhinitis has advanced.

There are now better inhalers and newer, targeted drugs. But despite these technological advances, we are failing to see significant improvements in the day-to-day management of chronic respiratory conditions and many patients continue to live with a high burden of disease. Why? Because similar advancements have not been achieved in improved asthma literacy or helping people with asthma change poor asthma management behaviours, says Professor Bandana Saini, a University of Sydney respiratory specialist at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research.

Outside hospitals, treatments have developed that are very similar for asthma and COPD, says the Chair of the inaugural Respiratory Pharmacy Taskforce, Professor Sinthia Bosnic-Anticevich MPS – who will speak at PSA22.

‘But they are used in a different order or slightly different doses or in different combinations. And at the same time, when we look at the management, or how well people are doing with the burden of those diseases, it really hasn’t improved in the last 20 years.’

Long-acting βeta agonists when introduced were a game changer, providing 12-hour bronchodilation. However, the reduction in burden of disease has not matched what had been hoped.

‘Not much has really changed – we’ve been working with the same parameters for a long time,’ says Prof Bosnic-Anticevich.

Biologic agents, developed to target specific inflammatory mediators, ’tend to be reserved more for the severe end of the spectrum’, she says.

As a result of the biologics, ‘we’re starting to question whether we are understanding and approaching the treatment of these diseases in the right way.’

The key problem remains managing suboptimal practices in chronic respiratory conditions, and how pharmacists can personalise their approach.

‘People still have a poor perception of their symptoms; they are non-adherent to their medications; and they still have poor inhaler technique,’ Prof Bosnic-Anticevich points out. ‘People are using probably more short-acting βeta agonist relievers than they should. They’re using oral corticosteroids more than we would recommend.

‘We still have people who otherwise would have mild disease, sometimes getting severe exacerbations.’

Pharmacists and SABAs

Pharmacists and SABAs

Advanced practice pharmacist Debbie Rigby FPS agrees that pharmacists can be a massive resource in the management of respiratory diseases, with asthma an important example.

‘Asthma deaths remain high, especially for women aged over 75 years,’ she says.

‘In 2020, there were 417 asthma-related deaths recorded in Australia. Australia has one of the highest prevalence rates in the world, but pharmacists can do more to reduce these asthma-related deaths and improve control of asthma.’

In recent years there has been a fundamental shift in the management of asthma, prompted by concerns about the risks and consequences of the long-standing approach of starting asthma treatment with short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs) alone, says Ms Rigby.

Over-reliance on SABAs and under-use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are both associated with an increase in mortality. Regular or frequent use of SABAs has also been shown to increase the risk of near-fatal and fatal asthma exacerbations.

Most adults and adolescents should be commenced on either regular daily maintenance low-dose ICS or as-needed low-dose budesonide–formoterol.

‘Pharmacists need to be more proactive in helping patients understand the goals of asthma treatment, which is to control current symptoms and reduce the risk of an exacerbation,’ Ms Rigby says.

‘Patients know they get quick relief from SABAs, but need to understand they do nothing for the underlying inflammation in the airways.

‘Only ICS will help with the inflammation and mucous production and need to be taken regularly.’

