td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28898

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-12 14:26:24

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-12 03:26:24

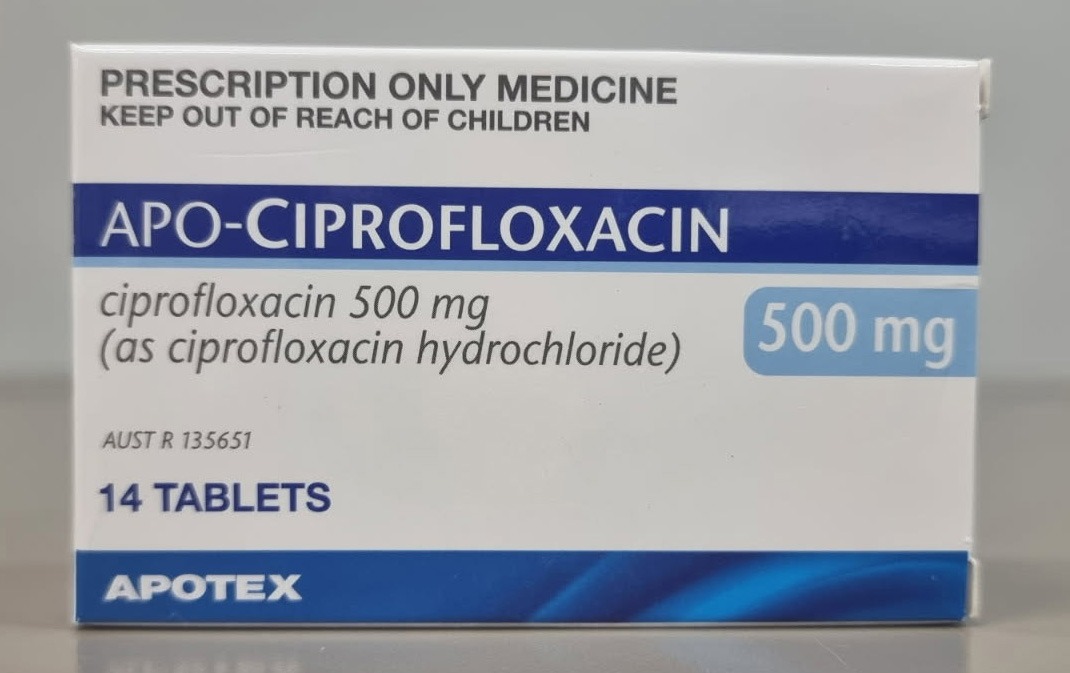

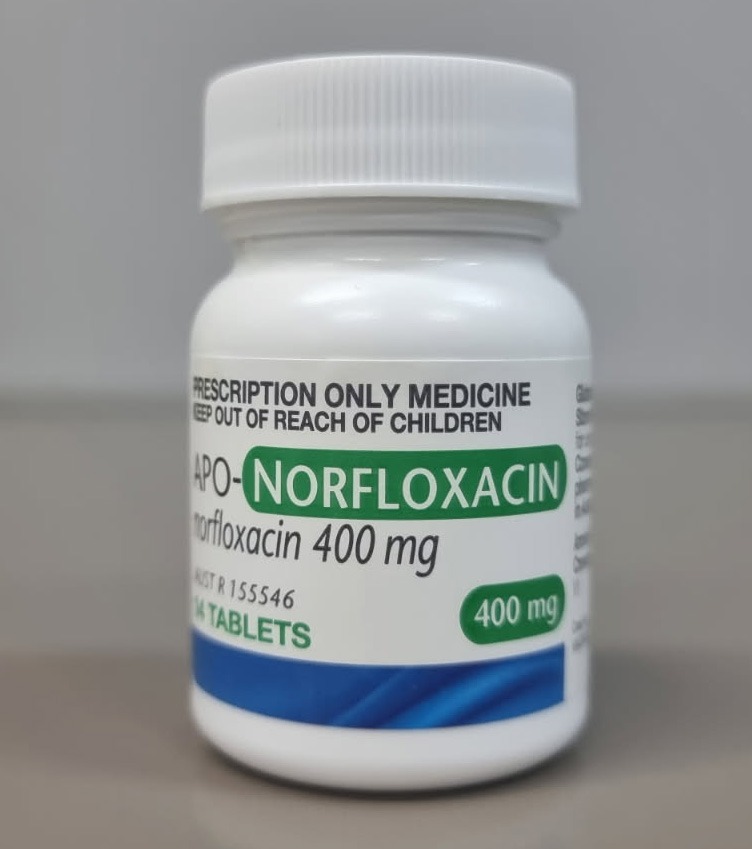

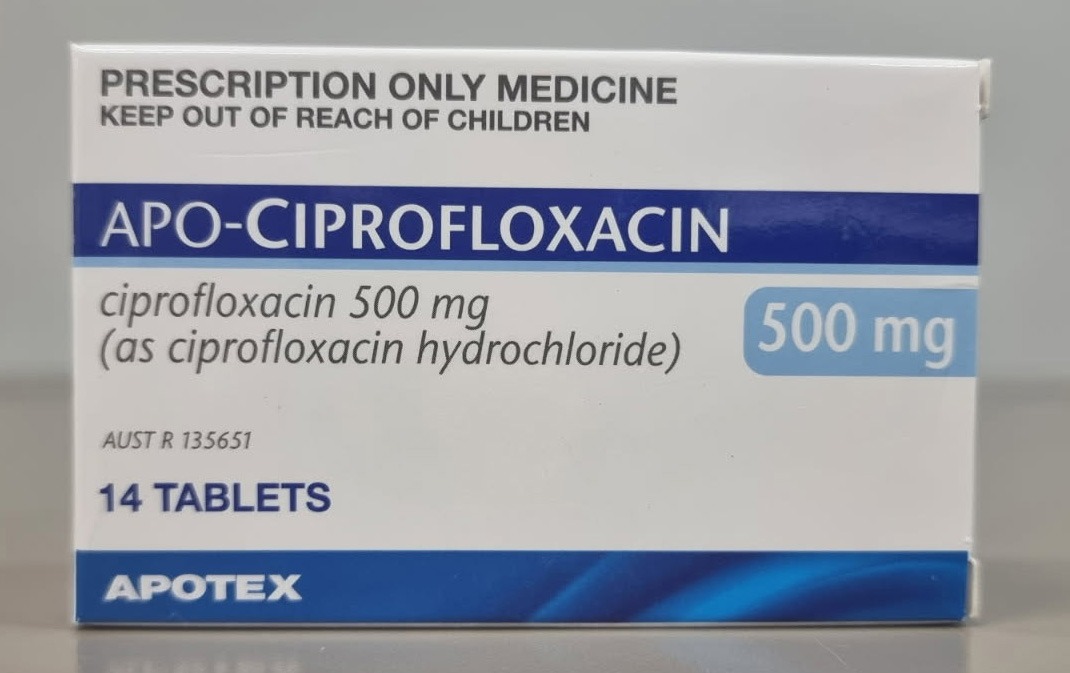

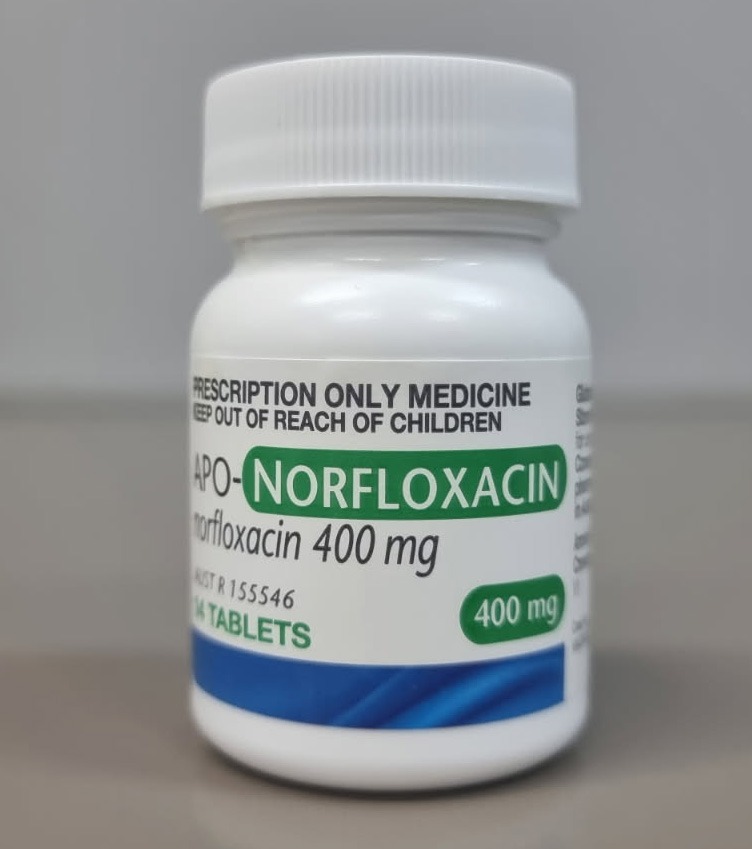

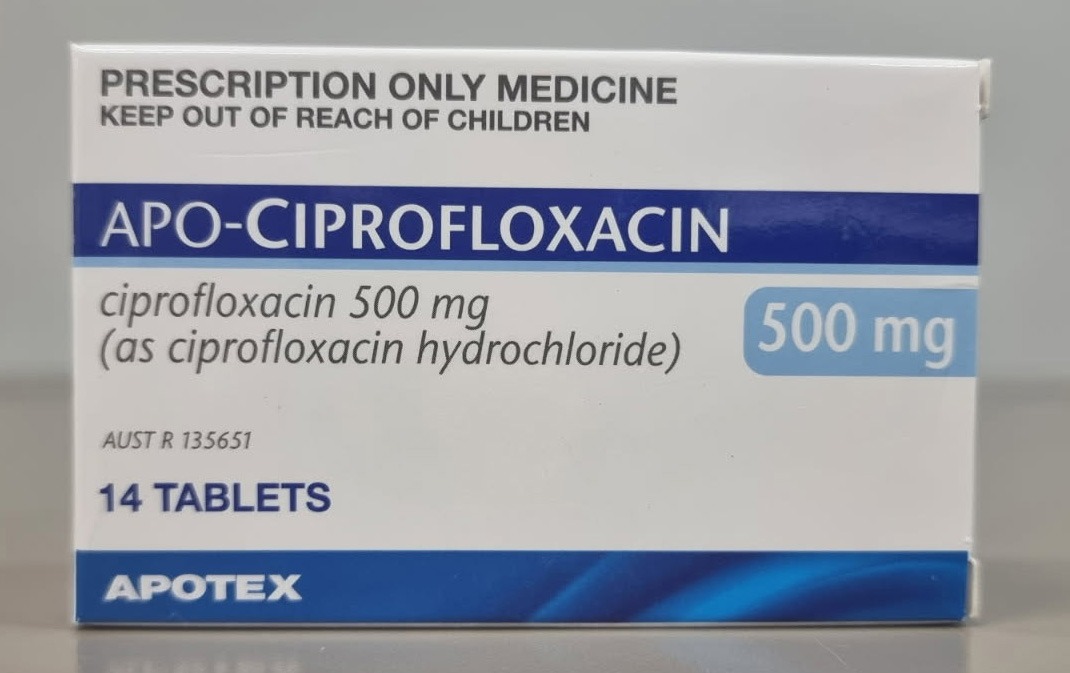

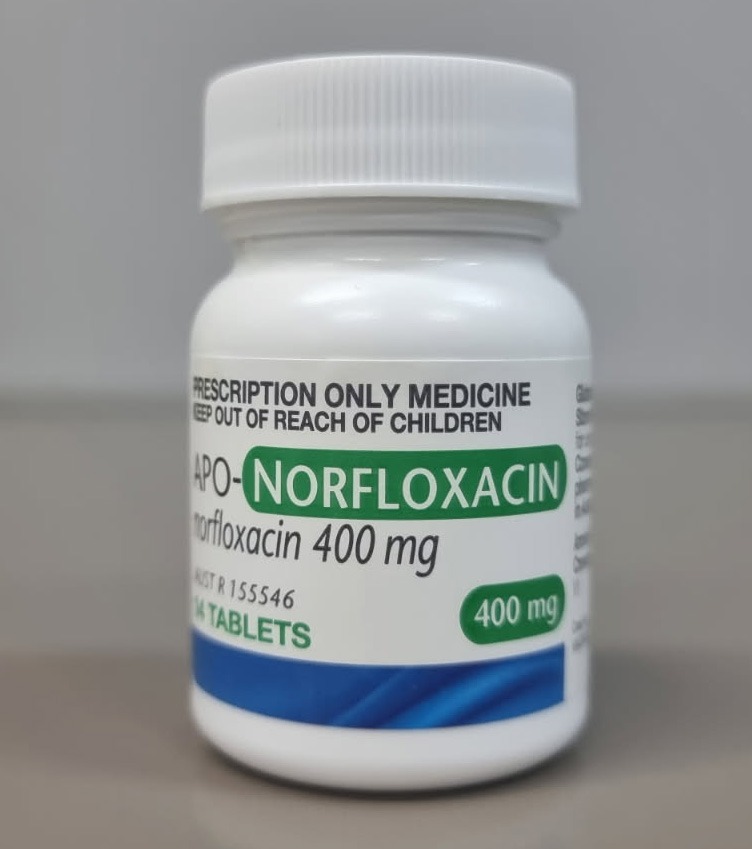

[post_content] => The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) issued an alert over the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used to treat infections such as urinary tract, respiratory and gastrointestinal infections.

What class of antibiotics prompted the alert?

Antimicrobials from the broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and moxifloxacin. This includes all oral and injectable forms of fluoroquinolones.

What are the documented adverse effects?

Central nervous system (CNS) and psychiatric events. Although rare, the complications are serious – and are potentially disabling and irreversible.

Adverse events include:

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28879

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 11:31:17

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-10 00:31:17

[post_content] => From guiding older patients on National Immunisation Program (NIP) stock to clarifying second-dose rules, here’s what pharmacists need to know about the 2025 influenza season.

