td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28513

[post_author] => 1703

[post_date] => 2025-01-20 13:19:22

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-01-20 02:19:22

[post_content] => With only two weeks before school resumes, now is the ideal time for pharmacists to help parents catch up with vaccinations for their children.

“As a parent of a four and six-year-old child, I know January is typically the time when kids are getting ready for the school year,” said Jacqueline Meyer MPS, owner of LiveLife Pharmacy Cooroy and PSA Queensland Pharmacist of the Year 2023. “Let’s make sure that includes updating vaccinations.”

Ms Meyer said encouraging parents to take advantage of this window of time could help overcome practical difficulties such as a busy lifestyle, while the availability of an increasing number of vaccines at pharmacies was especially helpful in regional areas where it may be more difficult to see a GP.

Research by the National Vaccinations Insight Project found that 23.9% of parents with partially vaccinated children under the age of five did not prioritise their children's vaccination appointments over other things, while 24.8% said it was not easy to get an appointment.

As well as holidays being free of the hustle and bustle of school routine, getting immunised during the holidays means children don’t have to miss a day of school if they have mild vaccination side effects, said Samantha Kourtis, pharmacist and managing partner of Capital Chemist Charnwood in the ACT and the mother of three teenagers.

Overcoming hesitancy

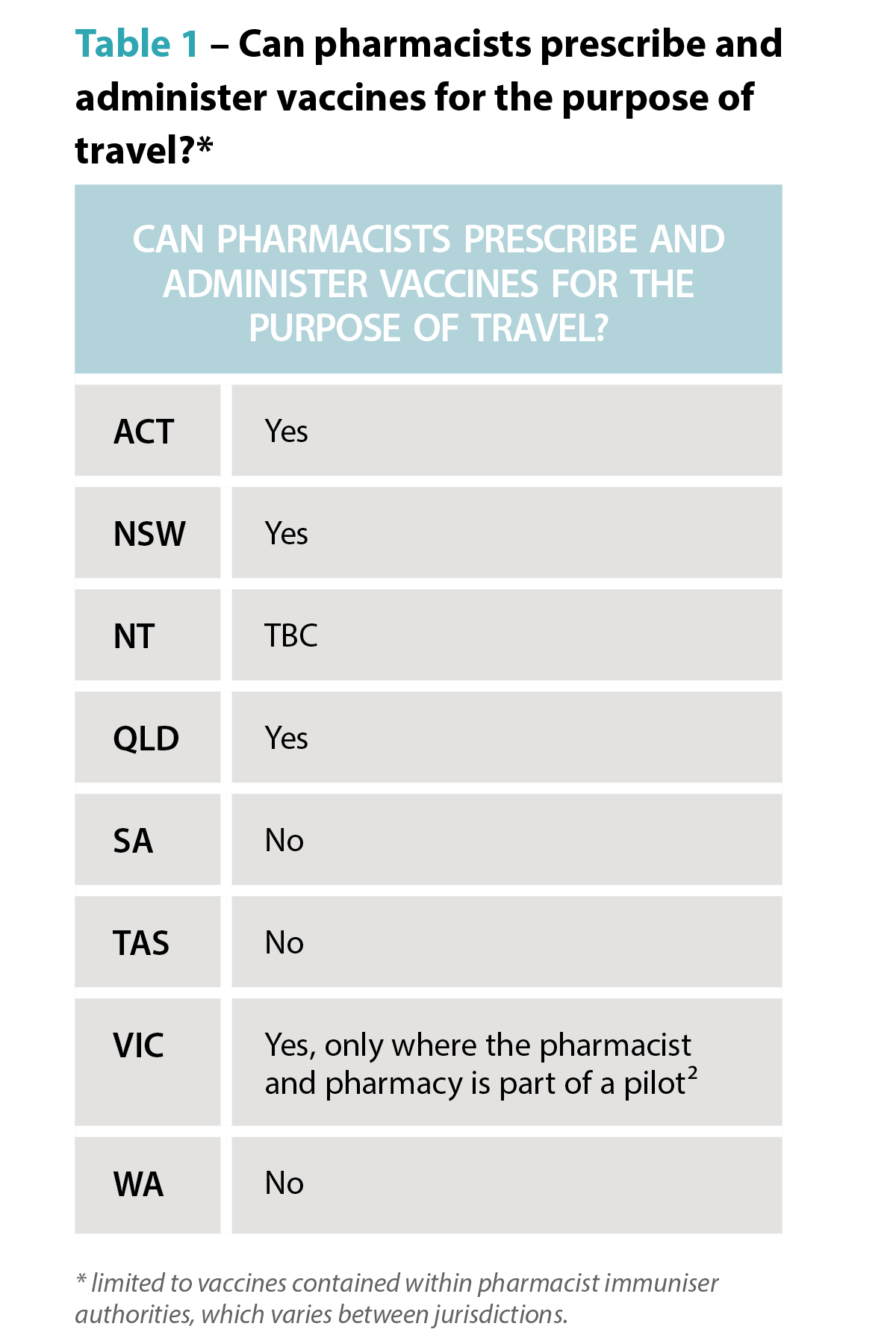

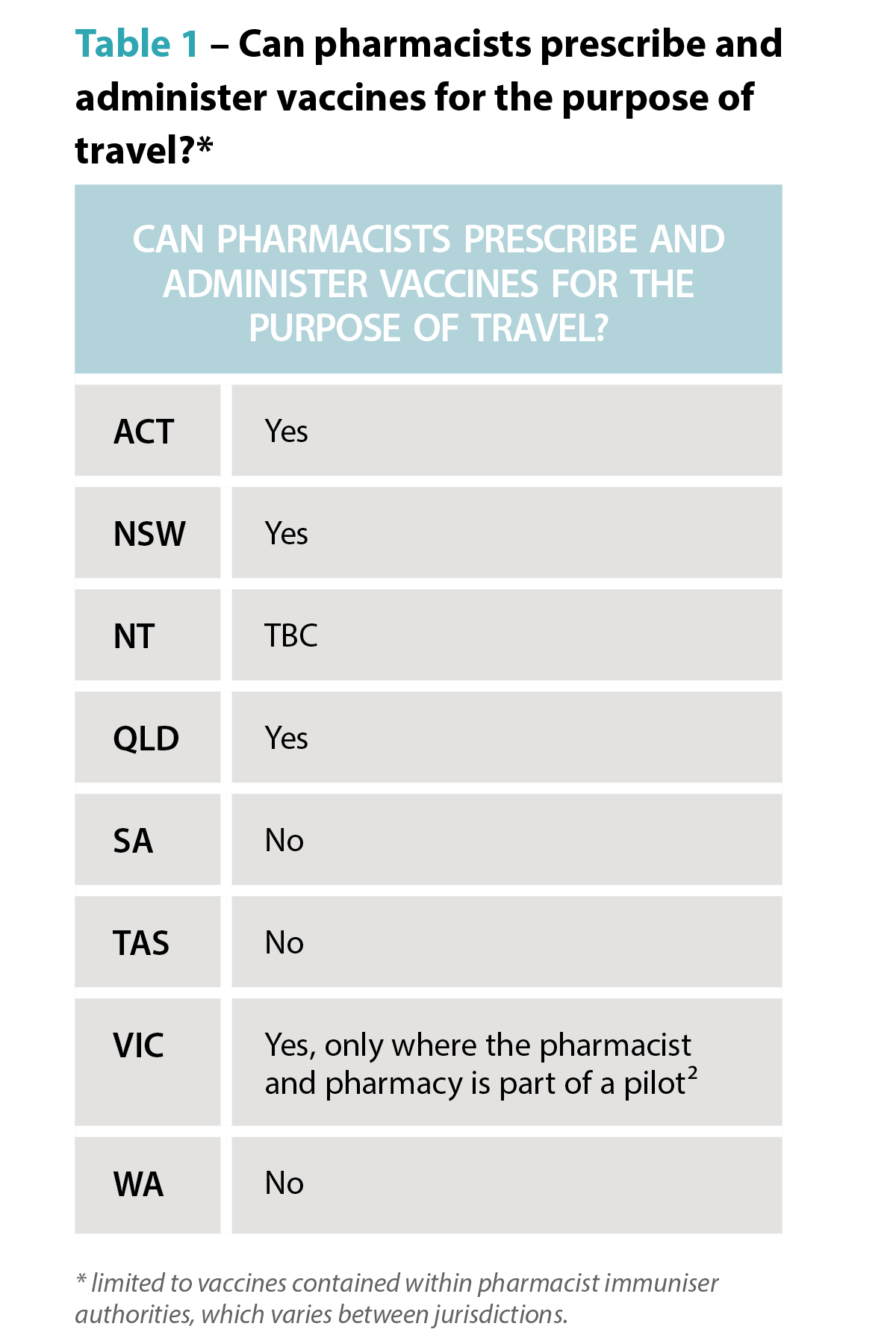

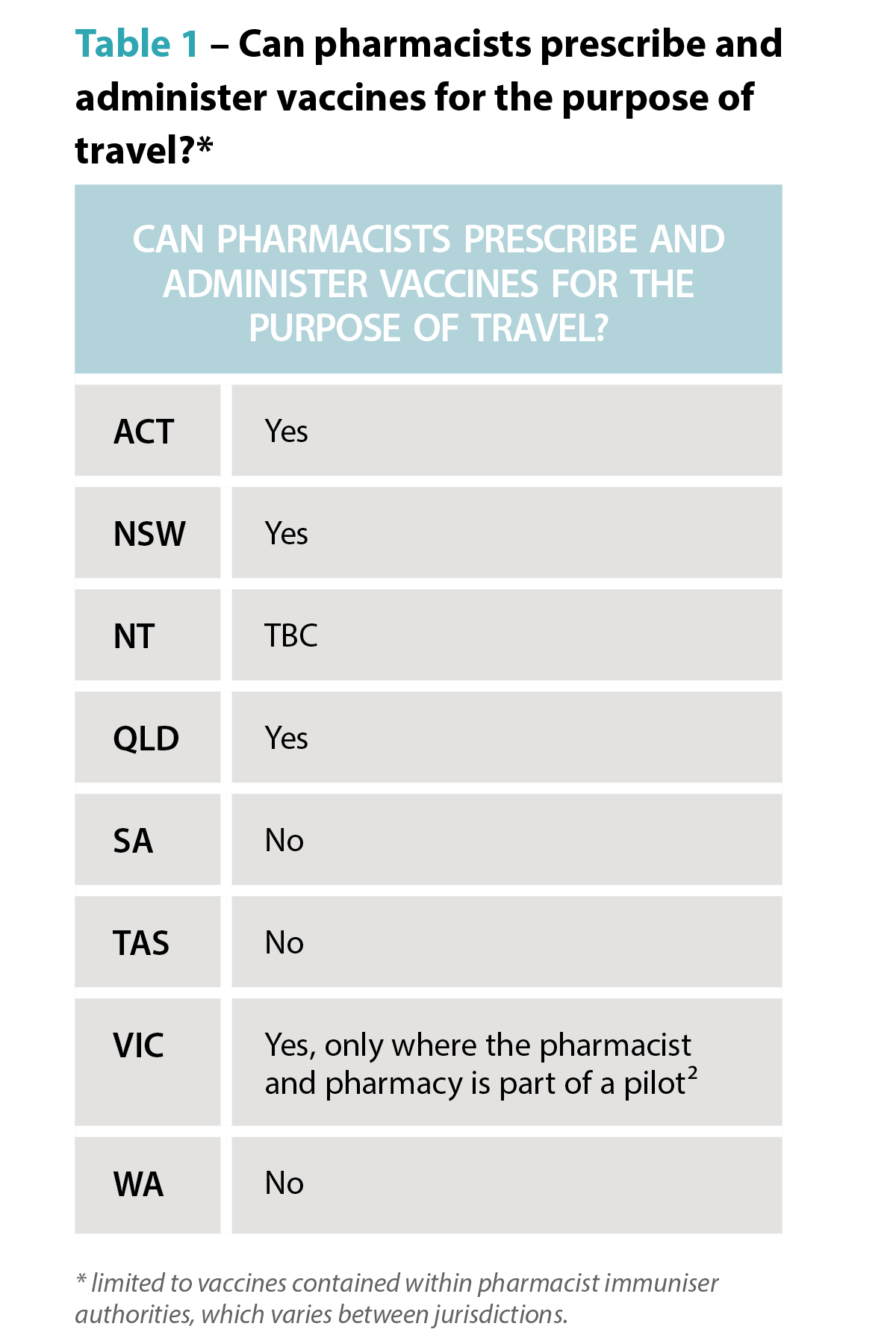

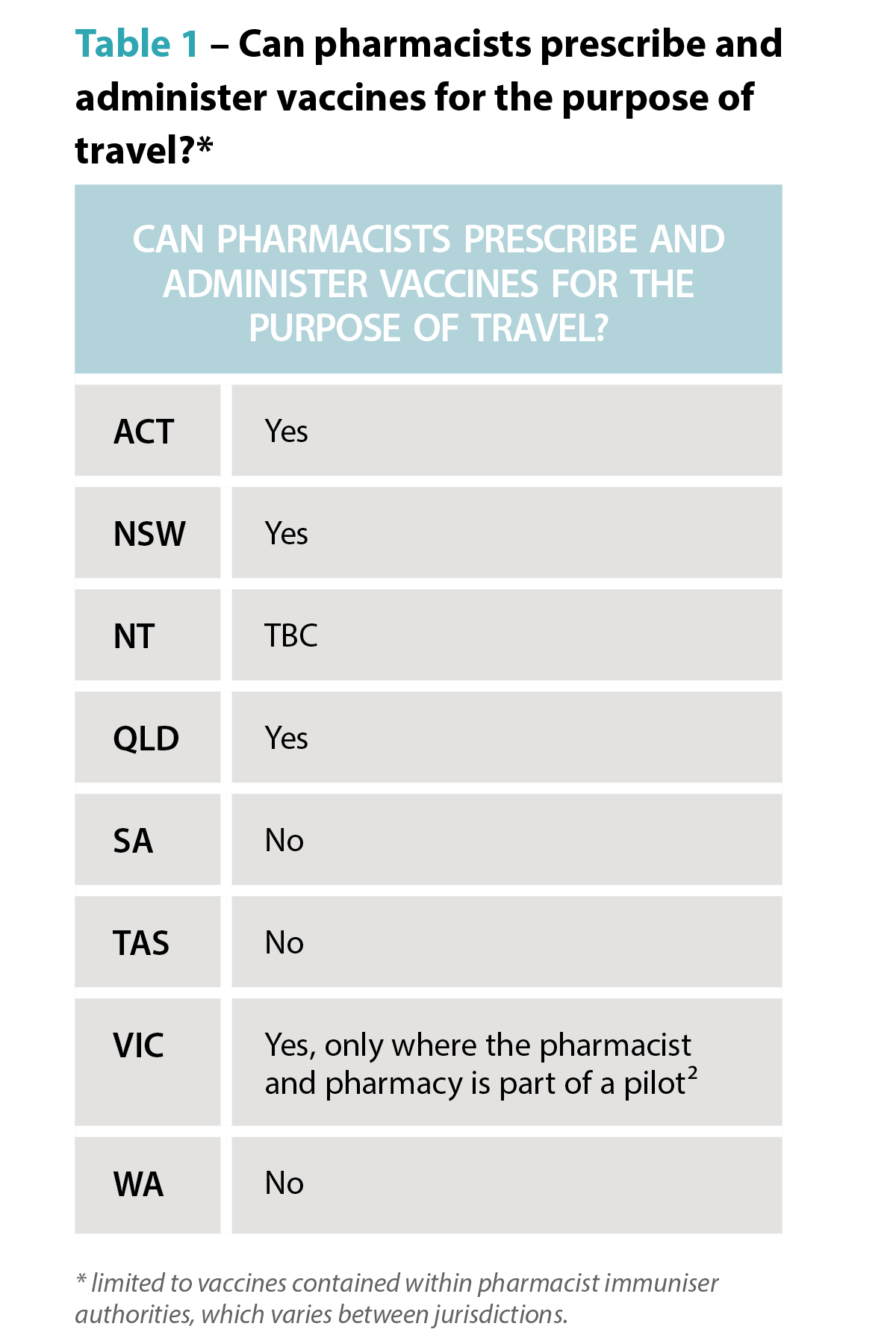

Ms Meyer said it was crucial that pharmacists familiarised themselves with the laws governing vaccinations in different states and territories so they knew what part they could play in boosting immunisation.

In most states and territories pharmacists may administer vaccines to children over the age of five – in Queensland that age is two years and, in Tasmania, in some cases, 10 years.

This can be most helpful for children who have missed out on immunisations through school programs, or from a medical clinic.

Concerningly, however, new research shows vaccination coverage among children in Australia has declined for the third consecutive year.

In 2020, fully vaccinated coverage rates were 94.8% at 12 months, 92.1 at 24 months and 94.8% at five years of age. In 2023 those rates were 92.8, 90.8% and 93.3% respectively.

Between 2020 and 2023, the proportion of children vaccinated within 30 days of the recommended age also decreased for both the second dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccine (from 90.1% to 83.5% for non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and 80.3% to 74.6% for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children) and the first dose of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine (from 75.3% to 67.2% for non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children children and 64.7% to 56% for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children).

While access issues played some part in the decline, vaccine acceptance or parents’ thoughts and feelings about vaccines and parents’ social influences have also been a factor, according to the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance.

Researchers found 60.2% of parents felt distressed when thinking about vaccinating their children.

Pharmacist Sonia Zhu MPS, of Ramsay Pharmacy Glen Huntly, who has a four year old child, said she often has conversations with parents who feel anxious about vaccination.

“Whenever a parent is concerned, I ask them what is making them feel worried and then I am able to talk to them about the risks of the disease as opposed to the vaccine,” she said.

“I can assure them that vaccinations are just like a practice exam for your immune system and that, if their child gets the disease, they will recover better and more quickly if they are vaccinated.”