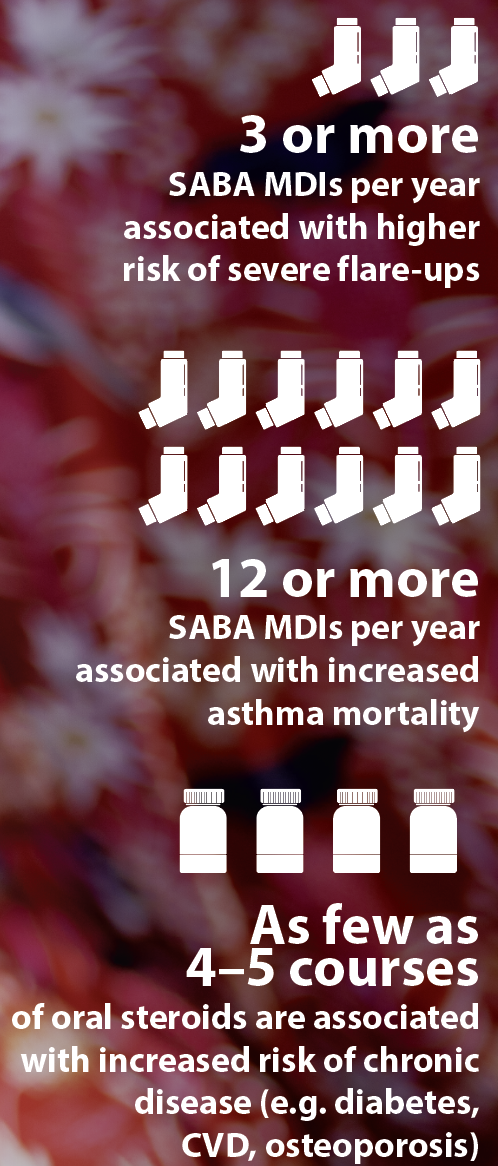

The use of three or more canisters of SABA per year is associated with a greater risk of severe exacerbations. Use of 12 or more inhalers in a year is associated with an increased risk of asthma-related death.

Box 1 – Chronic respiratory conditions

Australia’s disease burden includes: |

| Asthma –

5th largest cause of non-fatal disease burden in Australia1 $770 million cost to health system in 2015–162 19% of disease expenditure on respiratory conditions2 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) –

5th leading cause of death3,4 1st (leading) respiratory cause of avoidable hospital admissions5 7.5% of Australians over 40 are believed to have COPD with smoking the most significant cause6 20% of people with COPD also have asthma overlap7 |

| Bronchiectasis –

chronic condition, with abnormal, irreversible dilatation of the bronchi.8 387 deaths in 2018; initial symptoms (cough, sputum, dyspnoea) overlap with asthma and COPD, but there is a different outcome.9 |

| Allergic rhinitis –

4.6 million Australians affected in 2017–18 (1 in 5 or 19%)10 |

References: AIHW1–5, Toelle et al6, Lung Foundation Australia7, Bronchiectasis Toolbox8, AIHW9,10

Patient misconceptions

‘A common misconception’ among chronic respiratory patients is that regular inhaler use will cause ‘dependence’, says Katherine Borg, a senior clinical pharmacist at Concord Repatriation General Hospital.

‘As a result, bronchodilator therapy is used intermittently rather than as regular maintenance therapy. It is important that we ensure patients understand that optimum disease control can only be attained by consistent adherence with their inhaler regimen.

‘As pharmacists we must ensure patient understanding that features of chronic respiratory conditions are persistent, even when symptoms are absent, or when it appears that lung function is normal.’

Ms Borg stresses that education and training on correct inhaler use are of paramount importance. ‘However, our role extends beyond this as it is also crucial that we reinforce positive perceptions toward inhaler management, and towards disease control.’

Ms Borg’s work in COPD focuses on the relationship between dry powder inhalers and peak inspiratory flow (PIF), a unique physiological parameter involving a patient’s ability to inspirate.

‘It is well understood by pharmacists that using an inhaler correctly requires the completion of a series of steps associated with the correct use of that specific inhaler.’

However, the assessment of a patient’s ability to inhale through a particular device prior to it being prescribed is untested.

What is ‘rarely evaluated’, Ms Borg points out, is a ‘patient’s ability to inspire adequately or appropriately through an inhaler device’ which can compromise medication efficacy.

‘There is still much to learn about PIF in practice, and its impact on day-to-day medication management,’ she says. ‘This is an up-and-coming topic of interest both overseas and in Australia.’ (See Improving respiratory outcomes, guidelines and reducing the carbon footprint in the PSA22 program at: https://bit.ly/3KbKgF3)

Another fundamental change in respiratory care, says Ms Rigby, is the use of as-needed low-dose budesonide–formoterol in patients with mild asthma. This can be prescribed as an anti-inflammatory reliever in patients with intermittent or infrequent symptoms and has been shown to reduce severe exacerbations by 40–50% and reduces long-term steroid load.