1. Patients aged 65 years and older should wait for NIP stock to arrive

By this time of the year, most pharmacies will have ordered and received private stock of influenza vaccines. But for the 2025 season, deliveries of NIP are expected to commence around late March, following the confirmation of pre-allocated orders by pharmacies.

Older patients who present to the pharmacy requesting an influenza vaccine should be advised to wait until NIP stock arrives for optimum protection.

Patients who are 65 years and over should receive the NIP-funded Fluad Quad

0.50 mL vaccine or Fluzone High-Dose Quadrivalent, adjuvanted quadrivalent vaccines designed to boost the immune system's response to the vaccine.

These vaccines help to generate a stronger and more sustained antibody response, providing better protection against influenza and its complications in this vulnerable age cohort – reducing hospitalisations and severe outcomes from influenza.

2. Patients (mostly) only need one dose of an influenza vaccine

If a patient received an influenza vaccine earlier on in the season and is concerned about waning immunity – one vaccine is still enough. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to justify routinely administering a second influenza vaccine dose within the same season.

Optimal protection from the influenza vaccine persists for around 3–4 months after vaccination. While the vaccine’s effectiveness begins to wane after this point, most patients should be sufficiently protected throughout the season.

However, there are some exceptions. Patients eligible for a second dose include:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28864

[post_author] => 9832

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 10:32:16

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-09 23:32:16

[post_content] => Family and friend carers are essential members of the care team who often provide invaluable medication management support to the people they care for.

[caption id="attachment_28875" align="alignright" width="300"] This article was sponsored and developed in collaboration with PSA and Carers NSW[/caption]

However, pharmacists may perceive medication errors or non-adherence as a carer’s inability to fulfil this role,1 instead of an opportunity for improving education and support. Ensuring that carers are identified by pharmacists as members of the patient’s care team, included in discussions about the patient’s care and supported to fulfil their role is key to ensuring quality use of medicines and optimal outcomes for patients and carers.

Across Australia, there are approximately 3 million carers who provide unpaid care or support to a family member or friend living with disability, mental illness, chronic or life-limiting illness, drug or alcohol dependency or who is ageing or frail.2 This includes at least 391,300 children and young people under 25 years of age.2 A carer may be a parent, partner, sibling, relative, child, friend or neighbour of the person requiring care. Carers come from all walks of life, and anyone can become a carer at any time.

Carers are diverse and each caring experience is different. Carers provide a wide range of supports to help the person they care for to remain living at home and in the community. They may also provide ongoing support for someone living temporarily or permanently in residential care. This support can include personal care, domestic assistance, support with navigating and coordinating health and disability services, emotional and social support, as well as assistance with communication, decision making and advocacy.3

Pharmacies are a common setting that carers visit with, or on behalf of, the person they care for. Carers may support with:

This article was sponsored and developed in collaboration with PSA and Carers NSW[/caption]

However, pharmacists may perceive medication errors or non-adherence as a carer’s inability to fulfil this role,1 instead of an opportunity for improving education and support. Ensuring that carers are identified by pharmacists as members of the patient’s care team, included in discussions about the patient’s care and supported to fulfil their role is key to ensuring quality use of medicines and optimal outcomes for patients and carers.

Across Australia, there are approximately 3 million carers who provide unpaid care or support to a family member or friend living with disability, mental illness, chronic or life-limiting illness, drug or alcohol dependency or who is ageing or frail.2 This includes at least 391,300 children and young people under 25 years of age.2 A carer may be a parent, partner, sibling, relative, child, friend or neighbour of the person requiring care. Carers come from all walks of life, and anyone can become a carer at any time.

Carers are diverse and each caring experience is different. Carers provide a wide range of supports to help the person they care for to remain living at home and in the community. They may also provide ongoing support for someone living temporarily or permanently in residential care. This support can include personal care, domestic assistance, support with navigating and coordinating health and disability services, emotional and social support, as well as assistance with communication, decision making and advocacy.3

Pharmacies are a common setting that carers visit with, or on behalf of, the person they care for. Carers may support with:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28858

[post_author] => 7616

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 09:21:35

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-09 22:21:35

[post_content] => Food can act as a prompt for medicine administration and be an easy way for patients to incorporate doses into their routines.

Explaining to patients that they should take a medicine on an empty stomach or in a specific way away from food may not always be met with great enthusiasm! Confusion, and not fitting into a patient’s routine where possible, can lead to poor adherence and negative patient outcomes.

Why does food sometimes matter?

Food, or the absence of it, may significantly impact systemic exposure, safety, tolerability and effectiveness of a medicine, depending on its pharmacokinetics and adverse effects.

Take alendronate for example – the product information (PI) recommends taking it at least 30 minutes before the first food of the day as its bioavailability is negligible when taken with or up to 2 hours after a meal.1,2

Why do some PIs have a differing definition of an ‘empty stomach’?

This may stem from Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance in America, where many medicines are first introduced to the market.

FDA guidance for medicine sponsors suggests that if a medicine needs to be taken in fasted conditions, studies using an overnight fast of at least 10 hours before medicine administration, and waiting at least 4 hours after the dose before eating, are optimal. However, this might not be practical for all medicines and patients. It is then up to the medicine’s sponsor to provide pharmacokinetic data to support pragmatic and realistic dosing instructions for patients to separate food and medicine administration. Sponsors can use modified fasting conditions with differing separation times, and must consider frequency of medicine dosing, the likely demographics of the patient, the condition being treated and any other relevant factors.3 These could vary significantly between different medicines!

Why does CAL 3b say something different to the PI?

The Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook (APF) considers that an empty stomach for the purposes of medicine absorption is ‘at least half an hour before food or two hours after food’, as reflected in the wording of Cautionary Advisory Label (CAL) 3b.4,5

This standardised approach is to ensure medicine instructions are simplified and practical for patients, and may differ from the medicine’s PI. Remember, CALs are intended to be used as an adjunct, not a replacement, to verbal counselling.5

Consider adherence and use professional judgement when providing advice on dose administration.

This may require weighing up optimal dose timing and adherence if a patient can’t easily accommodate the timing of doses, particularly when treating chronic conditions.4

References

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Fosamax Plus Product Information. 2024. At: www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/136846

- Alendronate. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference; [updated 30 Oct 2024]. At: www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/martindale/22524-r?hspl=alendronate#content%2Fmartindale%2F22524-r%2319721-a3-v

- US Food and Drug Administration. Assessing the effects of food on drugs in INDs and NDAs – clinical pharmacology considerations: guidance for industry. 2022. At: www.fda.gov/media/121313/download

- Grannell, L. When should I take my medicines? Aust Prescr 2019;42:86–9.

- Sansom LN, ed. Cautionary advisory labels Explanatory notes. Australian pharmaceutical formulary and handbook; [updated 2024 Jul 24]. At: https://apf.psa.org.au/dispensing-and-labelling/cautionary-advisory-labels/explanatory-notes

[post_title] => What is an empty stomach?