Mrs Kourtis said it was also important to reduce vaccination anxiety among children with a friendly healthcare environment, especially for younger children.

“We have regular colouring competitions, fairy doors, fun stickers and a donut stool they sit on to have their vaccination,” she said.

“We also talk to parents about what their child needs before being vaccinated. That may be to wear headphones, for example, or other measures for children who are neurodiverse.”

While Ms Zhu said lollipops were offered to children and teens, Ms Meyer said cartoon images, stuffed toys and devices that acted as distraction tools were other accessories used in pharmacies to help create a calm environment.

The teenage challenge

Vaccine rates in adolescents have also declined. Between 2022 and 2023, coverage decreased for having at least one dose of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine by 15 years of age (from 85.3% to 84.2% for girls and 83.1% to 81.8% for boys); an adolescent dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine by 15 years of age (from 86.9% overall to 85.5%) and one dose of meningococcal ACWY vaccine by 17 years of age (from 75.9% overall to 72.8%).

“We certainly have nowhere near the uptake of meningococcal B vaccine we would like in Queensland,” said Ms Meyer.

According to the Primary Health Network Brisbane South, in the 15 to 20-year-old cohort, just under 14% have been immunised, leaving approximately 386,000 eligible adolescents unvaccinated.

The Queensland MenB Vaccination Program announced this year provides free vaccines to eligible infants, children and adolescents, and is the largest state-funded immunisation program ever implemented in the state.

With pharmacists able to administer all of these vaccinations between year 7 and year 10, Ms Meyer sees a clear opportunity to communicate the benefits of vaccination to parents.

“I think pharmacists could reach out to local schools and offer to conduct educational sessions,” said Ms Meyer. “Community pharmacies often employ teenagers for casual or junior shifts so it may start with simply talking to existing staff that may fit the eligibility criteria for demographic.”

Mrs Kourtis said community pharmacists were well placed to have health promotions in store and on social media.

“They can also try to partner with local community and sporting organisations to promote vaccination through them,” she said.

[post_title] => Boosting childhood vaccination rates in the holidays

[post_excerpt] => With only two weeks before school resumes, now is the ideal time for pharmacists to help parents catch up with vaccinations for their children.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => boosting-childhood-vaccination-rates-in-the-holidays

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-01-20 16:09:35

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-01-20 05:09:35

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28513

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Boosting childhood vaccination rates in the holidays

[title] => Boosting childhood vaccination rates in the holidays

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/boosting-childhood-vaccination-rates-in-the-holidays/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28514

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28280

[post_author] => 9500

[post_date] => 2025-01-18 08:00:52

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-01-17 21:00:52

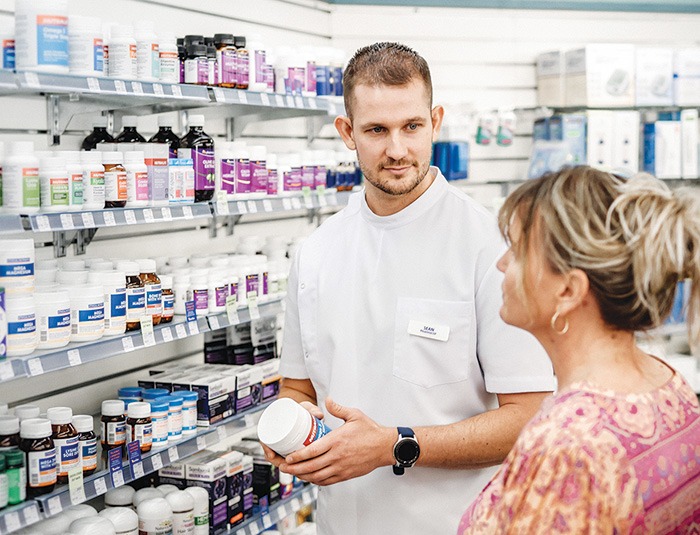

[post_content] => Turning informal advice into a structured consultation service: pharmacy-based travel health services take flight.

Australians love to travel and they take off to all parts of the globe, whether it be safaris in Africa, a bargain trip to Bali, visiting family in India or cruising through the icebergs within the Arctic Circle.

But as the average age of travellers, population density, pollution and zoonotic diseases increase, so, too, do health risks associated with travel.