‘Similarly for COPD, the goal of treatment is to optimise function through symptom relief and reduce the risk of exacerbations,’ she explains. ‘While pharmacological therapy has not been shown to slow decline in lung function over time, inhaled therapy can reduce exacerbation frequency, and improve symptoms and exercise tolerance. COPD is the leading cause of potentially preventable hospital admissions.’

New combinations for people with frequent exacerbations with uncontrolled conditions despite optimised treatment include ‘triple therapy’ inhalers which contain a corticosteroid (anti-inflammatory) and two long-acting bronchodilators (βeta2 agonists and muscarinic antagonists), only one of which is approved for use in asthma.

‘When used as recommended in this group, these inhalers are more effective than dual combinations but the benefit versus risk must be carefully considered by prescribers,’ according to Prof Saini.

Asthma and biologics

The advent of biologics to treat severe asthma has been another important shift in treatment, says Ms Rigby.

Biologics including omalizumab, benralizumab, dupilumab, and mepolizumab are available on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for patients with severe allergic and eosinophilic asthma. They can reduce the need for oral corticosteroid (OCS) bursts and maintenance therapy, minimising the cumulative toxicity of OCS.

Biologics including omalizumab, benralizumab, dupilumab, and mepolizumab are available on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for patients with severe allergic and eosinophilic asthma. They can reduce the need for oral corticosteroid (OCS) bursts and maintenance therapy, minimising the cumulative toxicity of OCS.

As little as four or five short courses of prednisolone or prednisone can increase the risk of osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes, cataracts, weight gain, and cardiovascular disease. The risk of long-term toxicity increases with cumulative doses exceeding 1000 mg, Ms Rigby explains.

‘The steroid-sparing effects of biologics have been well demonstrated, so pharmacists can discuss this valuable addition to treatment strategies and early referral to respiratory specialists.’

Up to 80% of people with asthma also have allergic rhinitis and 40–50% of people with allergic rhinitis have asthma, says Ms Rigby. Achieving better control of allergic rhinitis through use of intranasal corticosteroids (INCS) will help improve asthma control.

‘So,’ she says, ‘the opportunity exists in pharmacies to talk about co-existing asthma and allergic rhinitis and how to better manage both conditions. Many patients with intermittent hay fever will self-select oral antihistamines or even nasal decongestants.’

But the evidence says INCS are first-line therapy. ‘And now, she adds, there are two products which combine INCS and intranasal antihistamines.’

Inhalers also create environmental impact and a carbon footprint. So a campaign through the Return of Unwanted Medicines (RUM) to bring inhalers back to the pharmacy for appropriate disposal is warranted, according to Ms Rigby.

While dry powder inhalers have less environmental impact, the best inhaler is the one a patient uses, and uses correctly.

‘I support the new reusable Respimat inhalers,’ she advises. ‘But pharmacists need to help patients understand how to load and prime the device each time or ask the patient to bring their device with them when repeats are dispensed.

‘The over-reliance of SABAs for asthma management, which are mostly pMDIs, creates a massive environmental impact.’

Correct inhaler use

Ms Rigby maintains that 94% of patients don’t use their inhalers correctly.

‘Alarmingly, many health professionals cannot correctly demonstrate use of all inhalers. Pharmacists need to be confident to demonstrate all the devices. And pharmacies should have placebo devices to demonstrate to patients.’

Videos are available on the National Asthma Council and Lung Foundation Australia websites to show to patients.11,12

Ms Rigby advises printing out the device checklist and highlighting the steps patients need to do better.

‘Helping patients understand the importance of each step can improve inhaler technique. We know that technique declines in as little as 1 or 2 months, so we need to check technique at every opportunity.’