[post_excerpt] => Confusion around what's meant by an empty stomach can lead to poor adherence. Here's how clear instructions can make a world of difference.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => what-is-an-empty-stomach

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-03-10 09:24:03

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-09 22:24:03

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28858

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => What is an empty stomach?

[title] => What is an empty stomach?

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/what-is-an-empty-stomach/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28860

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28830

[post_author] => 8304

[post_date] => 2025-03-05 12:47:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-05 01:47:11

[post_content] => Rosuvastatin. Pantoprazole. Perindopril. Sertraline. These were some of the most commonly prescribed PBS drugs in 2024. But what else do they have in common?

Tongue-twisters aside, they’re all examples of judiciously crafted drug names that have gone through countless rounds of testing by researchers, developers and brand marketing teams before making their way into Australian pharmacies.

Pharmacists are trained to interpret the class of drugs from the last few letters of a generic name, particularly after Australia transitioned to active ingredient prescribing in 2021. But how do we get from sertraline to Zoloft, and what about the many forms of ethinylestradiol-based birth contraceptives (Yaz, Jolessa… Sronyx)? As it turns out, drug naming is more complex than it seems.

Australian Pharmacist looks at the hard and fast rules governing drug monikers – all designed with patient safety in mind.

Breaking down a drug name

Pharmacists are likely well aware of the multiple guises medications take – three in fact: their chemical name, generic name (or nonproprietary), and brand name.

The chemical name follows rules set by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

Once the drug is approved by the relevant regulator, it’s then assigned a generic and brand name. The generic name is based on the active ingredient and follows a standardised nomenclature, while the brand name is the trademarked name proposed by the manufacturer.

It’s within these last two categories that drug developers have a bit of scope for creativity.

The science behind generic names

Before paracetamol lands in the pharmacy aisle as Panadol, pharmaceutical companies must first propose a generic name for the medication.

This name must be greenlit by two organisations: the national regulating body (i.e. in Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Association), and on a global stage, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Nonproprietary Name (INN) Programme.

Generic names follow an internationally recognised formula of prefix–infix–stem to maintain consistency regardless of where someone is located, and minimise the risk of prescribing errors. The:

| Stem | Uses | Examples |

| -cillin | Antibiotics (penicillin type) | Amoxicillin, ampicillin, |

| -mab | Monoclonal antibodies used for cancer, autoimmune diseases and other conditions | Adalimumab, abciximab, trastuzumab |

| -profen | Anti-inflammatories (ibuprofen type) | Ibuprofen, flurbiprofen |

| -vastatin | HMG-CoA inhibitors, lowers cholesterol | Atorvastatin, lovastatin, rosuvastatin |

| -vir | Anti-viral drugs (to treat HIV, herpes, hepatitis) | Aciclovir, ritonavir |

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28898

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-12 14:26:24

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-12 03:26:24

[post_content] => The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) issued an alert over the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used to treat infections such as urinary tract, respiratory and gastrointestinal infections.

What class of antibiotics prompted the alert?

Antimicrobials from the broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and moxifloxacin. This includes all oral and injectable forms of fluoroquinolones.

What are the documented adverse effects?

Central nervous system (CNS) and psychiatric events. Although rare, the complications are serious – and are potentially disabling and irreversible.

Adverse events include:

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28879

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 11:31:17

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-10 00:31:17

[post_content] => From guiding older patients on National Immunisation Program (NIP) stock to clarifying second-dose rules, here’s what pharmacists need to know about the 2025 influenza season.

1. Patients aged 65 years and older should wait for NIP stock to arrive

By this time of the year, most pharmacies will have ordered and received private stock of influenza vaccines. But for the 2025 season, deliveries of NIP are expected to commence around late March, following the confirmation of pre-allocated orders by pharmacies.

Older patients who present to the pharmacy requesting an influenza vaccine should be advised to wait until NIP stock arrives for optimum protection.

Patients who are 65 years and over should receive the NIP-funded Fluad Quad

0.50 mL vaccine or Fluzone High-Dose Quadrivalent, adjuvanted quadrivalent vaccines designed to boost the immune system's response to the vaccine.

These vaccines help to generate a stronger and more sustained antibody response, providing better protection against influenza and its complications in this vulnerable age cohort – reducing hospitalisations and severe outcomes from influenza.

2. Patients (mostly) only need one dose of an influenza vaccine

If a patient received an influenza vaccine earlier on in the season and is concerned about waning immunity – one vaccine is still enough. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to justify routinely administering a second influenza vaccine dose within the same season.

Optimal protection from the influenza vaccine persists for around 3–4 months after vaccination. While the vaccine’s effectiveness begins to wane after this point, most patients should be sufficiently protected throughout the season.

However, there are some exceptions. Patients eligible for a second dose include:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28864

[post_author] => 9832

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 10:32:16

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-09 23:32:16

[post_content] => Family and friend carers are essential members of the care team who often provide invaluable medication management support to the people they care for.

[caption id="attachment_28875" align="alignright" width="300"] This article was sponsored and developed in collaboration with PSA and Carers NSW[/caption]

However, pharmacists may perceive medication errors or non-adherence as a carer’s inability to fulfil this role,1 instead of an opportunity for improving education and support. Ensuring that carers are identified by pharmacists as members of the patient’s care team, included in discussions about the patient’s care and supported to fulfil their role is key to ensuring quality use of medicines and optimal outcomes for patients and carers.

Across Australia, there are approximately 3 million carers who provide unpaid care or support to a family member or friend living with disability, mental illness, chronic or life-limiting illness, drug or alcohol dependency or who is ageing or frail.2 This includes at least 391,300 children and young people under 25 years of age.2 A carer may be a parent, partner, sibling, relative, child, friend or neighbour of the person requiring care. Carers come from all walks of life, and anyone can become a carer at any time.

Carers are diverse and each caring experience is different. Carers provide a wide range of supports to help the person they care for to remain living at home and in the community. They may also provide ongoing support for someone living temporarily or permanently in residential care. This support can include personal care, domestic assistance, support with navigating and coordinating health and disability services, emotional and social support, as well as assistance with communication, decision making and advocacy.3

Pharmacies are a common setting that carers visit with, or on behalf of, the person they care for. Carers may support with:

This article was sponsored and developed in collaboration with PSA and Carers NSW[/caption]

However, pharmacists may perceive medication errors or non-adherence as a carer’s inability to fulfil this role,1 instead of an opportunity for improving education and support. Ensuring that carers are identified by pharmacists as members of the patient’s care team, included in discussions about the patient’s care and supported to fulfil their role is key to ensuring quality use of medicines and optimal outcomes for patients and carers.

Across Australia, there are approximately 3 million carers who provide unpaid care or support to a family member or friend living with disability, mental illness, chronic or life-limiting illness, drug or alcohol dependency or who is ageing or frail.2 This includes at least 391,300 children and young people under 25 years of age.2 A carer may be a parent, partner, sibling, relative, child, friend or neighbour of the person requiring care. Carers come from all walks of life, and anyone can become a carer at any time.