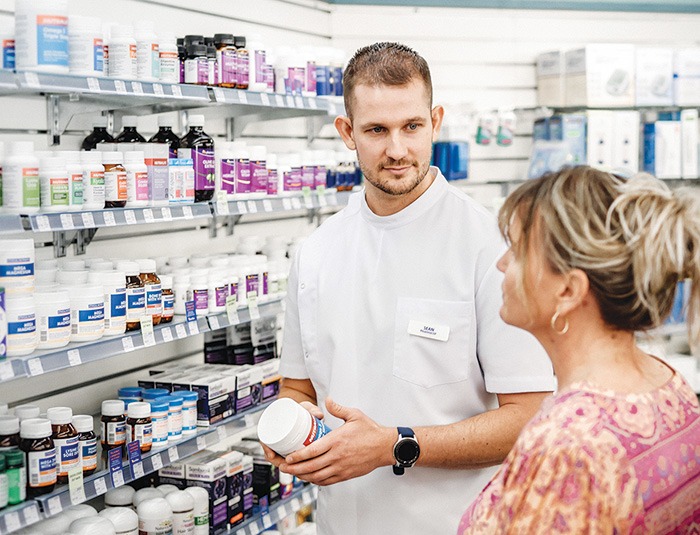

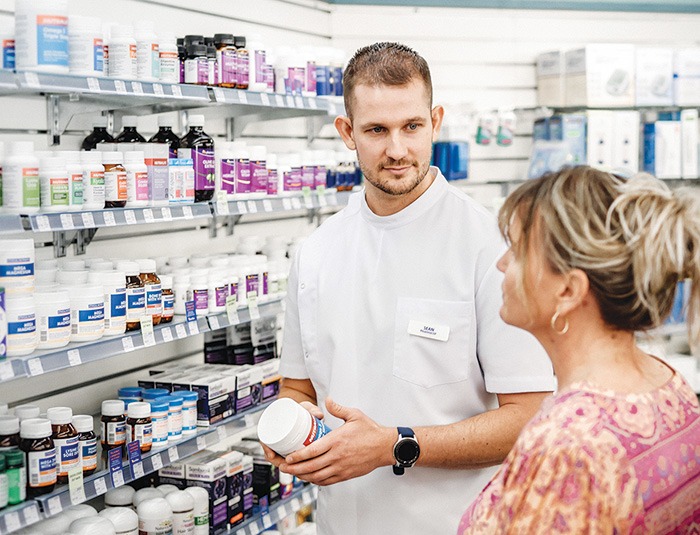

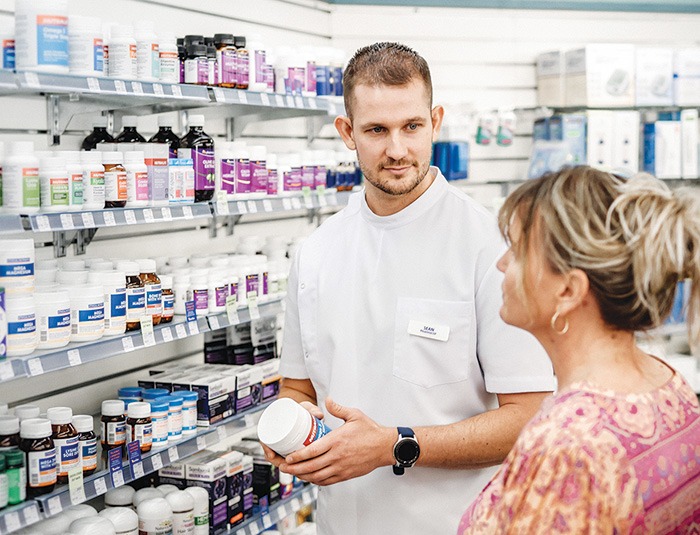

Pharmacists have long provided ad hoc advice for travellers in response to patient queries, whether it be guidance on how to store medicines during transit or encouraging patients to see a GP, or dedicated travel doctor service in major cities, for vaccination.1

But with more Australians jetting off to more locations more frequently, more travel health services are needed. Some pioneering pharmacists are leading the way. Enabled by an increasing range of vaccines pharmacists can both prescribe and administer as well as formal pilots and programs from state governments, community-pharmacy based travel health consultation services are taking flight.

How does a formal travel health service differ from ad hoc advice?

Put simply, its more comprehensive. It considers a much wider range of risks than the patient may self-identify and makes recommendations to the traveller proportional to their individual needs.

‘Outside of a formalised program like the Victorian Community Pharmacy Statewide Pilot project,2 the pharmacist may not go into as much depth about [travel health] matters because there’s an expectation the consumer’s GP will have that discussion when a patient asks about vaccines,’ says PSA Victorian State Manager Jarrod McMaugh MPS.

It means pharmacists ‘instead of picking and choosing pieces of information they’re going to add on to a consultation before referring and saying “go to see your GP for these things”, they’re going to address them all directly in a travel health service’, he says.

And to be comprehensive the service needs a deep understanding of the traveller(s), when/where they are going, how they are going to get there – e.g. cruise, fly, drive, trek – and the types of things they’ll do when they are there.

Getting started

Establishment or formalisation of any service has common features: staff training, developing standard operating procedures, setting up documentation systems and advertising. However, a travel health service has two additional aspects, which are critical to success.

Firstly, the practitioners need to really wrap their heads around international travel, the health risks a person is likely to encounter and how to craft a valuable consultation for each traveller.

‘Some pharmacists are avid international travellers, and will have generated substantial knowledge of destinations, transport routes and product availability at pharmacies overseas. This expertise is advantageous in providing bespoke, individualised advice,’ Mr McMaugh says.

‘For example, Australians are often surprised by the high cost of sunscreens overseas, or how unpleasant the taste of oral rehydration products available in other markets are.’

‘Additionally, people often overlook prohibitions on carrying common medicines through common transit points such as Middle Eastern or Asian airport hubs.’

These kinds of insights may not be front-of-mind for travellers when booking in for a consultation, but they are important for risk mitigation and highly valued.

Also important is anticipating risks for which travellers may not be alert. For example, a family holiday to a Thailand beach resort may initially seem lower risk, but activities and excursions where you interact with wildlife such as monkeys are common and carry zoonotic infection risk.

For pharmacists who do not have this knowledge from primary experience, seeking these reflections from colleagues or through careful listening with patients is essential.

For pharmacists who do not have this knowledge from primary experience, seeking these reflections from colleagues or through careful listening with patients is essential.

Structuring a consultation is something each practitioner needs to find their own way to master. Unlike other services, the approach to these longer consultations isn’t so black and white.

Compared to other expanded scope programs, travel health requires mastering the navigation of the grey.

One of the hundreds of pharmacists offering a travel service under the Victorian pilot is Melbourne’s Tooronga Amcal Pharmacy owner Andrew Robinson MPS, who reflected that ‘[with a UTI treatment service], we follow a protocol guideline and it’s more straightforward to undertake’. With travel, it is like a Pandora’s box that you can open and find you going all over the place with a whole lot of different destinations, a whole lot of different complications, a lot of different needs.’

Finding prospective travellers

A common theme with all pharmacists contacted by AP is that the identification of patients who would benefit from the service has initially been more successful through conversations in patient interactions than via formal advertising.

The trigger for knowing a patient could benefit from a sit-down travel health consultation with a pharmacist could be anything, Mr McMaugh notes.

‘It can literally be a comment in passing: ‘My son is about to travel overseas for the first time.’

Other queries could be related to how to carry medicines safely overseas, or interest in medicines for motion sickness.

Andrew Robinson describes the trial as a ‘significant endorsement by health regulators that pharmacists are capable of delivering more complex services.

‘Before actually doing an appointment, you’ve got to tease it out a bit first. It’s not like some of the other pilot programs that we’ve done, which are very, “you’ve got a urinary tract infection. You fit the criteria. We can undertake the consultation”.’

‘In contrast, you almost need to do a [travel health] consultation to find out whether you need to refer them on. So, I try and garner that before. But I think if we boil it down and keep it simple, the reality is there’s plenty of people out there who are not thinking about travel health that need a typhoid vaccine and a bit of a conversation,’ he said.

Mr Robinson identified that consumers who, at short notice, book a trip to south-east Asia and don’t plan a GP visit have particularly welcomed his travel health consultations.

Mr Robinson identified that consumers who, at short notice, book a trip to south-east Asia and don’t plan a GP visit have particularly welcomed his travel health consultations.

‘We see this particular pilot really looking at the high-risk patient, the person who sees a cheap flight to Indonesia and in 3 weeks’ time they’re gone. They think of it as just a great way to relax and give very little thought to the risks associated with that travel.’

Susannah Clavin MPS, the owner of the Marc Clavin Pharmacy at Sorrento on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula, regularly discusses travel health with patients and consumers, and has had success with online bookings.

‘Most [patients] were heading to south-east-Asia. They are all very time-poor, so if the pharmacy is closely located to their home or workplace then I think they will appreciate the convenience. Being able to book online, too, is a bonus.’

Like Mr Robinson, Ms Clavin had also identified patients through conversations at the dispensary.

‘One of the patients had a prescription for the vaccine and asked us for a quote,’ recalls Ms Clavin. ‘We gave the quote and mentioned that we could also administer the vaccine, for a fee. [The patient] was very keen to save a trip to the doctor.’

Fee-for-service

How much should the service charge? While each business needs to make its own decision based on the costs of delivery and business policies, experience in travel doctor clinics and within pilot sites shows consumers are willing to pay for the consultation service, which may include administration of vaccines.

When AP spoke to Mr Robinson, he had conducted about a dozen travel health consultations, charging $50 for a half-hour consultation. Families travelling overseas, he says, have found the consultations particularly attractive because the pharmacist can give advice to an entire family in one appointment.

Looking to the future

Feedback from the Victorian trial shows an effective travel health consultation service is a good fit with pharmacies that have a well-integrated vaccination service, according to Mr McMaugh.

‘If you’re doing the occasional vaccine, you have to change gears, going from doing whatever other services or dispensing you were doing, to administering the vaccine and then coming back into the retail and dispensing space,’ he says.

Mr Robinson hopes travel health consultations become a permanent fixture in the service landscape for pharmacy.

‘Travel is all about having fun. But we need to make sure it stays fun, and you stay healthy, because otherwise it’s a very expensive holiday.’

The rise of zoonotic diseases

The rise of zoonotic diseases

Where a person is travelling to and where they are staying matters. A trip to Zimbabwe to see Victoria Falls has a very different risk profile to a walking safari at remote campsites. Similarly, holiday resorts in south-east Asia next to agricultural fields have a different risk profile to city hotels.

Recent decades have seen the rise and reemergence of viral zoonotic diseases.4 The growth of tourism has led to land changes, travel patterns and farming practices which increase the risk of zoonotic diseases, including novel and well-established pathogens.⁵

Travellers and health professionals alike need to keep abreast of these trends. Rabies is a good case in point. The USA continues to log around 4,000 animal rabies cases each year, with >90% of cases from bats, raccoons, skunks and foxes – a shift from the 1960s where dogs were the primary rabies risk to humans.⁶ In contrast, dog bites are the predominant source of rabies infections in Africa.⁷

Karen Carter FPS, partner of Carter’s Pharmacy Gunnedah and owner of Narrabri Pharmacy in north-west NSW, can now offer rabies vaccinations.

‘You think of exotic animals for rabies but sometimes it’s dogs that people are at risk of being bitten by,’ Ms Carter says.

The vaccine isn’t cheap, so considering the exposure risk and access to post-exposure prophylaxis is important when discussing the benefits of the vaccine with patients.

‘We had a gentleman travelling to Africa and then on to South America for his work in the agriculture industry, so we recommended he get the rabies vaccine.’ Ms Carter says. In fact, he not only got the rabies vaccine administered, but the hepatitis A and typhoid vaccines as well before he left.

‘We were also able to refer him to a Tamworth GP clinic for his yellow fever vaccines, Ms Carter adds. ‘He thought it was great that we could do all but one of his vaccines in the pharmacy.’

Other zoonotic infections, such as mpox, avian influenza and Japanese encephalitis also have changing patterns of transmission and distribution, which increasingly require consideration in travel health services.

Case study

Dat Le MPS Owner, Priceline Pharmacy, Knox, Melbourne VIC

Dat Le MPS Owner, Priceline Pharmacy, Knox, Melbourne VIC

This traveller

Mrs L, a 62-year-old regular dose administration aid (DAA) patient, is living with gastro-oesophogeal reflux disease (GORD), hypertension, atrial fibrillation, high cholesterol and osteoarthritis in the knee.

Current medicines

This time Mrs L explains that it will be summer when she arrives in both south-east Asian countries.

Recommendations

Based on her travel plans, I recommend vaccination for:

Mrs L was advised she would have full protection from hepatitis A in 2 weeks and that it may be at least a week before the COVID-19 booster provided full protection.

She was also told that the vaccinations may cause sore arms, some redness, fever or chills.

While her typhoid vaccination would protect her for 3 years, she could have another COVID-19 booster in a year.

For the hepatitis A vaccine, a typical course is two doses – the first at day 0, and the second from 6 months later, ideally before 12 months, if she travels again within the year.