One of the challenges for patients with the use of multiple different inhaler devices is remembering and mastering the different steps for each inhaler type. Ms Rigby says Home Medicines Reviews (HMRs) ‘are great for having a longer conversation with the patient and assessing inhaler technique in the privacy of their home. I spend about half an hour with patients just on inhaler technique and helping them understand why regular use of inhalers is so important.’

GPs with whom she works, also prefer Ms Rigby’s pharmacist assessment of whether an inhaler device is the right one for individual patients.

Disease differentiation

The differentiation between asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis in the early stage of disease is extremely important for the adoption of appropriate therapeutic measures.13

It is important for pharmacists to realise, says Prof Bosnic-Antecivich, that diagnoses of these chronic obstructive lung conditions can be a challenge in real life which are not always correct at the start. ‘Due to both unique and in some cases overlapping features of these diseases, it might be necessary to correct the patient’s management path if we see that the current strategy is not working as we would expect.’

It is important, therefore, to refer the patient back to the doctor if the pharmacist feels something is not quite right. ‘Most GPs will appreciate the support and care,’ she says.

Climate considerations

In respiratory presentations, climate can be a major factor.

Thunderstorm asthma can occur suddenly and has been described overseas in the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Italy, Canada, the United States, Mexico, and Iran.14–19

It is expected to increase in frequency and severity with climate change.20 Locally it occurs largely in south-east Australia in spring or summer when there is grass pollen in the air and the weather is hot, dry, windy, and stormy.21,22

The world’s largest epidemic thunderstorm asthma event occurred in Melbourne on 21 November 2016 killing 10 and hospitalising 3,400 people.23

Bushfires are another impacting climate manifestation,24 as is mould.25 Environmental changes may have possible impact on asthma development and ongoing management, says Prof Saini, given that asthma can develop through gene-environment interactions.26

‘If one considers aeroallergens that in some cases trigger asthma, heightened temperatures can extend the duration of pollen seasons and altered chemical reactions of pollutants (ozone particulate matter etc) can also enhance exposure to aeroallergens, leading to a greater likelihood of allergen-induced symptoms or even thunderstorm asthma.27

‘Indeed, it has been suggested that air pollution in many locations in Australia is at levels considered unsafe for respiratory health.’28 Prof Saini warns that education and awareness about being alert about air pollution levels is essential for those living with asthma.

What can pharmacists be doing?

Until PSA’s Respiratory Care Community of Specialty Interest (RC CSI) white paper provides a roadmap forward later this year after mapping the current situation in Australia, pharmacists need to be on top of multiple different inhaler devices and help patients remember and master the different steps for each inhaler type.

Pharmacists have the responsibility for non-prescription SABAs. They ‘therefore need to help patients understand the potential harm of over-reliance on SABAs for frequent symptom relief and the benefit of ICS for better control of their asthma’, Ms Rigby warns.

Prof Bosnic-Anticevich envisages a different, specialised strategy that pharmacists can deliver that includes their unique data through dispensing records and other tools they might have to create in a referring cycle that dovetails with GP prescribing.

Clearly, novel methods of improving asthma patients’ understanding of asthma are needed, concludes Prof Saini. ’Community pharmacies are well pivoted to address these common and modifiable behavioural risk factors that jeopardise asthma control; asthma may not have a cure, but it can certainly be well managed and controlled.’

In coming months the RC CSI will distribute online surveys to all pharmacists on respiratory disease management and all input will be critical to future development of the role of pharmacists in respiratory care.

References

- AIHW. Burden of disease. 2020. At: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/burden-of-disease

- AIHW. Asthma. Impact. 2020. At: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/asthma/contents/deaths

- AIHW. Allergic rhinitis (’hay fever’). 2020. At: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/allergic-rhinitis-hay-fever/contents/allergic-rhinitis

- AIHW. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). 2020. At: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/copd/contents/copd

- AIHW. Deaths in Australia. 2021. At: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life-expectancy-death/deaths-in-australia/contents/leading-causes-of-death

- AIHW. Admitted patient care 2016–17: Australian hospital statistics, in Heath services series no. 84. Cat. No. HSE 201. 2018. At: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/acee86da-d98e-4286-85a4-52840836706f/aihw-hse-201.pdf.aspx?inline=true

- Toelle BG, et al. Respiratory symptoms and illness in older Australians: the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study. Med J Aust 2013;198(3):144–8.