Carers are diverse and each caring experience is different. Carers provide a wide range of supports to help the person they care for to remain living at home and in the community. They may also provide ongoing support for someone living temporarily or permanently in residential care. This support can include personal care, domestic assistance, support with navigating and coordinating health and disability services, emotional and social support, as well as assistance with communication, decision making and advocacy.3

Pharmacies are a common setting that carers visit with, or on behalf of, the person they care for. Carers may support with:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28858

[post_author] => 7616

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 09:21:35

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-09 22:21:35

[post_content] => Food can act as a prompt for medicine administration and be an easy way for patients to incorporate doses into their routines.

Explaining to patients that they should take a medicine on an empty stomach or in a specific way away from food may not always be met with great enthusiasm! Confusion, and not fitting into a patient’s routine where possible, can lead to poor adherence and negative patient outcomes.

Why does food sometimes matter?

Food, or the absence of it, may significantly impact systemic exposure, safety, tolerability and effectiveness of a medicine, depending on its pharmacokinetics and adverse effects.

Take alendronate for example – the product information (PI) recommends taking it at least 30 minutes before the first food of the day as its bioavailability is negligible when taken with or up to 2 hours after a meal.1,2

Why do some PIs have a differing definition of an ‘empty stomach’?

This may stem from Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance in America, where many medicines are first introduced to the market.

FDA guidance for medicine sponsors suggests that if a medicine needs to be taken in fasted conditions, studies using an overnight fast of at least 10 hours before medicine administration, and waiting at least 4 hours after the dose before eating, are optimal. However, this might not be practical for all medicines and patients. It is then up to the medicine’s sponsor to provide pharmacokinetic data to support pragmatic and realistic dosing instructions for patients to separate food and medicine administration. Sponsors can use modified fasting conditions with differing separation times, and must consider frequency of medicine dosing, the likely demographics of the patient, the condition being treated and any other relevant factors.3 These could vary significantly between different medicines!

Why does CAL 3b say something different to the PI?

The Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook (APF) considers that an empty stomach for the purposes of medicine absorption is ‘at least half an hour before food or two hours after food’, as reflected in the wording of Cautionary Advisory Label (CAL) 3b.4,5

This standardised approach is to ensure medicine instructions are simplified and practical for patients, and may differ from the medicine’s PI. Remember, CALs are intended to be used as an adjunct, not a replacement, to verbal counselling.5

Consider adherence and use professional judgement when providing advice on dose administration.

This may require weighing up optimal dose timing and adherence if a patient can’t easily accommodate the timing of doses, particularly when treating chronic conditions.4

References

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Fosamax Plus Product Information. 2024. At: www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/136846

- Alendronate. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference; [updated 30 Oct 2024]. At: www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/martindale/22524-r?hspl=alendronate#content%2Fmartindale%2F22524-r%2319721-a3-v

- US Food and Drug Administration. Assessing the effects of food on drugs in INDs and NDAs – clinical pharmacology considerations: guidance for industry. 2022. At: www.fda.gov/media/121313/download

- Grannell, L. When should I take my medicines? Aust Prescr 2019;42:86–9.

- Sansom LN, ed. Cautionary advisory labels Explanatory notes. Australian pharmaceutical formulary and handbook; [updated 2024 Jul 24]. At: https://apf.psa.org.au/dispensing-and-labelling/cautionary-advisory-labels/explanatory-notes

[post_title] => What is an empty stomach?

[post_excerpt] => Confusion around what's meant by an empty stomach can lead to poor adherence. Here's how clear instructions can make a world of difference.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => what-is-an-empty-stomach

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-03-10 09:24:03

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-09 22:24:03

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28858

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => What is an empty stomach?

[title] => What is an empty stomach?

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/what-is-an-empty-stomach/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28860

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28830

[post_author] => 8304

[post_date] => 2025-03-05 12:47:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-05 01:47:11

[post_content] => Rosuvastatin. Pantoprazole. Perindopril. Sertraline. These were some of the most commonly prescribed PBS drugs in 2024. But what else do they have in common?

Tongue-twisters aside, they’re all examples of judiciously crafted drug names that have gone through countless rounds of testing by researchers, developers and brand marketing teams before making their way into Australian pharmacies.

Pharmacists are trained to interpret the class of drugs from the last few letters of a generic name, particularly after Australia transitioned to active ingredient prescribing in 2021. But how do we get from sertraline to Zoloft, and what about the many forms of ethinylestradiol-based birth contraceptives (Yaz, Jolessa… Sronyx)? As it turns out, drug naming is more complex than it seems.

Australian Pharmacist looks at the hard and fast rules governing drug monikers – all designed with patient safety in mind.

Breaking down a drug name

Pharmacists are likely well aware of the multiple guises medications take – three in fact: their chemical name, generic name (or nonproprietary), and brand name.

The chemical name follows rules set by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

Once the drug is approved by the relevant regulator, it’s then assigned a generic and brand name. The generic name is based on the active ingredient and follows a standardised nomenclature, while the brand name is the trademarked name proposed by the manufacturer.

It’s within these last two categories that drug developers have a bit of scope for creativity.

The science behind generic names

Before paracetamol lands in the pharmacy aisle as Panadol, pharmaceutical companies must first propose a generic name for the medication.

This name must be greenlit by two organisations: the national regulating body (i.e. in Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Association), and on a global stage, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Nonproprietary Name (INN) Programme.

Generic names follow an internationally recognised formula of prefix–infix–stem to maintain consistency regardless of where someone is located, and minimise the risk of prescribing errors. The:

| Stem | Uses | Examples |

| -cillin | Antibiotics (penicillin type) | Amoxicillin, ampicillin, |

| -mab | Monoclonal antibodies used for cancer, autoimmune diseases and other conditions | Adalimumab, abciximab, trastuzumab |

| -profen | Anti-inflammatories (ibuprofen type) | Ibuprofen, flurbiprofen |

| -vastatin | HMG-CoA inhibitors, lowers cholesterol | Atorvastatin, lovastatin, rosuvastatin |

| -vir | Anti-viral drugs (to treat HIV, herpes, hepatitis) | Aciclovir, ritonavir |

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28898

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-12 14:26:24

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-12 03:26:24

[post_content] => The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) issued an alert over the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used to treat infections such as urinary tract, respiratory and gastrointestinal infections.

What class of antibiotics prompted the alert?

Antimicrobials from the broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and moxifloxacin. This includes all oral and injectable forms of fluoroquinolones.

What are the documented adverse effects?

Central nervous system (CNS) and psychiatric events. Although rare, the complications are serious – and are potentially disabling and irreversible.

Adverse events include:

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28879

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 11:31:17

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-10 00:31:17

[post_content] => From guiding older patients on National Immunisation Program (NIP) stock to clarifying second-dose rules, here’s what pharmacists need to know about the 2025 influenza season.

1. Patients aged 65 years and older should wait for NIP stock to arrive

By this time of the year, most pharmacies will have ordered and received private stock of influenza vaccines. But for the 2025 season, deliveries of NIP are expected to commence around late March, following the confirmation of pre-allocated orders by pharmacies.

Older patients who present to the pharmacy requesting an influenza vaccine should be advised to wait until NIP stock arrives for optimum protection.