Rehydration preparations were also recommended, along with hand sanitiser, face masks and sunscreen for Mrs L’s holiday group tour to various sight-seeing locations.

When she collected her DAAs, we advised Mrs L how to store her medicines. She was pleased she didn’t need to make a GP appointment, organise vaccine prescriptions, collect them at the pharmacy and then take them back to the doctor to be administered. I reminded her that we would call her about her second hepatitis A dose to complete her course.

We put a note on her next DAA collection asking about her holiday and any problems she may have had such as diarrhoea or tablet storage problems.

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28126

[post_author] => 9499

[post_date] => 2025-01-17 08:00:19

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-01-16 21:00:19

[post_content] => Case scenario

Mrs Johnson, a 65-year-old patient with hypertension, comes to the pharmacy to fill her repeat prescriptions for perindopril 4 mg and amlodipine 5 mg. You notice that Mrs Johnson is getting her repeats dispensed irregularly and offer her a blood pressure (BP) check. Mrs Johnson mentions that her BP has been poorly controlled, and she often forgets to take her medicines.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Already read the CPD in the journal? Scroll to the bottom to SUBMIT ANSWERS.

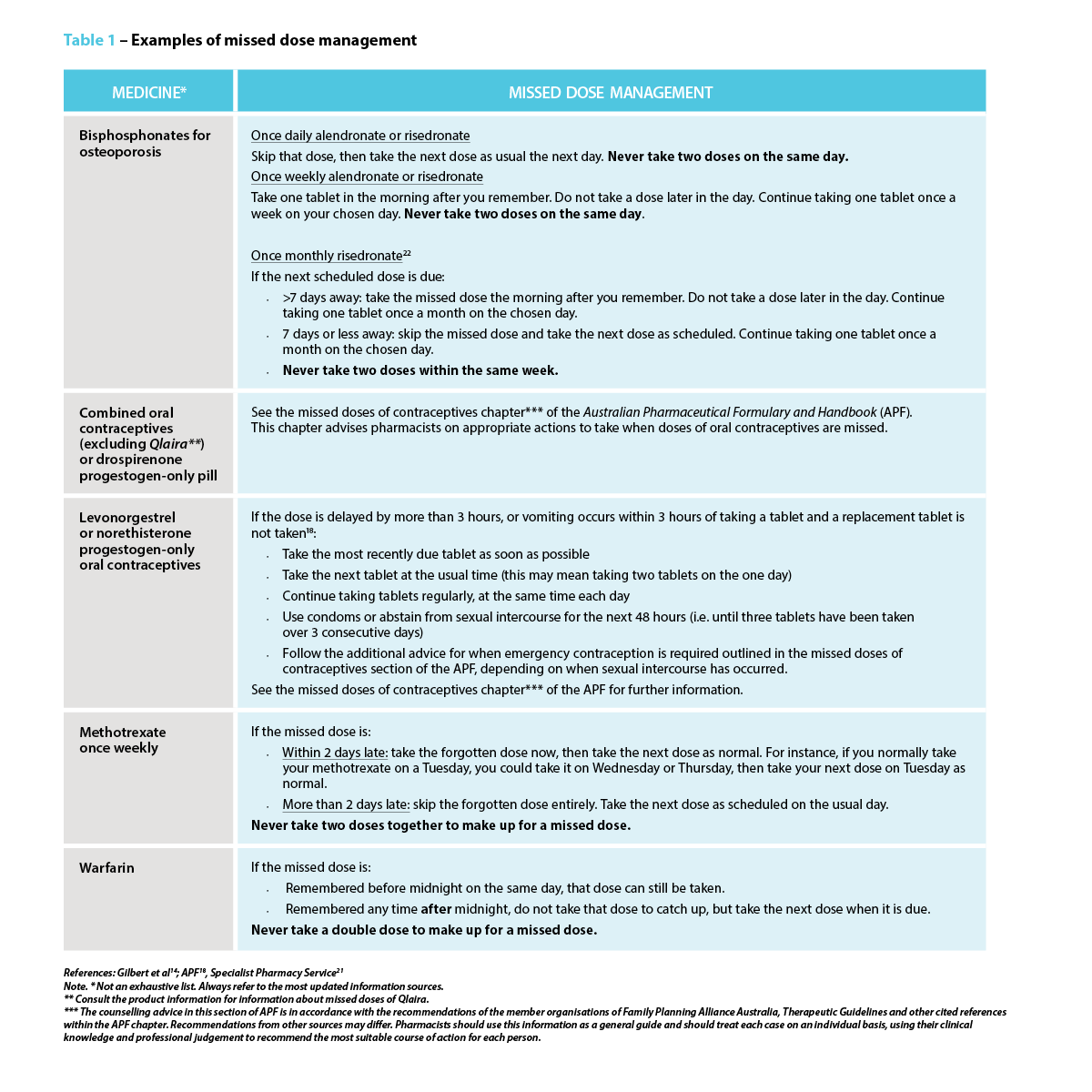

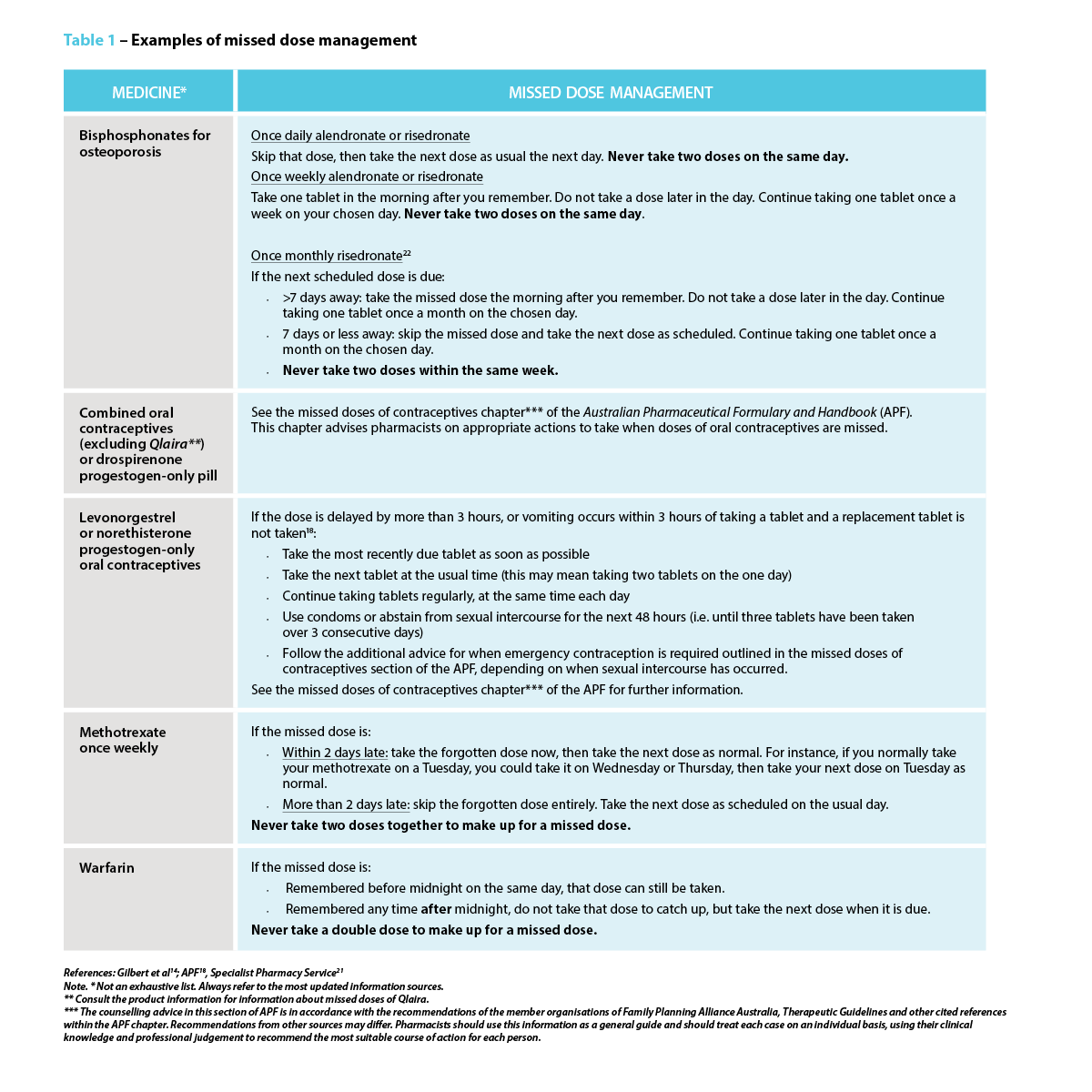

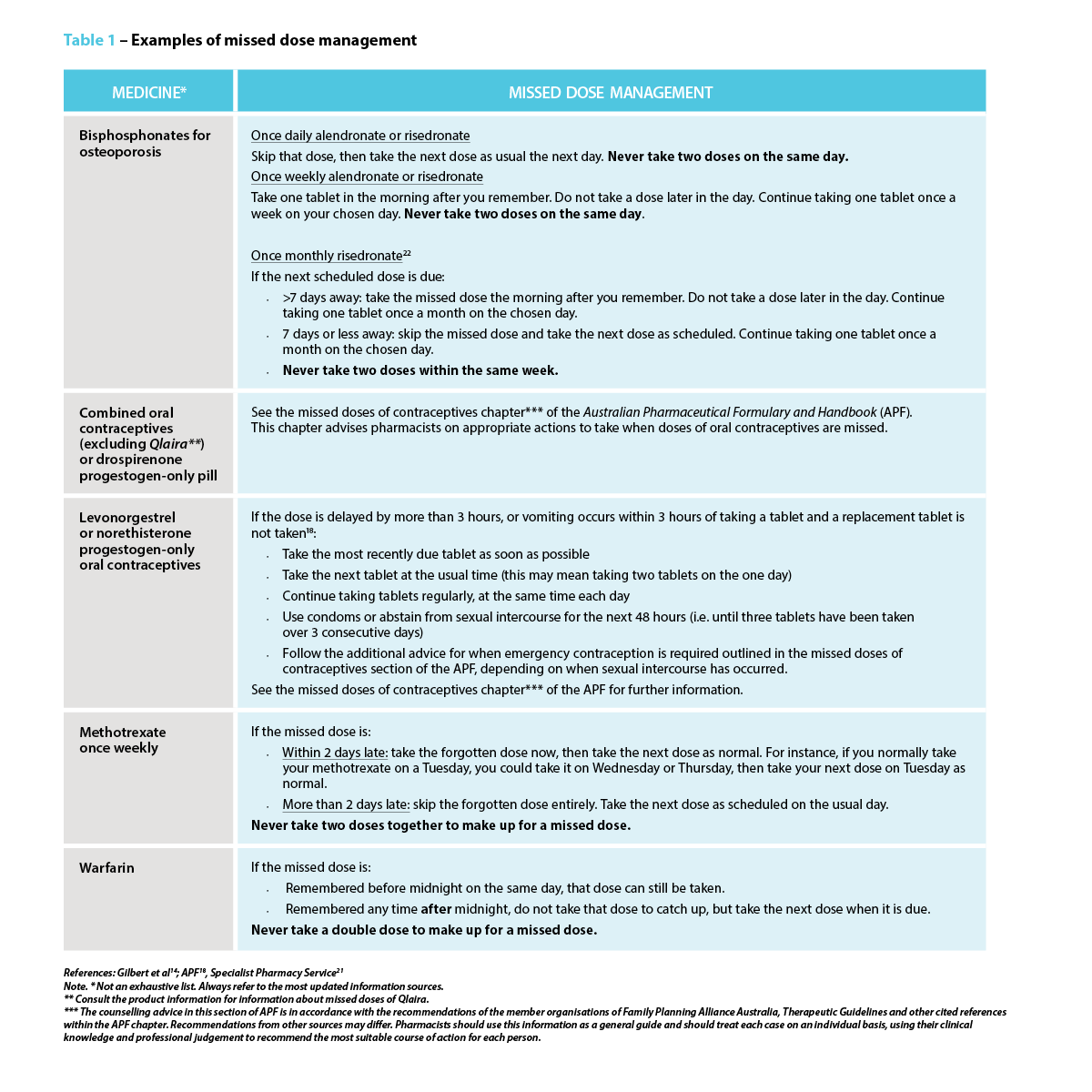

Missed or delayed administration of prescribed doses is a common concern in clinical practice and can be viewed under the framework of non-adherence, either intentional or unintentional. Medication adherence refers to the extent to which a person’s behaviour matches with the agreed recommendations from a health care provider.1 Adherence to prescribed dosing regimens is crucial for achieving the best therapeutic outcome.