- Lung Foundation Australia. COPD the basics. 2018. At: lungfoundation.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Book-COPD-The-Basics-Nov2021.pdf

- Bronchiectasis Toolbox. What is bronchiectasis? At: bronchiectasis.com.au/bronchiectasis/bronchiectasis/definition

- AIHW: Bronchiectasis. 2020. At: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/bronchiectasis/contents/bronchiectasis

- National Asthma Council Australia. Asthma First Aid How-to videos. 2022. At: www.nationalasthma.org.au/living-with-asthma/how-to-videos

- Lung Foundation Australia. Inhaler device technique: Accuhaler video. 2022. At: https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/inhaler-device-technique-accuhaler/

- Athanazio R. Airway disease: similarities and differences between asthma, COPD and bronchiectasis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012;67(11)1335–43.

- Venables KM, Allitt U, Collier CG, et al.Thunderstorm-related asthma – epidemic 24/25 June 1994. Clin Exp Allergy 1997;27:725–36.

- D’Amato G, Liccardi G, Frenguelli G. Thunderstorm-asthma and pollen allergy. Allergy 2006;62(1):11–16.

- Wardman AE, Stefani D, MacDonald JC. Thunderstorm-associated asthma or shortness of breath epidemic: a Canadian case report. Can Respir J 2002;9:267–70.

- Rosas I, McCartney HA, Payne RW, et al.Analysis of the relationship between environmental factors (aeroallergens, air pollution and weather) and asthma emergency admissions to a hospital in Mexico City. Allergy 1998;53:394–401.

- Grundstein A, Sarnat SE, Klein M, et al. Thunderstorm associated asthma in Atlanta, Georgia. Thorax 2008;63(7):659–60.

- Forouzan A, Masoumi K, Haddadzadeh Shoushtari M, et al. An overview of thunderstorm-associated asthma outbreak in southwest of Iran. J Environ Public Health 2014;2014:504017.

- Harun N-S, Lachapelle P, Douglass J. Thunderstorm-triggered asthma: what we know so far. J Asthma Allergy 2019;12:101–8.

- National Asthma Council Australia. Thunderstorm asthma. 2022. At: nationalasthma.org.au/living-with-asthma/resources/patients-carers/factsheets/thunderstorm-asthma

- NSW Health. Thunderstorm asthma. 2017. At: www.health.nsw.gov.au/environment/factsheets/Pages/thunderstorm-asthma.aspx

- Thien F, Beggs PJ, Csutoros D, et al. The Melbourne epidemic thunderstorm asthma event 2016: an investigation of environmental triggers, effect on health services, and patient risk factors. Lancet Planet Health 2018;2(6):E255–63. At: www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(18)30120-7/fulltext

- AIHW. Data update: Short-term health impacts of the 2019–20 Australian bushfires. At: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/environment-and-health/data-update-health-impacts-2019-20-bushfires/contents/admitted-patients-hospitalisations/respiratory-conditions

- NSW Health. Mould. 2022. At: www.health.nsw.gov.au/environment/factsheets/Pages/mould.aspx

- von Mutius E, Martinez FD, Fritzsch C, et al. Prevalence of asthma and atopy in two areas of West and East Germany. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149(2 Pt 1):358–64.

- Rychetnik L, Sainsbury P, Stewart G. How local health districts can prepare for the effects of climate change: an adaptation model applied to metropolitan Sydney. Aust Health Rev 2019 Jan;43(6):601–10.

- Asthma Australia. Air Nutrition: https://asthma.org.au/air-nutrition/

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

Professor Margie Danchin[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

Dr Peter Tenni[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

How should we deprescribe gabapentinoids, according to the Maudsley Deprescribing Guidelines[/caption]

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more

Pharmacists have always prescribed, but they have the potential to prescribe much more