Patients who are 65 years and over should receive the NIP-funded Fluad Quad

0.50 mL vaccine or Fluzone High-Dose Quadrivalent, adjuvanted quadrivalent vaccines designed to boost the immune system's response to the vaccine.

These vaccines help to generate a stronger and more sustained antibody response, providing better protection against influenza and its complications in this vulnerable age cohort – reducing hospitalisations and severe outcomes from influenza.

2. Patients (mostly) only need one dose of an influenza vaccine

If a patient received an influenza vaccine earlier on in the season and is concerned about waning immunity – one vaccine is still enough. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to justify routinely administering a second influenza vaccine dose within the same season.

Optimal protection from the influenza vaccine persists for around 3–4 months after vaccination. While the vaccine’s effectiveness begins to wane after this point, most patients should be sufficiently protected throughout the season.

However, there are some exceptions. Patients eligible for a second dose include:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28864

[post_author] => 9832

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 10:32:16

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-09 23:32:16

[post_content] => Family and friend carers are essential members of the care team who often provide invaluable medication management support to the people they care for.

[caption id="attachment_28875" align="alignright" width="300"] This article was sponsored and developed in collaboration with PSA and Carers NSW[/caption]

However, pharmacists may perceive medication errors or non-adherence as a carer’s inability to fulfil this role,1 instead of an opportunity for improving education and support. Ensuring that carers are identified by pharmacists as members of the patient’s care team, included in discussions about the patient’s care and supported to fulfil their role is key to ensuring quality use of medicines and optimal outcomes for patients and carers.

Across Australia, there are approximately 3 million carers who provide unpaid care or support to a family member or friend living with disability, mental illness, chronic or life-limiting illness, drug or alcohol dependency or who is ageing or frail.2 This includes at least 391,300 children and young people under 25 years of age.2 A carer may be a parent, partner, sibling, relative, child, friend or neighbour of the person requiring care. Carers come from all walks of life, and anyone can become a carer at any time.

Carers are diverse and each caring experience is different. Carers provide a wide range of supports to help the person they care for to remain living at home and in the community. They may also provide ongoing support for someone living temporarily or permanently in residential care. This support can include personal care, domestic assistance, support with navigating and coordinating health and disability services, emotional and social support, as well as assistance with communication, decision making and advocacy.3

Pharmacies are a common setting that carers visit with, or on behalf of, the person they care for. Carers may support with:

This article was sponsored and developed in collaboration with PSA and Carers NSW[/caption]

However, pharmacists may perceive medication errors or non-adherence as a carer’s inability to fulfil this role,1 instead of an opportunity for improving education and support. Ensuring that carers are identified by pharmacists as members of the patient’s care team, included in discussions about the patient’s care and supported to fulfil their role is key to ensuring quality use of medicines and optimal outcomes for patients and carers.

Across Australia, there are approximately 3 million carers who provide unpaid care or support to a family member or friend living with disability, mental illness, chronic or life-limiting illness, drug or alcohol dependency or who is ageing or frail.2 This includes at least 391,300 children and young people under 25 years of age.2 A carer may be a parent, partner, sibling, relative, child, friend or neighbour of the person requiring care. Carers come from all walks of life, and anyone can become a carer at any time.

Carers are diverse and each caring experience is different. Carers provide a wide range of supports to help the person they care for to remain living at home and in the community. They may also provide ongoing support for someone living temporarily or permanently in residential care. This support can include personal care, domestic assistance, support with navigating and coordinating health and disability services, emotional and social support, as well as assistance with communication, decision making and advocacy.3

Pharmacies are a common setting that carers visit with, or on behalf of, the person they care for. Carers may support with:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28858

[post_author] => 7616

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 09:21:35

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-09 22:21:35

[post_content] => Food can act as a prompt for medicine administration and be an easy way for patients to incorporate doses into their routines.

Explaining to patients that they should take a medicine on an empty stomach or in a specific way away from food may not always be met with great enthusiasm! Confusion, and not fitting into a patient’s routine where possible, can lead to poor adherence and negative patient outcomes.

Why does food sometimes matter?

Food, or the absence of it, may significantly impact systemic exposure, safety, tolerability and effectiveness of a medicine, depending on its pharmacokinetics and adverse effects.

Take alendronate for example – the product information (PI) recommends taking it at least 30 minutes before the first food of the day as its bioavailability is negligible when taken with or up to 2 hours after a meal.1,2

Why do some PIs have a differing definition of an ‘empty stomach’?

This may stem from Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance in America, where many medicines are first introduced to the market.

FDA guidance for medicine sponsors suggests that if a medicine needs to be taken in fasted conditions, studies using an overnight fast of at least 10 hours before medicine administration, and waiting at least 4 hours after the dose before eating, are optimal. However, this might not be practical for all medicines and patients. It is then up to the medicine’s sponsor to provide pharmacokinetic data to support pragmatic and realistic dosing instructions for patients to separate food and medicine administration. Sponsors can use modified fasting conditions with differing separation times, and must consider frequency of medicine dosing, the likely demographics of the patient, the condition being treated and any other relevant factors.3 These could vary significantly between different medicines!

Why does CAL 3b say something different to the PI?

The Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook (APF) considers that an empty stomach for the purposes of medicine absorption is ‘at least half an hour before food or two hours after food’, as reflected in the wording of Cautionary Advisory Label (CAL) 3b.4,5

This standardised approach is to ensure medicine instructions are simplified and practical for patients, and may differ from the medicine’s PI. Remember, CALs are intended to be used as an adjunct, not a replacement, to verbal counselling.5

Consider adherence and use professional judgement when providing advice on dose administration.

This may require weighing up optimal dose timing and adherence if a patient can’t easily accommodate the timing of doses, particularly when treating chronic conditions.4

References

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Fosamax Plus Product Information. 2024. At: www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/136846

- Alendronate. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference; [updated 30 Oct 2024]. At: www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/martindale/22524-r?hspl=alendronate#content%2Fmartindale%2F22524-r%2319721-a3-v

- US Food and Drug Administration. Assessing the effects of food on drugs in INDs and NDAs – clinical pharmacology considerations: guidance for industry. 2022. At: www.fda.gov/media/121313/download

- Grannell, L. When should I take my medicines? Aust Prescr 2019;42:86–9.

- Sansom LN, ed. Cautionary advisory labels Explanatory notes. Australian pharmaceutical formulary and handbook; [updated 2024 Jul 24]. At: https://apf.psa.org.au/dispensing-and-labelling/cautionary-advisory-labels/explanatory-notes

[post_title] => What is an empty stomach?

[post_excerpt] => Confusion around what's meant by an empty stomach can lead to poor adherence. Here's how clear instructions can make a world of difference.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => what-is-an-empty-stomach

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-03-10 09:24:03

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-09 22:24:03

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28858

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => What is an empty stomach?

[title] => What is an empty stomach?

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/what-is-an-empty-stomach/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28860

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28830

[post_author] => 8304

[post_date] => 2025-03-05 12:47:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-05 01:47:11

[post_content] => Rosuvastatin. Pantoprazole. Perindopril. Sertraline. These were some of the most commonly prescribed PBS drugs in 2024. But what else do they have in common?