Understanding the implications of missed doses and how to manage them effectively will assist pharmacists in providing clear and concise instructions to patients who miss a dose.

Different terminologies have been used to describe deviations from prescribed therapies. The terms adherence, compliance and concordance are often used interchangeably. However, compliance implies patient passivity in treatment decisions.2

Adherence and concordance suggest a more active and collaborative approach between the patient and healthcare provider, with concordance specifically highlighting the importance of mutual agreement in treatment decisions.3

Many underlying factors contribute to an individual’s adherence to their medication regimens. When considering the factors contributing to missed medicine doses, several patient-related aspects are particularly relevant for pharmacists. A patient may deliberately skip or delay a dose due to adverse effects, a perceived lack of effect, a lack of motivation, or if they believe the medicine is unnecessary.4 On the other hand, unintentional missed doses may be due to careless factors, including forgetfulness and limited understanding of the prescribed instructions.4

In a survey of patient adherence to medicines for chronic diseases, 60% of participants stated forgetfulness was the reason for missed doses.5 The study found that missed doses were more commonly reported by patients with vitamin D deficiency, followed by hyperlipidaemia.5

In a survey of patient adherence to medicines for chronic diseases, 60% of participants stated forgetfulness was the reason for missed doses.5 The study found that missed doses were more commonly reported by patients with vitamin D deficiency, followed by hyperlipidaemia.5

The reasons for missed doses may also be a combination of intentional and unintentional factors. For instance, patients who are not motivated to take a medicine may be more likely to forget to take a dose.4

Missed or delayed medicine doses are more likely when regimens are complex due to forgetfulness or when patients have fears and concerns about adverse drug reactions.6 Inadequate communication between healthcare providers and patients can also lead to confusion about medication regimens.6 For other individuals, busy schedules, frequent travel, major life events or interruptions to usual routines can disrupt their ability to take medicines consistently.7

The World Health Organization identified the following five interacting dimensions that affect medication adherence8,9:

Time-critical medicines are ‘medicines where early or delayed administration by more than 30 minutes from the prescribed time for administration may cause harm to the patient or compromise the therapeutic effect, resulting in suboptimal therapy’.10 An example is levodopa-containing products for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. A short delay can worsen symptoms and cause rigidity, pain and tremor, increase the risk of falls, as well as cause stress, anxiety and difficulty in communicating.11,12 Additionally, anticoagulants (e.g. enoxaparin) require strict adherence to dosing schedules, as clotting complications such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism can be life-threatening.13

Identifying whether a medicine is time-critical requires knowledge of the half-life of the medicine, as it is a major determinant of the fluctuation in inter-dose concentrations at a steady state.14 Half-life serves as guidance for making informed recommendations on what to do when a dose of medicine is missed. Four to five half-lives is a general rule of thumb used to approximate the time needed for a medicine to be considered eliminated from the body. At that time point, the plasma concentrations of a given medicine will reach below a clinically relevant concentration.15

Identifying whether a medicine is time-critical requires knowledge of the half-life of the medicine, as it is a major determinant of the fluctuation in inter-dose concentrations at a steady state.14 Half-life serves as guidance for making informed recommendations on what to do when a dose of medicine is missed. Four to five half-lives is a general rule of thumb used to approximate the time needed for a medicine to be considered eliminated from the body. At that time point, the plasma concentrations of a given medicine will reach below a clinically relevant concentration.15

While an occasional missed dose of most medicines will have little consequence on therapeutic outcomes, delays or omissions for some medicines can lead to serious harm. For some medicines, such as an antidepressant, it is possible to get withdrawal symptoms within hours of the first missed dose.16

Missing a dose of medicines with a short half-life and/or rapid offset of action in relation to the dosing interval may lead to periods of sub-therapeutic plasma drug concentrations, and therefore insufficient pharmacologic activity.17 In contrast, medicines with a long half-life stay in the body longer. As a result, missing a dose may not cause a significant drop in drug levels, reducing the risk of sub-therapeutic levels. However, it is important to note that the clinical effects of some medicines are not directly related to their half-lives.14 Some examples of these drugs are those that act via an irreversible mechanism (e.g. aspirin), an indirect mechanism (e.g. warfarin), and those that are pro-drugs or metabolised into an active form with a different half-life.14,18

The following are some examples of medicines requiring strict adherence to dosing schedules to avoid significant or catastrophic long-term patient impact:

1. Consumer Medicine Information

The first place a patient should be instructed to look for advice if they forget to take a dose of their medicine at the usual time is the Consumer Medicine Information (CMI) leaflet.

Most commonly dispensed medicines have a CMI leaflet with a section for when a dose is missed.19

Pharmacists should use the CMI to reinforce verbal advice for missed or delayed doses during their counselling as it would prepare patients for this eventuality. Pharmacists should provide approved CMI leaflets to patients when they start prescription medicines, and at each subsequent dispensing according to established guidelines as part of good dispensing practice.18

CMIs are usually included as part of the medicine packaging. Alternatively, the TGA website (www.ebs.tga.gov.au) provides access to the latest approved versions of the CMI and Product Information (PI) provided by the pharmaceutical companies for most of the prescription medicines available in Australia.

2. Other methods

2. Other methods

Other ways patients can obtain information about missed medicine doses include20:

3. General advice

When specific information is not available, the general advice to manage a missed or delayed dose is to take the missed dose as soon as it is remembered if the dose is less than 2 hours late.21 If the dose is more than 2 hours late21:

4. Do not take a double dose

It is generally not recommended to take a double dose to make up for a forgotten dose unless specifically advised.21

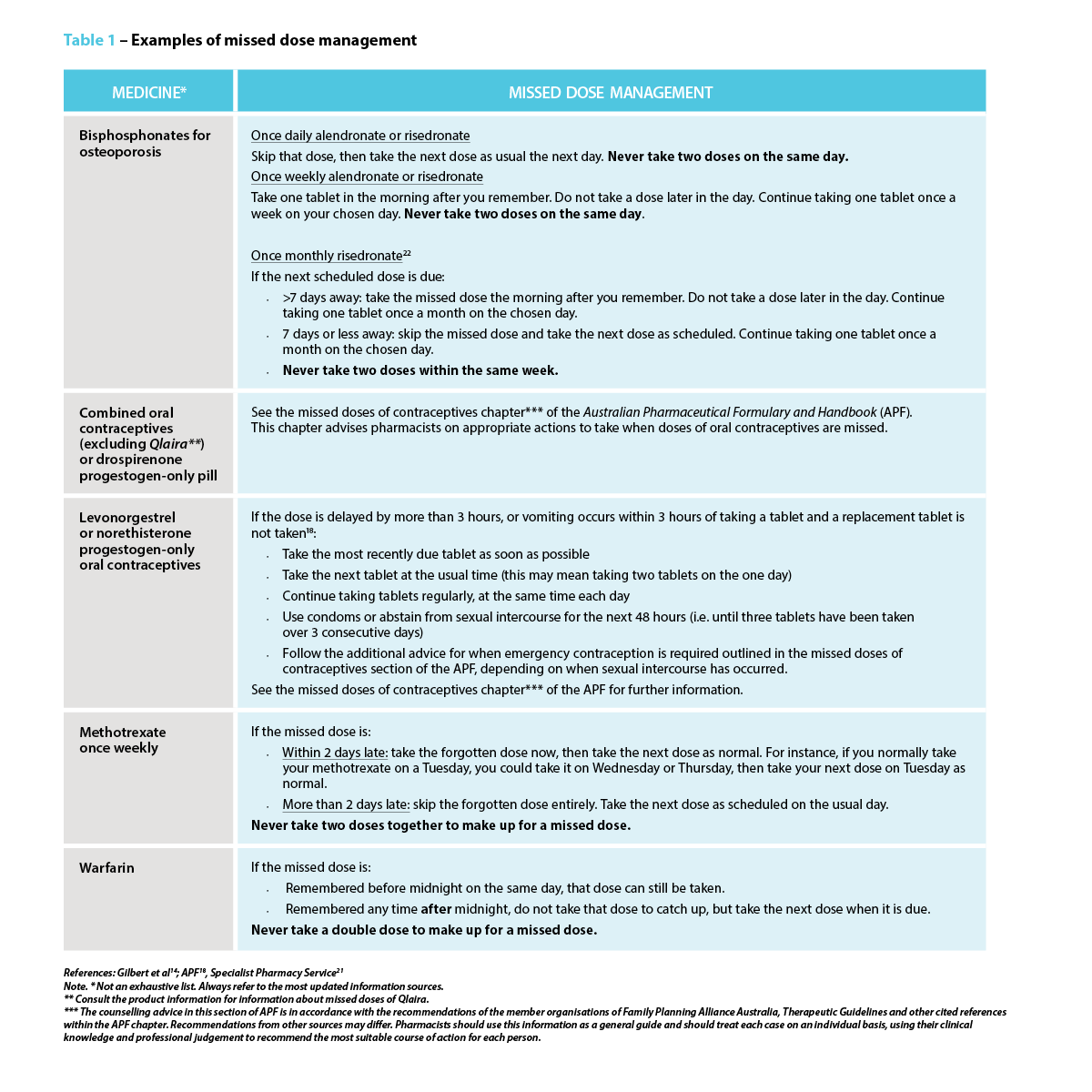

Many medicines have special instructions on managing missed doses. While it is not possible to include advice for all, Table 1 lists a few examples of some common medicines that pharmacists may encounter in their daily practice.

Strategies to prevent a missed or delayed dose

Strategies to prevent a missed or delayed dosePharmacists play a central role in preventing a missed or delayed dose. The strategies to avoid missed doses lie within the underlying cause.4 In addition to clearly explaining the dosing schedule, pharmacists should also focus on addressing the importance of taking medicine consistently as prescribed, particularly for medicines indicated for asymptomatic conditions or preventive measures, as the benefits may not be realised immediately. One study suggests using strategies such as motivational interviewing or another approach that addresses behavioural intention.4

Pharmacists should consider and act on the barriers patients might face in adhering to their medication regimen, which may include forgetfulness, complex or variable dosing schedules, adverse effects, or other health, dexterity or vision issues. This may require considerations of how the patient’s daily routine or lifestyle might impact their ability to take their medicines as prescribed (e.g. work schedule, travel). For instance, patients with cognitive impairment or those who forget to take their medicines may need memory triggers and a way to check whether or not they took them.4

Pharmacists can suggest the use of dose administration aids, pill organisers, sticky notes, alarm reminders on mobile phones, or “habit stacking” by associating medicine administration with a daily routine such as mealtimes and keeping the medicine visible.5 Some patients may find themselves frequently forgetting if they have taken their medicines, which is common for mundane behavioural decisions. One solution is to create a habit of recording each dose on a calendar, or if it is a pill bottle, simply flip it over every time a dose is taken as a visual reminder. Lastly, consider if alternative formulations (e.g. extended-release or combination formulations) are an option, as this could reduce the frequency of doses, thereby simplifying medication regimens.