Tongue-twisters aside, they’re all examples of judiciously crafted drug names that have gone through countless rounds of testing by researchers, developers and brand marketing teams before making their way into Australian pharmacies.

Pharmacists are trained to interpret the class of drugs from the last few letters of a generic name, particularly after Australia transitioned to active ingredient prescribing in 2021. But how do we get from sertraline to Zoloft, and what about the many forms of ethinylestradiol-based birth contraceptives (Yaz, Jolessa… Sronyx)? As it turns out, drug naming is more complex than it seems.

Australian Pharmacist looks at the hard and fast rules governing drug monikers – all designed with patient safety in mind.

Breaking down a drug name

Pharmacists are likely well aware of the multiple guises medications take – three in fact: their chemical name, generic name (or nonproprietary), and brand name.

The chemical name follows rules set by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

Once the drug is approved by the relevant regulator, it’s then assigned a generic and brand name. The generic name is based on the active ingredient and follows a standardised nomenclature, while the brand name is the trademarked name proposed by the manufacturer.

It’s within these last two categories that drug developers have a bit of scope for creativity.

The science behind generic names

Before paracetamol lands in the pharmacy aisle as Panadol, pharmaceutical companies must first propose a generic name for the medication.

This name must be greenlit by two organisations: the national regulating body (i.e. in Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Association), and on a global stage, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Nonproprietary Name (INN) Programme.

Generic names follow an internationally recognised formula of prefix–infix–stem to maintain consistency regardless of where someone is located, and minimise the risk of prescribing errors. The:

| Stem | Uses | Examples |

| -cillin | Antibiotics (penicillin type) | Amoxicillin, ampicillin, |

| -mab | Monoclonal antibodies used for cancer, autoimmune diseases and other conditions | Adalimumab, abciximab, trastuzumab |

| -profen | Anti-inflammatories (ibuprofen type) | Ibuprofen, flurbiprofen |

| -vastatin | HMG-CoA inhibitors, lowers cholesterol | Atorvastatin, lovastatin, rosuvastatin |

| -vir | Anti-viral drugs (to treat HIV, herpes, hepatitis) | Aciclovir, ritonavir |

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28898

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-12 14:26:24

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-12 03:26:24

[post_content] => The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) issued an alert over the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used to treat infections such as urinary tract, respiratory and gastrointestinal infections.

What class of antibiotics prompted the alert?

Antimicrobials from the broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and moxifloxacin. This includes all oral and injectable forms of fluoroquinolones.

What are the documented adverse effects?

Central nervous system (CNS) and psychiatric events. Although rare, the complications are serious – and are potentially disabling and irreversible.

Adverse events include:

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

For example, the boxed warning for ciprofloxacin will now state:

Serious disabling and potentially irreversible adverse reactions

Fluoroquinolones, including ciprofloxacin, have been associated with disabling and potentially irreversible serious adverse reactions involving different body systems that have occurred together in the same patient. Patients of any age or without pre-existing risk factors have experienced these adverse reactions. These include but are not limited to serious adverse reactions involving the nervous system (see section 4.4 Effects on the CNS), musculoskeletal system (see section 4.4 Tendonitis and tendon rupture) and psychiatric effects (see section 4.4 Psychiatric reactions).

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28879

[post_author] => 3410

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 11:31:17

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-10 00:31:17

[post_content] => From guiding older patients on National Immunisation Program (NIP) stock to clarifying second-dose rules, here’s what pharmacists need to know about the 2025 influenza season.

1. Patients aged 65 years and older should wait for NIP stock to arrive

By this time of the year, most pharmacies will have ordered and received private stock of influenza vaccines. But for the 2025 season, deliveries of NIP are expected to commence around late March, following the confirmation of pre-allocated orders by pharmacies.

Older patients who present to the pharmacy requesting an influenza vaccine should be advised to wait until NIP stock arrives for optimum protection.

Patients who are 65 years and over should receive the NIP-funded Fluad Quad

0.50 mL vaccine or Fluzone High-Dose Quadrivalent, adjuvanted quadrivalent vaccines designed to boost the immune system's response to the vaccine.

These vaccines help to generate a stronger and more sustained antibody response, providing better protection against influenza and its complications in this vulnerable age cohort – reducing hospitalisations and severe outcomes from influenza.

2. Patients (mostly) only need one dose of an influenza vaccine

If a patient received an influenza vaccine earlier on in the season and is concerned about waning immunity – one vaccine is still enough. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to justify routinely administering a second influenza vaccine dose within the same season.

Optimal protection from the influenza vaccine persists for around 3–4 months after vaccination. While the vaccine’s effectiveness begins to wane after this point, most patients should be sufficiently protected throughout the season.

However, there are some exceptions. Patients eligible for a second dose include:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28864

[post_author] => 9832

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 10:32:16

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-09 23:32:16

[post_content] => Family and friend carers are essential members of the care team who often provide invaluable medication management support to the people they care for.

[caption id="attachment_28875" align="alignright" width="300"] This article was sponsored and developed in collaboration with PSA and Carers NSW[/caption]

However, pharmacists may perceive medication errors or non-adherence as a carer’s inability to fulfil this role,1 instead of an opportunity for improving education and support. Ensuring that carers are identified by pharmacists as members of the patient’s care team, included in discussions about the patient’s care and supported to fulfil their role is key to ensuring quality use of medicines and optimal outcomes for patients and carers.

Across Australia, there are approximately 3 million carers who provide unpaid care or support to a family member or friend living with disability, mental illness, chronic or life-limiting illness, drug or alcohol dependency or who is ageing or frail.2 This includes at least 391,300 children and young people under 25 years of age.2 A carer may be a parent, partner, sibling, relative, child, friend or neighbour of the person requiring care. Carers come from all walks of life, and anyone can become a carer at any time.

Carers are diverse and each caring experience is different. Carers provide a wide range of supports to help the person they care for to remain living at home and in the community. They may also provide ongoing support for someone living temporarily or permanently in residential care. This support can include personal care, domestic assistance, support with navigating and coordinating health and disability services, emotional and social support, as well as assistance with communication, decision making and advocacy.3

Pharmacies are a common setting that carers visit with, or on behalf of, the person they care for. Carers may support with:

This article was sponsored and developed in collaboration with PSA and Carers NSW[/caption]

However, pharmacists may perceive medication errors or non-adherence as a carer’s inability to fulfil this role,1 instead of an opportunity for improving education and support. Ensuring that carers are identified by pharmacists as members of the patient’s care team, included in discussions about the patient’s care and supported to fulfil their role is key to ensuring quality use of medicines and optimal outcomes for patients and carers.

Across Australia, there are approximately 3 million carers who provide unpaid care or support to a family member or friend living with disability, mental illness, chronic or life-limiting illness, drug or alcohol dependency or who is ageing or frail.2 This includes at least 391,300 children and young people under 25 years of age.2 A carer may be a parent, partner, sibling, relative, child, friend or neighbour of the person requiring care. Carers come from all walks of life, and anyone can become a carer at any time.

Carers are diverse and each caring experience is different. Carers provide a wide range of supports to help the person they care for to remain living at home and in the community. They may also provide ongoing support for someone living temporarily or permanently in residential care. This support can include personal care, domestic assistance, support with navigating and coordinating health and disability services, emotional and social support, as well as assistance with communication, decision making and advocacy.3

Pharmacies are a common setting that carers visit with, or on behalf of, the person they care for. Carers may support with:

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28858

[post_author] => 7616

[post_date] => 2025-03-10 09:21:35

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-09 22:21:35

[post_content] => Food can act as a prompt for medicine administration and be an easy way for patients to incorporate doses into their routines.

Explaining to patients that they should take a medicine on an empty stomach or in a specific way away from food may not always be met with great enthusiasm! Confusion, and not fitting into a patient’s routine where possible, can lead to poor adherence and negative patient outcomes.

Why does food sometimes matter?

Food, or the absence of it, may significantly impact systemic exposure, safety, tolerability and effectiveness of a medicine, depending on its pharmacokinetics and adverse effects.

Take alendronate for example – the product information (PI) recommends taking it at least 30 minutes before the first food of the day as its bioavailability is negligible when taken with or up to 2 hours after a meal.1,2

Why do some PIs have a differing definition of an ‘empty stomach’?

This may stem from Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance in America, where many medicines are first introduced to the market.

FDA guidance for medicine sponsors suggests that if a medicine needs to be taken in fasted conditions, studies using an overnight fast of at least 10 hours before medicine administration, and waiting at least 4 hours after the dose before eating, are optimal. However, this might not be practical for all medicines and patients. It is then up to the medicine’s sponsor to provide pharmacokinetic data to support pragmatic and realistic dosing instructions for patients to separate food and medicine administration. Sponsors can use modified fasting conditions with differing separation times, and must consider frequency of medicine dosing, the likely demographics of the patient, the condition being treated and any other relevant factors.3 These could vary significantly between different medicines!

Why does CAL 3b say something different to the PI?

The Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook (APF) considers that an empty stomach for the purposes of medicine absorption is ‘at least half an hour before food or two hours after food’, as reflected in the wording of Cautionary Advisory Label (CAL) 3b.4,5

This standardised approach is to ensure medicine instructions are simplified and practical for patients, and may differ from the medicine’s PI. Remember, CALs are intended to be used as an adjunct, not a replacement, to verbal counselling.5

Consider adherence and use professional judgement when providing advice on dose administration.

This may require weighing up optimal dose timing and adherence if a patient can’t easily accommodate the timing of doses, particularly when treating chronic conditions.4

References

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Fosamax Plus Product Information. 2024. At: www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/136846

- Alendronate. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference; [updated 30 Oct 2024]. At: www.medicinescomplete.com/#/content/martindale/22524-r?hspl=alendronate#content%2Fmartindale%2F22524-r%2319721-a3-v

- US Food and Drug Administration. Assessing the effects of food on drugs in INDs and NDAs – clinical pharmacology considerations: guidance for industry. 2022. At: www.fda.gov/media/121313/download

- Grannell, L. When should I take my medicines? Aust Prescr 2019;42:86–9.

- Sansom LN, ed. Cautionary advisory labels Explanatory notes. Australian pharmaceutical formulary and handbook; [updated 2024 Jul 24]. At: https://apf.psa.org.au/dispensing-and-labelling/cautionary-advisory-labels/explanatory-notes

[post_title] => What is an empty stomach?

[post_excerpt] => Confusion around what's meant by an empty stomach can lead to poor adherence. Here's how clear instructions can make a world of difference.

[post_status] => publish

[comment_status] => open

[ping_status] => open

[post_password] =>

[post_name] => what-is-an-empty-stomach

[to_ping] =>

[pinged] =>

[post_modified] => 2025-03-10 09:24:03

[post_modified_gmt] => 2025-03-09 22:24:03

[post_content_filtered] =>

[post_parent] => 0

[guid] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/?p=28858

[menu_order] => 0

[post_type] => post

[post_mime_type] =>

[comment_count] => 0

[filter] => raw

)

[title_attribute] => What is an empty stomach?

[title] => What is an empty stomach?

[href] => https://www.australianpharmacist.com.au/what-is-an-empty-stomach/

[module_atts:td_module:private] => Array

(

)

[td_review:protected] => Array

(

)

[is_review:protected] =>

[post_thumb_id:protected] => 28860

[authorType] =>

)

td_module_mega_menu Object

(

[post] => WP_Post Object

(

[ID] => 28830

[post_author] => 8304

[post_date] => 2025-03-05 12:47:11

[post_date_gmt] => 2025-03-05 01:47:11

[post_content] => Rosuvastatin. Pantoprazole. Perindopril. Sertraline. These were some of the most commonly prescribed PBS drugs in 2024. But what else do they have in common?

Tongue-twisters aside, they’re all examples of judiciously crafted drug names that have gone through countless rounds of testing by researchers, developers and brand marketing teams before making their way into Australian pharmacies.

Pharmacists are trained to interpret the class of drugs from the last few letters of a generic name, particularly after Australia transitioned to active ingredient prescribing in 2021. But how do we get from sertraline to Zoloft, and what about the many forms of ethinylestradiol-based birth contraceptives (Yaz, Jolessa… Sronyx)? As it turns out, drug naming is more complex than it seems.

Australian Pharmacist looks at the hard and fast rules governing drug monikers – all designed with patient safety in mind.

Breaking down a drug name

Pharmacists are likely well aware of the multiple guises medications take – three in fact: their chemical name, generic name (or nonproprietary), and brand name.

The chemical name follows rules set by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

Once the drug is approved by the relevant regulator, it’s then assigned a generic and brand name. The generic name is based on the active ingredient and follows a standardised nomenclature, while the brand name is the trademarked name proposed by the manufacturer.

It’s within these last two categories that drug developers have a bit of scope for creativity.

The science behind generic names

Before paracetamol lands in the pharmacy aisle as Panadol, pharmaceutical companies must first propose a generic name for the medication.

This name must be greenlit by two organisations: the national regulating body (i.e. in Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Association), and on a global stage, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Nonproprietary Name (INN) Programme.

Generic names follow an internationally recognised formula of prefix–infix–stem to maintain consistency regardless of where someone is located, and minimise the risk of prescribing errors. The:

| Stem | Uses | Examples |

| -cillin | Antibiotics (penicillin type) | Amoxicillin, ampicillin, |

| -mab | Monoclonal antibodies used for cancer, autoimmune diseases and other conditions | Adalimumab, abciximab, trastuzumab |

| -profen | Anti-inflammatories (ibuprofen type) | Ibuprofen, flurbiprofen |

| -vastatin | HMG-CoA inhibitors, lowers cholesterol | Atorvastatin, lovastatin, rosuvastatin |

| -vir | Anti-viral drugs (to treat HIV, herpes, hepatitis) | Aciclovir, ritonavir |

Get your weekly dose of the news and research you need to help advance your practice.

Protected by Google reCAPTCHA v3.

Australian Pharmacist is the official journal for Pharmaceutical Society of Australia Ltd.