Pharmacists can effectively manage missed doses by recommending appropriate action for missed doses and proposing tailored strategies that work best to address a specific barrier for patients. Pharmacists can provide patient education and counselling for medication adherence, collaborate with the patient’s primary care provider to discuss potential adjustments to their treatment plan, as well as offer dose administration aids. These actions can have a substantial impact on patient outcomes, including improved therapeutic outcomes, reduced health complications, improved quality of life and patient empowerment.

Missed medicine doses are common in practice, with potentially serious consequences for patient health, particularly when it comes to time-critical medicines. Pharmacists play a crucial role in providing advice for managing missed doses and supporting patients with their medication regimen management through the various strategies available.

Case scenario continuedYou review Mrs Johnson’s medication regimen and educate her on the importance of medicine adherence. You suggest using a pill organiser and setting daily alarms, and you talk to her GP about changing to a fixed-dose combination of perindopril/amlodipine. You also provide Mrs Johnson with a CMI leaflet and highlight for her the section that explains what to do when a dose is missed. When Mrs Johnson next returns to the pharmacy, you ask her how the interventions are helping. Mrs Johnson reports better adherence and thanks you for your help. Three months later, her blood pressure is well-controlled, significantly reducing the risk of future complications. |

Dr Amy Page (she/her) PhD, MClinPharm, GradDipBiostat, GCertHProfEd, GAICD, GStat, FSHPA, FPS is a consultant pharmacist, biostatistician, and a senior lecturer at the University of Western Australia.

Hui Wen Quek (she/her) BPharm(Hons), GradCertAppPharmPrac is a pharmacist and PhD candidate at the University of Western Australia.

Julie Briggs (she/her) BPharm, MPS, AcSHP

Hui Wen Quek is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship at the University of Western Australia.

[post_title] => Missed medicine doses: how pharmacists can help [post_excerpt] => Missed medicine doses are common in practice, with potentially serious consequences for patient health, particularly when it comes to time-critical medicines. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => missed-medicine-doses-how-pharmacists-can-help [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-01-20 09:01:58 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-01-19 22:01:58 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28126 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Missed medicine doses: how pharmacists can help [title] => Missed medicine doses: how pharmacists can help [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/missed-medicine-doses-how-pharmacists-can-help/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 28492 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28485

[post_author] => 8289

[post_date] => 2025-01-15 12:46:21

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-01-15 01:46:21

[post_content] => As temperatures soar, ensuring proper storage of medicines is more critical than ever. Here’s how heat impacts medicine safety and how pharmacists and patients can safeguard their efficacy.

Proper storage of medicines is vital to maintaining their efficacy and safety. But with Australia experiencing record-breaking temperatures, medicine integrity is at risk.

While it’s important to be aware of the effects climate change could potentially have on medicine safety, it may only exacerbate some of the problems we already have, said Dr Manuela Jorg, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Monash University.

Which drugs are most heat sensitive?

Medicine dosage forms such as liquids and solutions are more heat sensitive compared with solid compounds, said Dr Jorg. This includes injectable medicines such as insulin, vaccines or antibodies.

‘Sometimes short exposure to heat can have a detrimental effect but often it’s the longer exposure that can cause degradation of a drug,’ she said.

‘Degradation can lead to the medication becoming less effective or a molecule degrading into a different compound which could potentially be toxic and cause harmful side effects.’

How important is it to store medicine correctly?

A key aspect in protecting medicine integrity is ensuring medicines are stored correctly and not exposed to prolonged heat, sunlight or humidity.

Most medicines should be stored below 25⁰C and are tested by pharmaceutical companies at the recommended temperature they should be stored at for the full lifetime of their shelf life. They are also tested at temperatures of up to 40⁰C to ensure they remain stable.

Even with this added layer of testing, Pete Lambert, Director of the Monash Quality of Medicines Initiative, said that many patients may not be aware of the importance of keeping medicines at recommended temperatures and the potential dangers that not following these recommendations could create.

‘It's unlikely that once in the hands of the consumer, products will be stored in the right conditions for extended periods,’ he said ‘For example, simply leaving them in the car for a short period of time, in direct sunlight, or where temperatures can spike, could be problematic.’

Dr Jorg agrees. ‘As soon as we give medication to a patient, we have no control over what happens to the drugs,’ she said. ‘There have been several studies that show as soon as the medicine is in the hands of the patients, either transporting them home or storing them are often done in the wrong conditions.’

Signs of heat-affected medicines

Signs that medicines have been affected by the heat include changes in colour, consistency or smell; unusual softening or melting of solid forms of medicines, clumping of powders, and cracked or chipped coatings on tablets or capsules.

Heat exposure can also cause problems with medicine devices that involve a mechanism such as EpiPens, bronchial inhalers and autoinjectors. High temperatures can cause these to malfunction or even burst in the case of inhalers. Relying on these types of medicines that have been damaged by the heat could be fatal in an emergency.

How does hot weather impact the effects of medicines?

Another important aspect of extreme weather that’s important to consider is how higher temperatures can impact the effects of some medicines, said Mr Lambert. For example, patients who take medicines with a narrow therapeutic index such as warfarin, digoxin or lithium may be at risk of the drug becoming toxic if they become dehydrated in high temperatures.

Similarly, other medicines such as anticholinergic drugs that decrease the thirst response or inhibit sweating can cause patients to be at risk of dehydration and associated illness in hot weather.

Patients should be made aware of these risks and be advised to stay in cool environments, avoid going out in the hottest part of the day, and stay hydrated.

The challenge of online pharmacy providers

With most big banner pharmacy groups offering online ordering of medicines, pharmacists should provide guidance on maintaining medicine integrity where possible, said Mr Lambert.

‘If patients are going to order medicines online, it’s important that pharmacists advise patients to choose reputable providers,’ he said.’ Good providers will be aware of what kind of packaging the product needs to be in when it's shipped, so it’s adequately insulated for this period.'

If medicine is required to be kept in the cold chain, it should be shipped under refrigerated conditions, or with cold packs. If the product needs to be stored at temperatures less than 25⁰C packaging should be adequately insulated to ensure safe transport.

Patients should also know when their medicine is going to be delivered so they can be home and immediately take it into proper storage conditions once it arrives. If no one is home, patients could consider having a cooler bag at the front door where the medicine can be left, helping protect medicines from heat extremes.

What advice should pharmacists provide?

Many people may not know how to ensure their medicine remains safe and effective which is why education around medicine safety is really important, said Dr Jorg.

‘Pharmacists should explain proper storage techniques for particular medicines along with signs that a medicine may have been affected by the heat,’ she said. ‘It’s also important to make sure patients understand that if their medicines looks different to what it usually does, or they have any concerns to check with their doctor or pharmacist before taking it.’

Mr Lambert believes patients should understand medicine safety is often dependent upon adhering to the storage condition, which is on the carton or patient information leaflet, along with checking the expiry date.

‘It’s also important not to take the products out of the packaging they’ve been supplied in, because the stability and recommended storage conditions are based on the medicine being stored in the containers in which they’re supplied,’ he said.

Pharmacists should also explain the risks of leaving medicines in the car where temperatures can spike and recommend patients keep medicines in a cooler bag if they are travelling.

Ensuring patients understand how extreme heat can affect the way they handle their medicine, or how their medicine may affect them in higher temperatures is also important.

In the case of EpiPens, bronchial inhalers and autoinjectors, they mustn’t be left in hot cars or other environments that can become excessively hot, nor should they be exposed to direct sunlight. Keeping them well-insulated will help ensure the medicine and mechanisms to deliver the medicine are protected.

[post_title] => Maintaining medicine integrity in high temperatures

[post_excerpt] => As temperatures soar, ensuring proper storage of medicines is more critical than ever. Here’s how heat impacts medicine safety and how pharmacists and patients can safeguard their efficacy.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => maintaining-medicine-integrity-in-high-temperatures

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-01-16 15:27:54

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-01-16 04:27:54

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28485

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Maintaining medicine integrity in high temperatures

[title] => Maintaining medicine integrity in high temperatures

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/maintaining-medicine-integrity-in-high-temperatures/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28488

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28128

[post_author] => 9404

[post_date] => 2025-01-06 18:38:43

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-01-06 07:38:43

[post_content] => Case scenario

[caption id="attachment_28475" align="alignright" width="244"] A national education program for pharmacists funded by the Australian Government under the Quality Use of Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Pathology program.[/caption]

A national education program for pharmacists funded by the Australian Government under the Quality Use of Diagnostics, Therapeutics and Pathology program.[/caption]

Amna, 26 years old, is browsing the vitamins and herbal supplements section of the pharmacy, seeking a solution for her sleep problems. Over the past 2 weeks, she has experienced difficulty falling asleep at night and feels exhausted when she wakes up at 7 am to get ready for work. She also wants some information about melatonin, as some of her older colleagues have had success with it. Amna is an otherwise healthy young adult without co-existing medical comorbidities and is not currently taking any other medicines.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Non-prescription sleep aids are frequently purchased by individuals to improve their sleep while delaying seeking medical care.1 Given the product availability and proximity of community pharmacy to the public, the pharmacist has an important role to play in promoting the safe and effective use of non-prescription sleep aids and referring patients to appropriate care.2,3

Non-prescription sleep aids predominantly target insomnia symptoms, utilising their sedative properties to promote faster sleep onset. These are mainly Schedule 3 medicines and include the sedating antihistamines diphenhydramine, promethazine and doxylamine.4 Prolonged-release melatonin may be used as a Schedule 3 medicine in adults ≥55 years of age as a short-term monotherapy for primary insomnia, characterised by poor sleep quality.4

Complementary medicines (CMs; e.g. valerian, passionflower, hops, kava, chamomile) and supplements (e.g. magnesium) are also sometimes used to help aid sleep.5,6 Many of the CMs theoretically act on GABAergic receptors and/or have anxiolytic and relaxant effects.7 The Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook contains further information on various CMs and their reported uses in sleep.6

A key practice dilemma that pharmacists face each day is that despite the widespread availability and use of non-prescription sleep aids, several professional sleep societies recommend against their use due to insufficient evidence.8–10 Therapeutic Guidelines also advises not to use sedating antihistamines to treat insomnia.11 Many of the pivotal trials evaluating first-generation sedating antihistamines and CMs have critical study design limitations that fall short of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) standards that are often used to appraise the evidence base.12

While the evidence bases for both CMs and Schedule 3 sleep aids are unlikely to immediately change, a core practice consideration is the risk-benefit profile of the respective non-prescription sleep aids for the individual patient.

While the evidence bases for both CMs and Schedule 3 sleep aids are unlikely to immediately change, a core practice consideration is the risk-benefit profile of the respective non-prescription sleep aids for the individual patient.

Consumers often misperceive non-prescription sleep aids as being safer than prescription medicines due to their ‘naturalness’ or ease of access.13 As such, these sleep aids are often used medically unsupervised to either initially delay seeking medical care,14 or, in combination with prescribed regimens, to offset the perceived harms of prescription sleep aids.15,16 When non-prescription sleep aids are being used unsupervised, consumers may be unaware of the potential contraindications or interactions with existing medicines. For example, melatonin, while seemingly benign, can have undesired effects in high-risk patient groups. Melatonin can potentially interfere with immunosuppressive therapies,17 and may increase risk of bleeding for patients on anticoagulant medicines such as warfarin.18,19 While many of the interactions with CMs are theoretical, pharmacists play a critical role in assessing risk-benefit and providing advice for the safe use of these non-prescription sleep aids. Nonetheless, discerning the risk profiles of the respective CMs is increasingly challenging since many herbal sleep formulations in the pharmacy combine multiple herbal ingredients.

Patients should be advised to avoid the concomitant use of non-prescription sleep aids with alcohol and medicines that have central nervous system depressing effects, and to avoid driving or operating machinery if drowsy.20 The effects of sleep aids, especially sedating antihistamines, can continue the next day.4,20,21 In addition, non-prescription sleep aids should be limited to short-term use. Sedating antihistamines should not be used for longer than 10 consecutive days because tolerance to their sedative effects develops quickly.4,21,22 In older adults, the risks of using non-prescription sleep aids are even higher. This is because they tend to take more medicines, increasing the potential for drug-drug and drug-herb interactions. In addition, the sedative effects of sedating antihistamines may be more pronounced due to age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes, such as reduced metabolism and clearance.23 Older adults are also more vulnerable to other cognitive and anticholinergic adverse effects of sedating antihistamines, and these medicines can add to the anticholinergic burden.21 Guidelines recommend avoiding the use of sedating antihistamines in older people.⁴ However, older people make up a significant portion of users.23 If it is not possible to avoid use in older people, they should use lower doses than other adults.21

Notwithstanding these acute consequences, one of the main concerns of self-medication is delayed medical help-seeking and initiation of the first-line therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi).24 Individuals may miss the optimal window to address their sleep complaint and allow perpetuating factors such as poor sleep habits and anxiety about the lack of sleep to develop, resulting in the transition of acute insomnia into chronic insomnia (insomnia lasting ≥3 months).8

Is it really insomnia?

Is it really insomnia?From direct product requests to symptom-based requests in the pharmacy, patients will often refer to their sleep complaint as ‘insomnia’ and seek non-prescription sleep aids to improve their sleep. Insomnia symptoms such as difficulty initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, early-morning waking and associated daytime fatigue can appear to overlap with symptoms of other sleep disorders for which non-prescription sleep aids may not be suitable. For example, circadian sleep disorders such as advanced sleep phase disorder and delayed sleep phase disorder share a lot of similarity with insomnia symptoms where the patient experiences difficulty falling asleep at a desired time.25,26 Those with a circadian sleep disorder have an otherwise intact sleep-wake cycle but struggle to fall asleep and wake up at socially acceptable times to meet their daily obligations such as work and school because their internal body clocks have shifted.10 Similarly, for patients with undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), the daytime fatigue and functional impairments often motivates patients to use non-prescription sleep aids to improve their sleep or alertness, but clinical guidelines recommend against their use.27 Another common sleep disorder, restless legs syndrome (RLS), like insomnia, will result in difficulty falling asleep and/or staying asleep with daytime consequences. The disrupted sleep in RLS is largely attributed to the uncomfortable sensation felt in the legs at night when resting and the urge to move and stretch out the legs to relieve discomfort.28 The symptoms of RLS can be precipitated or exacerbated with use of sedating antihistamines.29

Further clinician and patient information on these conditions can be obtained from Sleep Central (www.sleepcentral.org.au), or consumer-facing resources from the Sleep Health Foundation (www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au).

Patients presenting to the pharmacy for non-prescription sleep aids should be assessed for the presence of other sleep disorders.30,31 Pharmacists can probe further into the nature and history of the sleep complaint by asking patients about potential triggers, sleep-wake schedules, engagement in shift work, the presence of other physical symptoms (e.g. snoring or witnessed breathing pauses during sleep, uncomfortable sensations in the lower legs and ability to fall asleep easily at earlier/later times), and prior treatments and response to treatments.3 In addition, there are evidence-based screening and assessment tools for the different sleep disorders that pharmacists may use in their practice to identify at-risk patients for onward referral and assessment by their medical practitioner.

Further information on assessment tools for insomnia and patient education resources can be found on the Sleep Central website (www.sleepcentral.org.au).

Knowledge to practice

Knowledge to practice Despite insufficient evidence supporting the use of non-prescription sleep aids, it is critical to engage patients in a non-judgemental and open discussion about their non-prescription sleep aid use.32 Through these conversations, pharmacists can gain further information about the nature of the patient’s sleep complaint, their current medical and medicines history and treatment expectations. Pharmacists can then educate patients about the various sleep disorders, potential adverse effects and interactions of pharmacological treatment, and inform them about the benefits of seeing a medical practitioner for assessment and optimal treatment.

Non-prescription sleep aids are widely used by members of the community to improve their sleep, but they may not always be an appropriate choice, and risks can often outweigh perceived benefits. Pharmacists play a key role in ensuring non-prescription sleep aids are used safely and effectively. Pharmacists are well placed to direct consumers to evidence-based resources on sleep health and sleep disorders, which may empower them to be better informed about sleep, improve their sleep health literacy, and understand the need for further assessment from a medical practitioner. They can also facilitate onward referral to a medical practitioner for further assessment, differential diagnosis and management of their sleep disturbance.

Case scenario continuedYou ask Amna about her sleep. She wants to go to sleep by 10:30 pm but typically doesn’t feel sleepy until 1 am. Her sleep complaint is only an issue on weekdays when she needs to follow a strict schedule. Weekends are pleasant as she can sleep and wake when she wants. You suggest that Amna may have symptoms of a delayed circadian rhythm rather than insomnia, and refer her to see her GP for a discussion and referral to a sleep specialist. |

Dr Janet Cheung BPharm, MPhil, PhD, FHEA is a pharmacist and Senior Lecturer in Pharmacy Practice at the Sydney Pharmacy School, University of Sydney. Her research broadly focuses on promoting the quality use of sleep medicines through understanding patient medication-taking patterns and behaviours.

Dr Cheung supervises a PhD candidate on a project exploring treatment experiences and needs of self-identified Chinese patients in Australia. The candidate is employed by ResMed Pty Ltd and the company directly funds the research candidate’s research project costs as part of a professional development fund. The funding and nature of the project is not related to this CPD activity.

[post_title] => Non-prescription sleep aids [post_excerpt] => Non-prescription sleep aids are widely used by members of the community to improve their sleep, but they may not always be an appropriate choice, and risks can often outweigh perceived benefits. [post_status] => publish [comment_status] => open [ping_status] => open [post_password] => [post_name] => non-prescription-sleep-aids [to_ping] => [pinged] => [post_modified] => 2025-01-15 09:15:49 [post_modified_gmt] => 2025-01-14 22:15:49 [post_content_filtered] => [post_parent] => 0 [guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28128 [menu_order] => 0 [post_type] => post [post_mime_type] => [comment_count] => 0 [filter] => raw ) [title_attribute] => Non-prescription sleep aids [title] => Non-prescription sleep aids [href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/non-prescription-sleep-aids/ [module_atts:td_module:private] => Array ( ) [td_review:protected] => Array ( [td_post_template] => single_template_4 ) [is_review:protected] => [post_thumb_id:protected] => 28474 [authorType] => )td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28513

[post_author] => 1703

[post_date] => 2025-01-20 13:19:22

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-01-20 02:19:22

[post_content] => With only two weeks before school resumes, now is the ideal time for pharmacists to help parents catch up with vaccinations for their children.

“As a parent of a four and six-year-old child, I know January is typically the time when kids are getting ready for the school year,” said Jacqueline Meyer MPS, owner of LiveLife Pharmacy Cooroy and PSA Queensland Pharmacist of the Year 2023. “Let’s make sure that includes updating vaccinations.”

Ms Meyer said encouraging parents to take advantage of this window of time could help overcome practical difficulties such as a busy lifestyle, while the availability of an increasing number of vaccines at pharmacies was especially helpful in regional areas where it may be more difficult to see a GP.

Research by the National Vaccinations Insight Project found that 23.9% of parents with partially vaccinated children under the age of five did not prioritise their children's vaccination appointments over other things, while 24.8% said it was not easy to get an appointment.

As well as holidays being free of the hustle and bustle of school routine, getting immunised during the holidays means children don’t have to miss a day of school if they have mild vaccination side effects, said Samantha Kourtis, pharmacist and managing partner of Capital Chemist Charnwood in the ACT and the mother of three teenagers.

Overcoming hesitancy

Ms Meyer said it was crucial that pharmacists familiarised themselves with the laws governing vaccinations in different states and territories so they knew what part they could play in boosting immunisation.

In most states and territories pharmacists may administer vaccines to children over the age of five – in Queensland that age is two years and, in Tasmania, in some cases, 10 years.

This can be most helpful for children who have missed out on immunisations through school programs, or from a medical clinic.

Concerningly, however, new research shows vaccination coverage among children in Australia has declined for the third consecutive year.

In 2020, fully vaccinated coverage rates were 94.8% at 12 months, 92.1 at 24 months and 94.8% at five years of age. In 2023 those rates were 92.8, 90.8% and 93.3% respectively.

Between 2020 and 2023, the proportion of children vaccinated within 30 days of the recommended age also decreased for both the second dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP) vaccine (from 90.1% to 83.5% for non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and 80.3% to 74.6% for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children) and the first dose of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine (from 75.3% to 67.2% for non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children children and 64.7% to 56% for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children).

While access issues played some part in the decline, vaccine acceptance or parents’ thoughts and feelings about vaccines and parents’ social influences have also been a factor, according to the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance.

Researchers found 60.2% of parents felt distressed when thinking about vaccinating their children.

Pharmacist Sonia Zhu MPS, of Ramsay Pharmacy Glen Huntly, who has a four year old child, said she often has conversations with parents who feel anxious about vaccination.

“Whenever a parent is concerned, I ask them what is making them feel worried and then I am able to talk to them about the risks of the disease as opposed to the vaccine,” she said.

“I can assure them that vaccinations are just like a practice exam for your immune system and that, if their child gets the disease, they will recover better and more quickly if they are vaccinated.”

Mrs Kourtis said it was also important to reduce vaccination anxiety among children with a friendly healthcare environment, especially for younger children.

“We have regular colouring competitions, fairy doors, fun stickers and a donut stool they sit on to have their vaccination,” she said.

“We also talk to parents about what their child needs before being vaccinated. That may be to wear headphones, for example, or other measures for children who are neurodiverse.”

While Ms Zhu said lollipops were offered to children and teens, Ms Meyer said cartoon images, stuffed toys and devices that acted as distraction tools were other accessories used in pharmacies to help create a calm environment.

The teenage challenge

Vaccine rates in adolescents have also declined. Between 2022 and 2023, coverage decreased for having at least one dose of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine by 15 years of age (from 85.3% to 84.2% for girls and 83.1% to 81.8% for boys); an adolescent dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine by 15 years of age (from 86.9% overall to 85.5%) and one dose of meningococcal ACWY vaccine by 17 years of age (from 75.9% overall to 72.8%).

“We certainly have nowhere near the uptake of meningococcal B vaccine we would like in Queensland,” said Ms Meyer.

According to the Primary Health Network Brisbane South, in the 15 to 20-year-old cohort, just under 14% have been immunised, leaving approximately 386,000 eligible adolescents unvaccinated.

The Queensland MenB Vaccination Program announced this year provides free vaccines to eligible infants, children and adolescents, and is the largest state-funded immunisation program ever implemented in the state.

With pharmacists able to administer all of these vaccinations between year 7 and year 10, Ms Meyer sees a clear opportunity to communicate the benefits of vaccination to parents.

“I think pharmacists could reach out to local schools and offer to conduct educational sessions,” said Ms Meyer. “Community pharmacies often employ teenagers for casual or junior shifts so it may start with simply talking to existing staff that may fit the eligibility criteria for demographic.”

Mrs Kourtis said community pharmacists were well placed to have health promotions in store and on social media.

“They can also try to partner with local community and sporting organisations to promote vaccination through them,” she said.

[post_title] => Boosting childhood vaccination rates in the holidays

[post_excerpt] => With only two weeks before school resumes, now is the ideal time for pharmacists to help parents catch up with vaccinations for their children.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => boosting-childhood-vaccination-rates-in-the-holidays

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-01-20 16:09:35

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-01-20 05:09:35

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28513

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => Boosting childhood vaccination rates in the holidays

[title] => Boosting childhood vaccination rates in the holidays

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/boosting-childhood-vaccination-rates-in-the-holidays/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28514

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28280

[post_author] => 9500

[post_date] => 2025-01-18 08:00:52

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-01-17 21:00:52

[post_content] => Turning informal advice into a structured consultation service: pharmacy-based travel health services take flight.

Australians love to travel and they take off to all parts of the globe, whether it be safaris in Africa, a bargain trip to Bali, visiting family in India or cruising through the icebergs within the Arctic Circle.

But as the average age of travellers, population density, pollution and zoonotic diseases increase, so, too, do health risks associated with travel.

Pharmacists have long provided ad hoc advice for travellers in response to patient queries, whether it be guidance on how to store medicines during transit or encouraging patients to see a GP, or dedicated travel doctor service in major cities, for vaccination.1

But with more Australians jetting off to more locations more frequently, more travel health services are needed. Some pioneering pharmacists are leading the way. Enabled by an increasing range of vaccines pharmacists can both prescribe and administer as well as formal pilots and programs from state governments, community-pharmacy based travel health consultation services are taking flight.

How does a formal travel health service differ from ad hoc advice?

Put simply, its more comprehensive. It considers a much wider range of risks than the patient may self-identify and makes recommendations to the traveller proportional to their individual needs.

‘Outside of a formalised program like the Victorian Community Pharmacy Statewide Pilot project,2 the pharmacist may not go into as much depth about [travel health] matters because there’s an expectation the consumer’s GP will have that discussion when a patient asks about vaccines,’ says PSA Victorian State Manager Jarrod McMaugh MPS.

It means pharmacists ‘instead of picking and choosing pieces of information they’re going to add on to a consultation before referring and saying “go to see your GP for these things”, they’re going to address them all directly in a travel health service’, he says.

And to be comprehensive the service needs a deep understanding of the traveller(s), when/where they are going, how they are going to get there – e.g. cruise, fly, drive, trek – and the types of things they’ll do when they are there.

Getting started

Establishment or formalisation of any service has common features: staff training, developing standard operating procedures, setting up documentation systems and advertising. However, a travel health service has two additional aspects, which are critical to success.

Firstly, the practitioners need to really wrap their heads around international travel, the health risks a person is likely to encounter and how to craft a valuable consultation for each traveller.

‘Some pharmacists are avid international travellers, and will have generated substantial knowledge of destinations, transport routes and product availability at pharmacies overseas. This expertise is advantageous in providing bespoke, individualised advice,’ Mr McMaugh says.

‘For example, Australians are often surprised by the high cost of sunscreens overseas, or how unpleasant the taste of oral rehydration products available in other markets are.’

‘Additionally, people often overlook prohibitions on carrying common medicines through common transit points such as Middle Eastern or Asian airport hubs.’

These kinds of insights may not be front-of-mind for travellers when booking in for a consultation, but they are important for risk mitigation and highly valued.

Also important is anticipating risks for which travellers may not be alert. For example, a family holiday to a Thailand beach resort may initially seem lower risk, but activities and excursions where you interact with wildlife such as monkeys are common and carry zoonotic infection risk.

For pharmacists who do not have this knowledge from primary experience, seeking these reflections from colleagues or through careful listening with patients is essential.

For pharmacists who do not have this knowledge from primary experience, seeking these reflections from colleagues or through careful listening with patients is essential.

Structuring a consultation is something each practitioner needs to find their own way to master. Unlike other services, the approach to these longer consultations isn’t so black and white.

Compared to other expanded scope programs, travel health requires mastering the navigation of the grey.

One of the hundreds of pharmacists offering a travel service under the Victorian pilot is Melbourne’s Tooronga Amcal Pharmacy owner Andrew Robinson MPS, who reflected that ‘[with a UTI treatment service], we follow a protocol guideline and it’s more straightforward to undertake’. With travel, it is like a Pandora’s box that you can open and find you going all over the place with a whole lot of different destinations, a whole lot of different complications, a lot of different needs.’

Finding prospective travellers

A common theme with all pharmacists contacted by AP is that the identification of patients who would benefit from the service has initially been more successful through conversations in patient interactions than via formal advertising.

The trigger for knowing a patient could benefit from a sit-down travel health consultation with a pharmacist could be anything, Mr McMaugh notes.

‘It can literally be a comment in passing: ‘My son is about to travel overseas for the first time.’

Other queries could be related to how to carry medicines safely overseas, or interest in medicines for motion sickness.

Andrew Robinson describes the trial as a ‘significant endorsement by health regulators that pharmacists are capable of delivering more complex services.

‘Before actually doing an appointment, you’ve got to tease it out a bit first. It’s not like some of the other pilot programs that we’ve done, which are very, “you’ve got a urinary tract infection. You fit the criteria. We can undertake the consultation”.’

‘In contrast, you almost need to do a [travel health] consultation to find out whether you need to refer them on. So, I try and garner that before. But I think if we boil it down and keep it simple, the reality is there’s plenty of people out there who are not thinking about travel health that need a typhoid vaccine and a bit of a conversation,’ he said.

Mr Robinson identified that consumers who, at short notice, book a trip to south-east Asia and don’t plan a GP visit have particularly welcomed his travel health consultations.

Mr Robinson identified that consumers who, at short notice, book a trip to south-east Asia and don’t plan a GP visit have particularly welcomed his travel health consultations.

‘We see this particular pilot really looking at the high-risk patient, the person who sees a cheap flight to Indonesia and in 3 weeks’ time they’re gone. They think of it as just a great way to relax and give very little thought to the risks associated with that travel.’

Susannah Clavin MPS, the owner of the Marc Clavin Pharmacy at Sorrento on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula, regularly discusses travel health with patients and consumers, and has had success with online bookings.

‘Most [patients] were heading to south-east-Asia. They are all very time-poor, so if the pharmacy is closely located to their home or workplace then I think they will appreciate the convenience. Being able to book online, too, is a bonus.’

Like Mr Robinson, Ms Clavin had also identified patients through conversations at the dispensary.

‘One of the patients had a prescription for the vaccine and asked us for a quote,’ recalls Ms Clavin. ‘We gave the quote and mentioned that we could also administer the vaccine, for a fee. [The patient] was very keen to save a trip to the doctor.’

Fee-for-service

How much should the service charge? While each business needs to make its own decision based on the costs of delivery and business policies, experience in travel doctor clinics and within pilot sites shows consumers are willing to pay for the consultation service, which may include administration of vaccines.

When AP spoke to Mr Robinson, he had conducted about a dozen travel health consultations, charging $50 for a half-hour consultation. Families travelling overseas, he says, have found the consultations particularly attractive because the pharmacist can give advice to an entire family in one appointment.

Looking to the future

Feedback from the Victorian trial shows an effective travel health consultation service is a good fit with pharmacies that have a well-integrated vaccination service, according to Mr McMaugh.

‘If you’re doing the occasional vaccine, you have to change gears, going from doing whatever other services or dispensing you were doing, to administering the vaccine and then coming back into the retail and dispensing space,’ he says.

Mr Robinson hopes travel health consultations become a permanent fixture in the service landscape for pharmacy.

‘Travel is all about having fun. But we need to make sure it stays fun, and you stay healthy, because otherwise it’s a very expensive holiday.’

The rise of zoonotic diseases

The rise of zoonotic diseases

Where a person is travelling to and where they are staying matters. A trip to Zimbabwe to see Victoria Falls has a very different risk profile to a walking safari at remote campsites. Similarly, holiday resorts in south-east Asia next to agricultural fields have a different risk profile to city hotels.

Recent decades have seen the rise and reemergence of viral zoonotic diseases.4 The growth of tourism has led to land changes, travel patterns and farming practices which increase the risk of zoonotic diseases, including novel and well-established pathogens.⁵

Travellers and health professionals alike need to keep abreast of these trends. Rabies is a good case in point. The USA continues to log around 4,000 animal rabies cases each year, with >90% of cases from bats, raccoons, skunks and foxes – a shift from the 1960s where dogs were the primary rabies risk to humans.⁶ In contrast, dog bites are the predominant source of rabies infections in Africa.⁷

Karen Carter FPS, partner of Carter’s Pharmacy Gunnedah and owner of Narrabri Pharmacy in north-west NSW, can now offer rabies vaccinations.

‘You think of exotic animals for rabies but sometimes it’s dogs that people are at risk of being bitten by,’ Ms Carter says.

The vaccine isn’t cheap, so considering the exposure risk and access to post-exposure prophylaxis is important when discussing the benefits of the vaccine with patients.

‘We had a gentleman travelling to Africa and then on to South America for his work in the agriculture industry, so we recommended he get the rabies vaccine.’ Ms Carter says. In fact, he not only got the rabies vaccine administered, but the hepatitis A and typhoid vaccines as well before he left.

‘We were also able to refer him to a Tamworth GP clinic for his yellow fever vaccines, Ms Carter adds. ‘He thought it was great that we could do all but one of his vaccines in the pharmacy.’

Other zoonotic infections, such as mpox, avian influenza and Japanese encephalitis also have changing patterns of transmission and distribution, which increasingly require consideration in travel health services.

Case study

Dat Le MPS Owner, Priceline Pharmacy, Knox, Melbourne VIC

Dat Le MPS Owner, Priceline Pharmacy, Knox, Melbourne VIC

This traveller

Mrs L, a 62-year-old regular dose administration aid (DAA) patient, is living with gastro-oesophogeal reflux disease (GORD), hypertension, atrial fibrillation, high cholesterol and osteoarthritis in the knee.

Current medicines

This time Mrs L explains that it will be summer when she arrives in both south-east Asian countries.

Recommendations

Based on her travel plans, I recommend vaccination for:

Mrs L was advised she would have full protection from hepatitis A in 2 weeks and that it may be at least a week before the COVID-19 booster provided full protection.

She was also told that the vaccinations may cause sore arms, some redness, fever or chills.

While her typhoid vaccination would protect her for 3 years, she could have another COVID-19 booster in a year.

For the hepatitis A vaccine, a typical course is two doses – the first at day 0, and the second from 6 months later, ideally before 12 months, if she travels again within the year.

Rehydration preparations were also recommended, along with hand sanitiser, face masks and sunscreen for Mrs L’s holiday group tour to various sight-seeing locations.

When she collected her DAAs, we advised Mrs L how to store her medicines. She was pleased she didn’t need to make a GP appointment, organise vaccine prescriptions, collect them at the pharmacy and then take them back to the doctor to be administered. I reminded her that we would call her about her second hepatitis A dose to complete her course.

We put a note on her next DAA collection asking about her holiday and any problems she may have had such as diarrhoea or tablet storage problems.

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28126

[post_author] => 9499

[post_date] => 2025-01-17 08:00:19

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-01-16 21:00:19

[post_content] => Case scenario

Mrs Johnson, a 65-year-old patient with hypertension, comes to the pharmacy to fill her repeat prescriptions for perindopril 4 mg and amlodipine 5 mg. You notice that Mrs Johnson is getting her repeats dispensed irregularly and offer her a blood pressure (BP) check. Mrs Johnson mentions that her BP has been poorly controlled, and she often forgets to take her medicines.

Learning objectivesAfter reading this article, pharmacists should be able to:

|

Already read the CPD in the journal? Scroll to the bottom to SUBMIT ANSWERS.

Missed or delayed administration of prescribed doses is a common concern in clinical practice and can be viewed under the framework of non-adherence, either intentional or unintentional. Medication adherence refers to the extent to which a person’s behaviour matches with the agreed recommendations from a health care provider.1 Adherence to prescribed dosing regimens is crucial for achieving the best therapeutic outcome.

Understanding the implications of missed doses and how to manage them effectively will assist pharmacists in providing clear and concise instructions to patients who miss a dose.